The Battle of Milliken’s Bend took place on June 7, 1863 in Madison Parish, Louisiana and represented one of the most famous and courageous episodes for Black troops during the Civil War. While the opposition of Black troops in the Union Army persisted, the effort and bravery of the soldiers at Milliken’s Bend inspired the Union, beginning to convince the nation of the merit of Black troops and debunking the myth that Black soldiers would not fight.

The Battle of Milliken’s Bend took place on June 7, 1863 in Madison Parish, Louisiana and represented one of the most famous and courageous episodes for Black troops during the Civil War. While the opposition of Black troops in the Union Army persisted, the effort and bravery of the soldiers at Milliken’s Bend inspired the Union, beginning to convince the nation of the merit of Black troops and debunking the myth that Black soldiers would not fight.

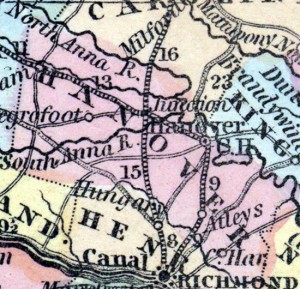

In order to boost the strength of his Army for an attack on the Confederate-controlled city of Vicksburg, Union General Ulysses S. Grant stripped his forts along the Mississippi river including the 150-yard wide Union camp Milliken’s Bend that laid fifteen feet above the right bank of the Mississippi. Of the 1410 soldiers left at Milliken’s Bend, 160 were whites, a part of the 23rd Iowa. The others were ex-slaves from Mississippi and Louisiana that were organized into three incomplete regiments, the 9th and 11th Louisiana and the 1st Mississippi.

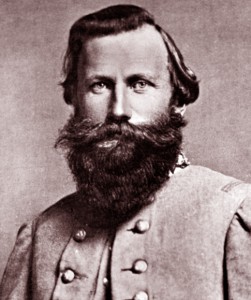

The Confederates launched an attack on Milliken’s Bend on the night of June 6 led by Confederate Brigadier General Henry E. McCulloch who planned to attack at night to avoid the heat and reduce the amount of assistance the fort’s defenders could receive from the Union gunboats. By 2:30 AM on June 7, the Confederate regiments encountered the Union pickets. With the order to withhold their fire until the Rebels were within musket-shot range, the battle turned into a bloody and scathing hand-to-hand fight noted as the longest bayonet-charge engagement of the war. By noon, the Federal warship Choctaw sent by Acting Rear Admiral David D. Porter turned the tide of battle firing shells on the Confederate Army causing the soldiers, already exhausted from the extreme heat to retreat.

The estimated casualties were high for the Black troops. Union Colonel Herman Lieb’s 9th Louisiana regiment sustained 66 killed and 62 mortally wounded, almost 45 percent of the entire regiment. Despite their losses, the greater significance of the battle lies with the effort and gallantry of the Black troops. Admiral Porter described the aftermath in a letter to General Grant, “The dead Negroes lined the ditch inside of the parapet or levee and were mostly shot on the top of the head. In front of them, close to the levee, lay an equal number of rebels, stinking in the sun.”

The Battle of Milliken’s Bend produced a change in army sentiment about Black troops that gradually echoed throughout the Union. Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana noted their accomplishment proclaiming, “The bravery of the blacks at Milliken’s Bend completely revolutionized the sentiment of the arm with regard to the employment of negro troops.” One of the most widespread testimonies on the battle was from Captain M.M. Miller, a white captain of the 9th Louisiana who commented, “I never more wish to hear the expression ‘the nigger won’t fight.” Come with me a 100 yards from where I sit and I can show you the wounds that cover the bodies of 16 as brave, loyal and patriotic soldiers as ever drew bead on a rebel.” Black historian W.E. DuBois eloquently described the transformation of the Black solider from slave to man:

“He was called a coward and a fool when he protected the women and children of his master. But when he rose and fought and killed, the whole nation proclaimed him a man and brother. Nothing else made emancipation possible in the United States. Nothing else made Negro citizenship conceivable, but the record of the Negro soldier as a fighter.”

A useful general interest website for teachers and students appears online at Milliken’s Bend: Honoring the Contributions of Black Soldiers in the Civil War (edited by Louis Elloie, Jr.)

One of the more complete descriptions of the battle can be found in Benjamin Quarles’ The Negro in the Civil War, one of the leading secondary sources on Black troops which is partially available of Google Books. Martha M. Bigelow’s article “The Significance of Milliken’s Bend in the Civil War” provides a good overview on the battle and highlights the significance of the Negro troops. For primary materials on the battle, teachers should utilize the Official Records, volume 24 for reports on the battle including ones from Union Admiral David Porter and Confederate General Henry E. McCulloch. Also available from the Library of Congress are the Papers of Cyrus Sears, 11th Louisiana.