The Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania in June 1863 had a profound effect on south central Pennsylvania’s African-American population. Numbering at least 5,000, local blacks fled the region in large numbers as the Confederate army drew near, and many of those who remained behind were quickly captured by Southern soldiers. [1]

Illustration of Confederate soldiers driving captured African-Americans during an earlier “slave hunt” in Maryland from 1862 (Harper’s Weekly, November 8, 1862)

This post explores the fate of several local blacks as they faced either captivity in Confederate prisons, or enslavement elsewhere in the South. But at least one captured black resident, a man named Amos Barnes, was returned to freedom by Confederate officials because of the intervention of a network of Dickinsonians.

On June 16, shortly after Confederate cavalry had occupied Chambersburg, the Southern horsemen were seen “scouring” the surrounding fields and countryside for not only horses, but African-Americans. “O! How it grated on our hearts to have to sit quietly & look at such brutal deeds,” wrote resident Rachel Cormany in her wartime diary. In Chambersburg alone, between 25-50 blacks were captured and shackled, many of them women and children. “I sat on the front step as they were driven by just like we would drive cattle,” recorded Cormany. [2] In nearby Mercersburg, Dr. Philip Schaff watched as a group of Confederate guerrillas, known as McNeill’s Rangers, “came to town on a regular slave-hunt, which presented the worst spectacle I ever saw in this war.” The Southerners threatened to “burn down every house which harbored a fugitive slave, and did not deliver him up within twenty minutes.” A subsequent search of the town turned up “several contrabands, among them a woman with two little children.” To Schaff, it was a “most pitiful sight, sufficient to settle the slavery question for every humane mind.” [3]

Locals were quick to note that many of the captured African-Americans were free-born Pennsylvanians and long-time members of the community. Jemima Cree, another Chambersburg woman, attempted to intercede on behalf of her free-born domestic servant, but was rebuffed by a Confederate officer, who claimed “he could do nothing, he was acting according to orders.” [4] Other residents took their complaints directly to Confederate generals, occasionally securing the release of a specific captive. [5] Chambersburg resident Jacob Hoke later wrote about how a connection to a Confederate officer helped secure the freedom of one African-American captive.

The story of one prisoner, Amos Barnes of Mercersburg, illustrates the confused and often protracted fate that awaited many African-Americans. Barnes claimed that he and another free African-American helped McNeill’s horsemen ferret out the location of runaway slaves. During the retreat, Barnes accompanied the Confederate army southward, under the “assurance” that he would be released and permitted to return home. However, at Martinsburg, Virginia (modern-day West Virginia), “in the confusion of such business,” he was sent along with other African-American captives to Castle Thunder Prison in Richmond. At first “confined closely in Castle Thunder,” Barnes was eventually put to work at nearby Camp Winder Hospital, and later “employed to labor on a boat carrying wood to Richmond.” He was allowed to keep “some refuse wood for himself and sell it in Richmond,” earning $25 in Confederate script. With those funds in hand, Barnes cajoled a Confederate guard to mail a letter on his behalf to acquaintances back in Mercersburg. [6]

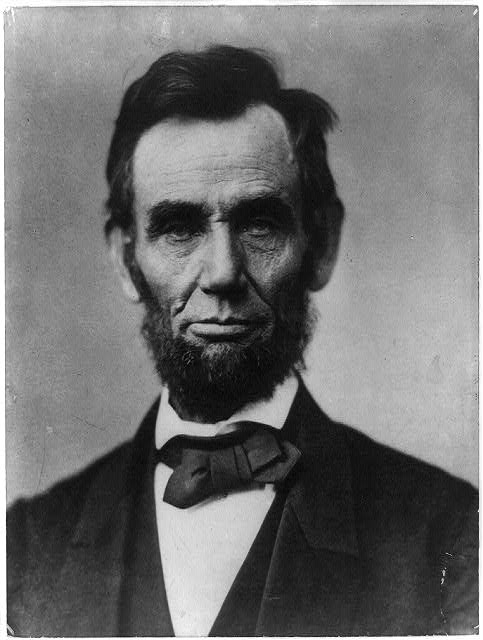

Rev. Thomas Creigh (Class of 1828) helped to secure the release of Amos Barnes. (House Divided Project, Dickinson College)

Barnes’s plea for help ultimately found its way into the hands of two Dickinsonians, who collaborated to secure his freedom. His letter first reached Rev. Thomas Creigh (Class of 1828) of Mercersburg, who wrote to another Dickinsonian, Rev. T.V. Moore (Class of 1838) of Richmond, asking Moore “to do something in their behalf to release them….” Moore paid a visit to Castle Thunder, and left convinced of Barnes’s freedom. He appealed to Confederate Assistant Secretary of War, John A. Campbell, who on December 14, 1863, ordered the release of “Amos Bar[n]es, a free negro from Pennsylvania… upon grounds which appear to the Department sufficient to justify an exceptional policy with regard to him.” [7]

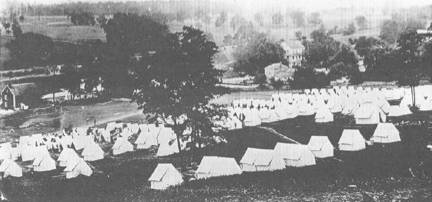

Barnes and Lewis were held at Castle Thunder Prison in Richmond. (Library of Congress).

