Over the years, we have built up an array of special online resources designed to assist with teaching the story of Gettysburg, but this summer, we’ve done some of our best work yet on this front. Our 2018 interns –Frank Kline, Becca Stout, and Cooper Wingert– have organized a series of fascinating posts that tackle less-familiar topics related to the 1863 battle, and the famous cemetery dedication which followed.

Teachers and students can now learn first-hand many of the tragic details about the so-called “slave hunt” that occurred during the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania in June 1863. Wingert provides links to diaries and other records that detail how the Army of Northern Virginia captured black residents in south-central Pennsylvania, treating them like fugitive slaves. One of the cases involved a free black man named Amos Barnes, who was actually later released from a Confederate prison in Richmond because of the intervention of two Dickinsonians. This summer, Wingert also wrote about the Confederate occupation and shelling of Carlisle in late June and early July, which was part of the famous 1863 campaign, but has mostly been forgotten because of the immense scale of the battle which followed at Gettysburg. Wingert actually wrote a book about the Confederate approach to Harrisburg a few years ago, but now he has curated several primary sources related to the campaign, included several that have never before been available online.

Our other interns focused on the story of the cemetery dedication in November 1863 and Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address. Kline organized an incredibly useful post detailing contemporary newspaper reaction to Lincoln’s remarks and subsequent recollected accounts about how the short speech was written and received. Kline’s work was inspired by Gabor Boritt’s thought-provoking study, The Gettysburg Gospel (2005). Many teachers too easily embrace myths about the Gettysburg Address –that it was written on the back of envelope, for example, or that it was poorly received at first– and this post offers a helpful corrective. Stout’s post also provides an important supplement, especially for classes or families that might be visiting the Soldiers’ National Cemetery themselves. Stout describes how a half a dozen black army veterans came to be buried in the Civil War section of the national cemetery at Gettysburg. The story is far more complicated than you might imagine, beginning with the sad revelation that even though the Battle of Gettysburg occurred seven months after the Emancipation Proclamation and Lincoln’s endorsement of black soldiers, Union commanders still excluded black men from combat roles in the 1863 fighting in Pennsylvania. That meant, at first, that the soldiers’ cemetery at Gettysburg was segregated, despite all of the hope of “a new birth of freedom.”

Other House Divided Project resources on Gettysburg

- Lincoln’s Gettysburg Addresses (2013) exhibit for Google Arts & Culture which tells the story of the five known copies of the speech in Lincoln’s own handwriting

- Gettysburg Virtual Tour (2013) video tour of the battlefield co-produced by the Gilder Lehrman Institute that includes 13 stops and one-hour total of material hosted by Mathew Pinsker

- Blog Divided posts (2007-2018) make sure to check out over two dozen posts on the battle, campaign and its aftermath at our main project blog site

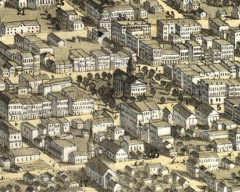

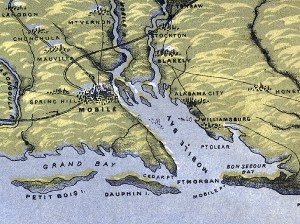

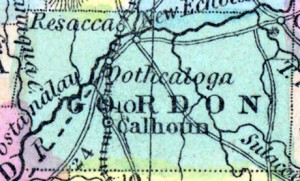

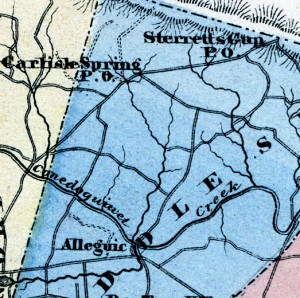

- Research engine records (2007-2018), our main research engine database contains over a thousand records related to Gettysburg, including some amazing zoomable maps

- Lincoln’s Writings (2015), our multi-media edition of Lincoln’s writings ranks the Gettysburg Address as the #1 most teachable Lincoln document –check out the array of resources on this page

- Confederate monument (2015) –Did you know there is a Confederate monument in Mechanicsburg, PA marking an element of the 1863 Confederate invasion? Check out this classroom-friendly discussion post to find out more.