Exactly four years after he had surrendered Fort Sumter to the Confederates, Union officer Robert Anderson returned to Charleston to help once again raise the U.S. flag over the now-ruined harbor fortifications. Following an emotional mid-day ceremony, hundreds of men and women, included dozens of notable figures like abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, gathered on Friday afternoon, April 14, 1865 to hear the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher deliver a commemorative speech from what he memorably called, “this pulpit of broken stone.” Beecher spoke at length about the meaning of the war, offering President Lincoln in particular his “solemn congratulations” for his “disinterested wisdom” during the long conflict and for having maintained “his life and health under the unparalleled burdens and sufferings of four bloody years.” Yet that very night, of course, the president was shot at Ford’s Theatre. Lincoln died the next morning at almost exactly the same time that Garrison had gone with several of the other leading abolitionists to visit the gravesite of the late secessionist John C. Calhoun. The day before Beecher had vowed that “Slavery cannot come back.” Now, standing over Calhoun’s imposing tombstone, Garrison sternly echoed that sentiment by telling his friends: “Down into a deeper grave than this, slavery has gone, and for it there is no resurrection.”

Exactly four years after he had surrendered Fort Sumter to the Confederates, Union officer Robert Anderson returned to Charleston to help once again raise the U.S. flag over the now-ruined harbor fortifications. Following an emotional mid-day ceremony, hundreds of men and women, included dozens of notable figures like abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, gathered on Friday afternoon, April 14, 1865 to hear the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher deliver a commemorative speech from what he memorably called, “this pulpit of broken stone.” Beecher spoke at length about the meaning of the war, offering President Lincoln in particular his “solemn congratulations” for his “disinterested wisdom” during the long conflict and for having maintained “his life and health under the unparalleled burdens and sufferings of four bloody years.” Yet that very night, of course, the president was shot at Ford’s Theatre. Lincoln died the next morning at almost exactly the same time that Garrison had gone with several of the other leading abolitionists to visit the gravesite of the late secessionist John C. Calhoun. The day before Beecher had vowed that “Slavery cannot come back.” Now, standing over Calhoun’s imposing tombstone, Garrison sternly echoed that sentiment by telling his friends: “Down into a deeper grave than this, slavery has gone, and for it there is no resurrection.”

It was yet another one of those unforgettable moments from the American Civil War, and what makes it even more compelling is that we have some amazing photographic evidence of that astonishing trip. The War Department had sent several photographers to help capture scenes from the Sumter events and then from across the devastated city of Charleston. These are all now in the collection of the Library of Congress. Some of these images are famous, and widely reproduced, like the ones of the four black children (in Union military garb) seated by the pillars of the city’s well known circular church:

Other images from that period are less familiar, but still vital for understanding the narrative details of this critical episode. In particular, there is one heavily damaged image, not usually reproduced, but which shows a level of crowd detail from around Beecher’s speech unprecedented in the other images from the series.

Yet that heavily stained image (above), yields this wonderful detail (below), which clearly shows Major General Anderson, seated on the crowded platform itself, casually holding a walking stick, just to the right (our left) of the standing Rev. Beecher, who is tightly clutching the pages of his windblown speech.

Relying on this image and others from the series, we here at the House Divided Project have been busy trying to identify the rest of the notables at the event. Most important, we are trying to figure out exactly where editor William Lloyd Garrison was seated. His best modern biographer, the late Henry Mayer, used a detail from one of the blurrier versions of this image to claim that Garrison was probably the man in the big hat seated a few feet to Beecher’s left (our right), but the quality of this particular detail shows how unlikely that was.

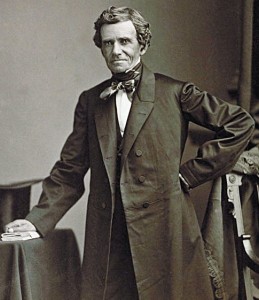

![1865-04-14 Garrison [?] at Sumter](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/1865-04-14-Garrison-at-Sumter-163x300.png) We think it is far more likely that Garrison was this lean, spectacled man, standing here (right) in reflective pose after the ceremony. In part, we believe this man was Garrison, because other images from the event suggest that he was seated behind Gen. Anderson, among other leading abolitionists, such as George Thompson, from Britain (and Garrison’s close friend), and also New York antislavery editor Theodore Tilton. White House aide John G. Nicolay, who was serving as the president’s personal emissary to the event, was also in that section of the platform. Details from some of these images are provided below. We also have some zoomable versions at the House Divided research engine, showing preparations, and two slightly different versions of Beecher’s speech, here and here. The bulk of the images from that journey have been digitized by the Library of Congress, more than two dozen of them are now available online. Check them all out and decide for yourself. If you come across anything important, please offer your insights in the comments section below. If you can, please help us identify any other notables in the audience. We are especially eager to find Robert Smalls, the ex-slave and wartime hero. Newspaper accounts claimed that the ceremony was attended by a mixed race crowd and that Smalls was present and widely celebrated –but we cannot find him, nor actually much evidence of any black presence near the speaker.