Still, the strange story of Amos Barnes raises new questions. What were Confederates hoping to gain by imprisoning free African-Americans like Barnes? Southerners had long-held grievances about the flow of fugitive slaves into border states such as Pennsylvania, leading some historians to speculate that the “slave hunt,” was a reprisal. It appears some captured blacks were indeed enslaved. In a letter dated June 28, William S. Christian, an officer in the 55th Virginia, claimed to have been “offered my choice” of the captives, but declined “as I could not get them back home.” [8] Similarly, Lucy Buck, a Winchester, Virginia woman, recorded in her diary that her family’s fugitive slaves were captured near Greencastle and later recognized by a local Confederate cavalryman. Buck expected her family’s fugitives–a mother and her young children–to be returned to her family, while noting that male captives taken by the Confederate army “had all been sent to Richmond to work on fortifications.” [9]

Among those sent to Richmond were Barnes and another local black, Alexander Lewis of Chambersburg. Lewis was ultimately placed in charge of the culinary department at Castle Thunder, and his story survives in a collection of wartime stories of Chambersburg residents. An African-American child seized from York was also held at Castle Thunder, and tasked with carrying messages and performing errands. [10] Historian Mark Neely counts at least 16 free blacks from Pennsylvania who were held at Castle Thunder. In prison records, Confederate officials consistently distinguished these captives as “free negroes,” indicating an awareness of their legal status even as they were being detained. Neely argues that Confederates held these free African-Americans as “civilian political prisoners,” with the aim of exchanging them for Confederate civilians or fugitive slaves. More recent research by David Smith suggests that while Barnes was freed in December 1863, many African-Americans remained in Confederate prisons well into 1864, and perhaps beyond. Smith, drawing on Lucy Buck’s diary account and notes left by Confederate bureaucrats, concludes that captured African-Americans “had value to the Confederate hierarchy” as manual laborers. [11]

In the aftermath of Gettysburg, it was also apparent that some enslaved men from the Army of Northern Virginia had been left behind in Pennsylvania. A reporter for the New York Herald asserted that “among the rebel prisoners… were observed seven negroes in uniform and fully accoutered as soldiers.” In recent decades, these words have sometimes been seized upon as purported proof of the existence of Black Confederates. However, contrary to popular misconception, these seven men were among the estimated thousands of camp slaves who accompanied the Confederate army into Pennsylvania. While the Confederate force numbered around 75,000 fighting soldiers on the eve of Gettysburg, historians estimate that as many as 10,000 slaves marched north with the army. Non-combatants, these camp slaves filled important roles as officers’ servants, cooks and teamsters. According to Arthur Freemantle, a British observer traveling with Robert E. Lee’s army, “in rear of each regiment were from twenty to thirty negro slaves.” After the battle, many camp slaves were forced to tend to the wounded and dead. Elijah, the slave of Col. Issac E. Avery, recovered and buried his master’s body after Avery was mortally wounded on the slopes of Cemetery Hill.[12]

Primary Sources

Rachel Cormany’s June 16, 1863 diary entry.

Thomas Creigh’s June 26, 1863 diary entry.

Amos Stouffer’s June 19, 1863 diary entry.

William Heyser’s June 14, 18 and 22 diary entries.

Vermont Soldier Chester Leach’s July 15, 1863 letter from “Dear Wife”: The Civil War Letters of Chester K. Leach.

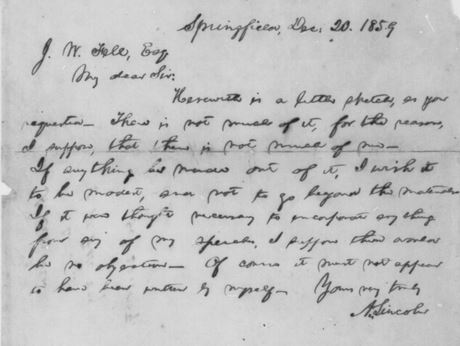

Amos Barnes was held at Castle Thunder Prison until December 1863. This notation by a Confederate clerk indicates that Barnes is to be exchanged under the next flag of truce. (Department of Henrico Papers, Section 11, Confederate Military Manuscripts Database).

Notes

[1] Joseph C.G. Kennedy, Population of the United States in 1860; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), 412, [WEB].

