Contributing Editors for this page include Ana Kean and Leah Miller

Ranking

#47 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“That you should object to my adhering to a law, which you had assisted in making, and presenting to me, less than a month before, is odd enough. But this is a very small part.”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, September 22, 1861

The Lincoln Log, September 22, 1861

Close Readings

Ana Kean, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), October 2, 2013

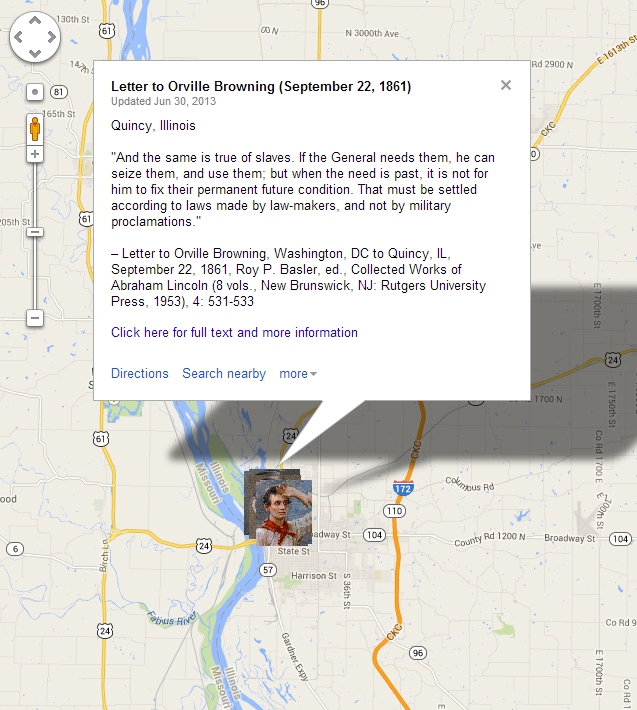

Custom Map

View in larger map

How Historians Interpret

Wrong in principle, Frémont ’s proclamation was ruinous in practice. ‘No doubt the thing was popular in some quarters,’ Lincoln told Browning, ‘and would have been more so if it had been a general declaration of emancipation. The Kentucky Legislature would not budge till that proclamation was modified; and Gen. Anderson telegraphed me that on the news of Gen. Frémont having actually issued deeds of manumission, a whole company of our Volunteers threw down their arms and disbanded. I was so assured, as to think it probable, that the very arms we had furnished Kentucky would be turned against us.’ The president hastened to add that Browning ‘must not understand I took my course on the proclamation because of Kentucky. I took the same ground in a private letter to General Frémont before I heard from Kentucky.'”

—Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript By Chapters, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 24 (PDF), pp. 2599-2600.

“Yet when Lincoln became president, he assured Southerners that he had no intention of interfering with slavery in their states. When the war broke out, he reassured loyal slaveholders on this score, and revoked orders by Union generals emancipating the slaves of Confederates in Missouri and in the South Atlantic states. This was a war for Union, not for liberty, said Lincoln over and over again—to Greeley in August 1862, for example: ‘If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it.’ In a letter to his old friend Senator Orville Browning of Illinois on September 22, 1861—ironically, exactly one year before issuing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation—Lincoln rebuked Browning for his support of General John C. Frémont’s order purporting to free the slaves of Confederates in Missouri. ‘You speak of it as being the only means of saving the government. On the contrary it is itself the surrender of government.’ If left standing, it would drive the border slave states into the Confederacy. ‘These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.’ To keep the border states—as well as Northern Democrats—in the coalition fighting to suppress the rebellion, Lincoln continued to resist antislavery pressures for an emancipation policy well into the second year of the war.”

—James M. McPherson, “The Hedgehog and the Foxes,” The Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 12, 1991.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

Private & confidential.

Executive Mansion, Washington

Sept 22d 1861.

My dear Sir,

Yours of the 17th is just received; and coming from you, I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering to a law, which you had assisted in making, and presenting to me, less than a month before, is odd enough. But this is a very small part. Genl. Fremont’s proclamation, as to confiscation of property, and the liberation of slaves, is purely political, and not within the range of military law, or necessity. If a commanding General finds a necessity to seize the farm of a private owner, for a pasture, an encampment, or a fortification, he has the right to do so, and to so hold it, as long as the necessity lasts; and this is within military law, because within military necessity. But to say the farm shall no longer belong to the owner, or his heirs forever; and this as well when the farm is not needed for military purposes as when it is, is purely political, without the savor of military law about it. And the same is true of slaves. If the General needs them, he can seize them, and use them; but when the need is past, it is not for him to fix their permanent future condition. That must be settled according to laws made by law-makers, and not by military proclamations. The proclamation in the point in question, is simply “dictatorship.” It assumes that the general may do anything he pleases—confiscate the lands and free the slaves of loyal people, as well as of disloyal ones. And going the whole figure I have no doubt would be more popular with some thoughtless people, than that which has been done! But I cannot assume this reckless position; nor allow others to assume it on my responsibility. You speak of it as being the only means of saving the government. On the contrary it is itself the surrender of the government. Can it be pretended that it is any longer the government of the U.S.—any government of Constitution and laws,—wherein a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation?

I do not say Congress might not with propriety pass a law, on the point, just such as General Fremont proclaimed. I do not say I might not, as a member of Congress, vote for it. What I object to, is, that I as President, shall expressly or impliedly seize and exercise the permanent legislative functions of the government.

So much as to principle. Now as to policy. No doubt the thing was popular in some quarters, and would have been more so if it had been a general declaration of emancipation. The Kentucky Legislature would not budge till that proclamation was modified; and Gen. Anderson telegraphed me that on the news of Gen. Fremont having actually issued deeds of manumission, a whole company of our Volunteers threw down their arms and disbanded. I was so assured, as to think it probable, that the very arms we had furnished Kentucky would be turned against us. I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol. On the contrary, if you will give up your restlessness for new positions, and back me manfully on the grounds upon which you and other kind friends gave me the election, and have approved in my public documents, we shall go through triumphantly.

You must not understand I took my course on the proclamation because of Kentucky. I took the same ground in a private letter to General Fremont before I heard from Kentucky.

You think I am inconsistent because I did not also forbid Gen. Fremont to shoot men under the proclamation. I understand that part to be within military law; but I also think, and so privately wrote Gen. Fremont, that it is impolitic in this, that our adversaries have the power, and will certainly exercise it, to shoot as many of our men as we shoot of theirs. I did not say this in the public letter, because it is a subject I prefer not to discuss in the hearing of our enemies.

There has been no thought of removing Gen. Fremont on any ground connected with his proclamation; and if there has been any wish for his removal on any ground, our mutual friend Sam. Glover can probably tell you what it was. I hope no real necessity for it exists on any ground.

Suppose you write to Hurlbut and get him to resign.

Your friend as ever

A. LINCOLN