Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities. Robert Latham (John Hawkes), Richard Schell (Tim Blake Nelson), and William N. Bilbo (James Spader) were three nineteenth-century political figures authorized by Secretary of State William Henry Seward in the winter of 1864-65 to help promote passage of what ultimately became the Thirteenth Amendment. Historians typically describe these men as the “Seward Lobby” but disagree over exactly how they lobbied for the amendment and to what degree President Lincoln was involved with or aware of their activities. The most in-depth study of the lobbying effort appeared in 1963 and is available in full-text at the Internet Archive. See especially the first chapter (“The Seward Lobby and the Thirteenth Amendment”) in LaWanda and John H. Cox, Politics, Principle, & Prejudice, 1865-66 (1963).

Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities. Robert Latham (John Hawkes), Richard Schell (Tim Blake Nelson), and William N. Bilbo (James Spader) were three nineteenth-century political figures authorized by Secretary of State William Henry Seward in the winter of 1864-65 to help promote passage of what ultimately became the Thirteenth Amendment. Historians typically describe these men as the “Seward Lobby” but disagree over exactly how they lobbied for the amendment and to what degree President Lincoln was involved with or aware of their activities. The most in-depth study of the lobbying effort appeared in 1963 and is available in full-text at the Internet Archive. See especially the first chapter (“The Seward Lobby and the Thirteenth Amendment”) in LaWanda and John H. Cox, Politics, Principle, & Prejudice, 1865-66 (1963).

What you will discover by reading this remarkable account is that Latham and Schell were in fact old friends of Seward’s and that Bilbo (James Spader) was a prominent southern attorney and businessman who had switched sides during the war and who was “known for his elaborate waistcoats, his long sideburns, and his elegant manners” (Cox and Cox, p. 6). Bilbo was prominent enough that he actually met with President Lincoln just after the 1864 election and corresponded with him later. Yet the movie introduces these characters as seedy outsiders, completely unknown to the president and forced to rent rooms in a “squirrel-infested attic,” as James Spader puts it memorably (Scene 10), because Seward was keeping them on such a tight retainer. That might be how lobbyists work today –on retainer and often in secret– but it wasn’t quite true then. After passage of the amendment, Latham, a major Wall Street investor (who later went bankrupt following the Panic of 1873), replied indignantly to an attempt by Seward to reimburse the men for their expenses. He wrote in a letter to Seward’s son Frederick, “A Gentleman called to have me give an acct of expenses. Which amt to nothing,” adding, “At any time that I can be of service to the Hon Sec of State or yourself I will do all I can but at my own expence,” (Cox and Cox, p. 24).

Yet the Spielberg movie portrays the men in much different light –as rough, political guns-for-hire who curse freely (Bilbo / Spader even says directly to President Lincoln at one point, “Well, I’ll be fucked.”) and who spread bribes easily. The movie makers invent a series of quick scenes involving fictional congressmen and the bribes that it takes to sway them. The most notable example of this corruption involves Rep. Clay Hawkins of Ohio (Walton Goggins) who Bilbo / Spader initially switched with the promise of a postmastership in Millersburg, Ohio. The movie actually has President Lincoln himself commenting cynically on this news by remarking, “He’s selling himself cheap, ain’t he?” (Scene 13). All of this is made up. There was a single lame duck Democratic congressman from Ohio who switched his vote in favor of the antislavery amendment in January 1865 but his name was Wells A. Hutchins and he did not receive any post-war patronage appointment in the federal government. Nor was he much recognizable in the character of Clay Hawkins. In real life, Hutchins was a reasonably tough, independent-minded Democrat who had voted to support the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia in 1862 and who had backed the Lincoln Administration on several controversial issues during the war, including the suspension of habeas corpus or civil liberties –an issue that was especially unpopular among Ohio Democrats. Understanding this background helps explain why he was a lame duck in 1865 and why he was a natural target for supporting the amendment. It had nothing to do with hunting, drinking or patronage.

Equally important from a strictly historical perspective, there’s no evidence connecting the Seward lobbyists to Hutchins or any Democrat outside of the eastern states. According to LaWanda and John Cox, the lobbyists, especially Bilbo, spent most of their time in New York (not Washington) generally attempting to persuade influential Democratic newspapers (such as the New YorkWorld) and the state’s Democratic governor (Horatio Seymour) to send signals that would allow wavering lame duck Democrats to feel more confident about switching their votes.

That is why in some ways the most telling example of “artistic license,” perhaps in the whole film, involves an amusing race between Bilbo / Spader and White House aide John Hay (Joseph Cross) during the day of the final House vote on January 31, 1865. The movie has the two men racing to get Lincoln’s response to reports of impending peace talks –a leak that threatens to jeopardize the entire lobbying effort. The younger Hay beats out the noticeably winded Bilbo, and then President Lincoln proceeds to draft an evasive reply that allows the final roll call to proceed and victory to be achieved. It is a dramatic climax with political machinations and social justice converging in ways that illustrate the film’s major insight about Lincoln –that he understood how a flawed, messy democratic process can be bent toward profoundly moral consequences. However, in real life, Bilbo was in New York at the time of the vote. There was actually an evasive message from the president but no footrace from the Capitol and no significant presence in Washington by the Seward lobbyists during the final fight to win House passage of the amendment.

(This post has been excerpted from a longer essay, “Warning: Artists at Work,” that appears in “The Unofficial Guide to Spielberg’s Lincoln” which is part of the House Divided Project’s new Emancipation Digital Classroom).

Images courtesy of Dreamworks

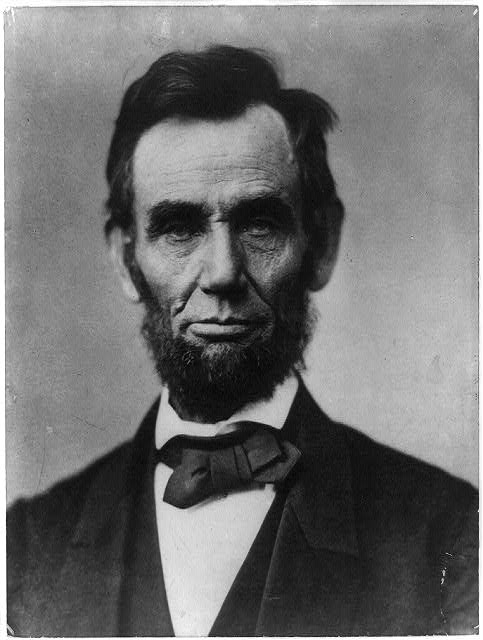

The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that

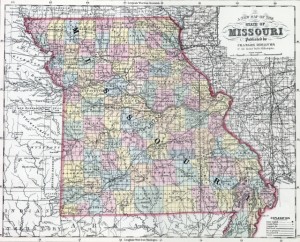

The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that  Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.

Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.