[2] Rachel Cormany, “Rachel Cormany Diary, 1863,” Valley of the Shadow Project, [WEB]; Franklin Repository, Chambersburg, PA, July 8, 1863, Valley of the Shadow Project, [WEB]; Jacob Hoke, The Great Invasion of 1863: Or, General Lee in Pennsylvania, (Dayton, OH: W. J. Shuey, 1887), 107-108, [WEB];

[3] Philip Schaff Diary, June 16-19, June 25-27, 1863, in The Woman’s Club of Mercersburg, Old Mercersburg, (New York The Frank Allaben Genealogical Company, 1912), 163-165, [WEB]; Ted Alexander, “‘A Regular Slave Hunt’: The Army of Northern Virginia and Black Civilians in the Gettysburg Campaign,” North & South 4, no. 7 (September 2001): 82–88, [WEB]; Steve French, Imboden’s Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign, (Hedgesville, WV: Steve French, 2008), 63-64, [WEB]; Captain John H. McNeill’s group of partisan rangers was temporarily attached to Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden’s command during the Gettysburg Campaign. See U.S. War Department. War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899), Series I, vol. 27, pt 2:291, [WEB].

[4] Jemima K. Cree, “Jenkins Raid,” in The Kittochtinny Historical Society: Papers Read before the Society from March, 1905 to February, 1908, (Chambersburg, PA: Repository Printing Press, 1908), 94, [WEB].

[5] Hoke, The Great Invasion, 107-108, [WEB]; Charles Hartman Diary, June 22, 1863, Philip Schaff Library, Lancaster Theological Seminary.

[6] “Discharged from Richmond,” Franklin Repository, December 23, 1863, Pennsylvania Civil War Newspapers Database; T.V. Moore to Isaac H. Carrington, November 1863, File 1025 C 1863, Letters Received by the Secretary of War, RG 109, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, National Archives and Records Administration.

[7] Thomas Creigh to T.V. Moore, November 10, 1863, Section 11, Confederate Military Manuscripts, Series A: C.S.A. Army, Department of Henrico Papers, 1861-1864, ProQuest History Vault Database; The Woman’s Club of Mercersburg, Old Mercersburg, 86, [WEB]; Official Records, Series II, 6:704-705, [WEB]; Peter C. Vermilyea, “The Effect of the Confederate Invasion of Pennsylvania on Gettysburg’s African-American Community,” Gettysburg Magazine, [WEB]; Mark E. Neely Jr. Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism, (University of Virginia Press, 1999), 201; James F. Epperson, “Lee’s Slave-Makers,” Civil War Times Illustrated 41, no. 4 (August 2002): 44; David G. Smith, On the Edge of Freedom: The Fugitive Slave Issue in South Central Pennsylvania, 1820-1870, (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013), 188-194; Edward L. Ayers, The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War and Emancipation in the Heart of America, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017), 45-49.

[8] “A Rebel Letter,” in Frank Moore (ed.), Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, 7:[WEB].

[9] Lucy Buck Diary, July 3, 1863, in Elizabeth R. Baer (ed.), Shadows on my Heart: The Civil War Diary of Lucy Rebecca Buck of Virginia, (Athens & London: The University of Georgia Press, 1997), 228.

[10] Jacob Hoke, Historical Reminiscences of the War; or Incidents which transpired in and about Chambersburg, during the War of the Rebellion, (Chambersburg, PA: M.A. Foltz, 1884), 144, [WEB].

[11] Neely, Southern Rights, 139-140; Smith, On the Edge of Freedom, 192-193; Creigh to Moore, November 10, 1863, Confederate Military Manuscripts, Series A: C.S.A. Army, Department of Henrico Papers, 1861-1864, ProQuest History Vault Database.

[12] “Incidents of the Battle,” New York Herald, July 11, 1863, [WEB]; Arthur Freemantle, Three Months in the Southern States, (New York: John Bradburn, 1864), 234, [WEB]. James M. Paradis, African Americans and the Gettysburg Campaign, (Toronto: The Scarecrow Press, 2013), 23-26, 72 [WEB].

For this post, I have assembled available digitized primary sources from the House Divided Project, the Dickinson College Archives, the Cumberland County Historical Society and from my book, The Confederate Approach on Harrisburg (2012). Featured below are accounts that describe a series of little-known skirmishes and events from the 1863 invasion, including the Confederate occupation of Carlisle. Of special interest are the stories of Samuel Hillman, a Dickinson professor who debated Confederate officers about slavery, and recollections from Dickinson alumni and Confederate officers Richard Beale and Richard Shreve who were among the Confederate troops responsible for shelling Carlisle on the evening of July 1-2. I created this post originally in the summer of 2018, but we will keep adding materials to it as they become available. Feel free to make your own suggestions or contributions using the comment box (“Leave A Reply”) below.

For this post, I have assembled available digitized primary sources from the House Divided Project, the Dickinson College Archives, the Cumberland County Historical Society and from my book, The Confederate Approach on Harrisburg (2012). Featured below are accounts that describe a series of little-known skirmishes and events from the 1863 invasion, including the Confederate occupation of Carlisle. Of special interest are the stories of Samuel Hillman, a Dickinson professor who debated Confederate officers about slavery, and recollections from Dickinson alumni and Confederate officers Richard Beale and Richard Shreve who were among the Confederate troops responsible for shelling Carlisle on the evening of July 1-2. I created this post originally in the summer of 2018, but we will keep adding materials to it as they become available. Feel free to make your own suggestions or contributions using the comment box (“Leave A Reply”) below.

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as