We think it is far more likely that Garrison was this lean, spectacled man, standing here (right) in reflective pose after the ceremony. In part, we believe this man was Garrison, because other images from the event suggest that he was seated behind Gen. Anderson, among other leading abolitionists, such as George Thompson, from Britain (and Garrison’s close friend), and also New York antislavery editor Theodore Tilton. White House aide John G. Nicolay, who was serving as the president’s personal emissary to the event, was also in that section of the platform. Details from some of these images are provided below. We also have some zoomable versions at the House Divided research engine, showing preparations, and two slightly different versions of Beecher’s speech, here and here. The bulk of the images from that journey have been digitized by the Library of Congress, more than two dozen of them are now available online. Check them all out and decide for yourself. If you come across anything important, please offer your insights in the comments section below. If you can, please help us identify any other notables in the audience. We are especially eager to find Robert Smalls, the ex-slave and wartime hero. Newspaper accounts claimed that the ceremony was attended by a mixed race crowd and that Smalls was present and widely celebrated –but we cannot find him, nor actually much evidence of any black presence near the speaker.

![Image 3 Garrison [?] standing center](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/Image-3-Garrison-standing-center-1024x638.png)

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

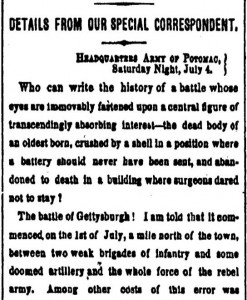

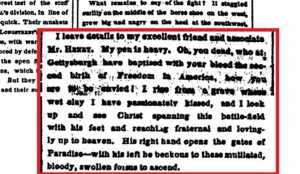

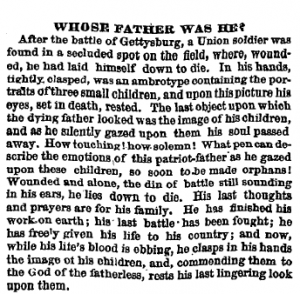

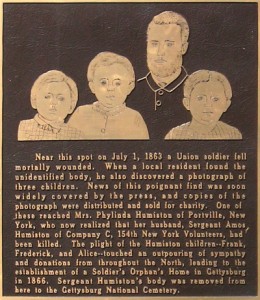

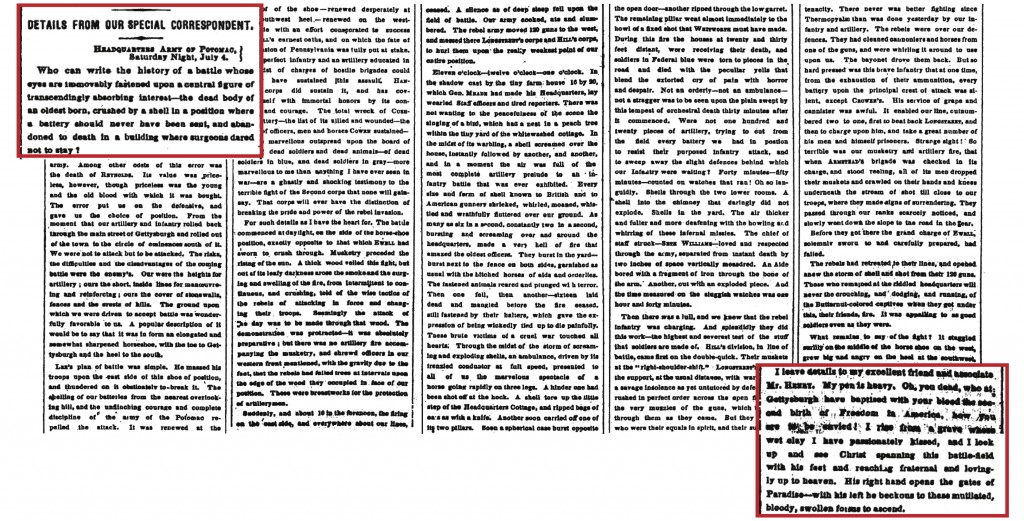

The story of the reporter,

The story of the reporter,

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.

One of the several critical strands in the “Lincoln” movie concerns the controversy surrounding the Hampton Roads peace talks (February 3, 1865), where President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward met with Confederate envoys Alexander Stephens, John Campbell and Robert M.T. Hunter for secret discussions about how to end the war on board the River Queen in Union-controlled Hampton Roads, Virginia (near Fortress Monroe). No transcript exists for their conversations that day. Lincoln and Seward died before leaving any recollection of the affair. So historians have mostly relied upon on the dubious

One of the several critical strands in the “Lincoln” movie concerns the controversy surrounding the Hampton Roads peace talks (February 3, 1865), where President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward met with Confederate envoys Alexander Stephens, John Campbell and Robert M.T. Hunter for secret discussions about how to end the war on board the River Queen in Union-controlled Hampton Roads, Virginia (near Fortress Monroe). No transcript exists for their conversations that day. Lincoln and Seward died before leaving any recollection of the affair. So historians have mostly relied upon on the dubious  According to the “Lincoln” movie script, Friday, January 27, 1865 was an action-packed and pivotal day. It was the day of Thaddeus Stevens’s controlled performance in the House, declaring himself strictly for “equality before the law.” It was also the day marked by Abraham Lincoln’s bitter argument with his oldest son Robert and then his subsequent clash with his wife Mary after he finally decided to concede to Robert’s desire to join the Union army. And it was in the evening of the 27th that both Mary Lincoln and later dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley urged the president to abandon his hidden-hand approach and provide more decisive leadership in the fight for the antislavery amendment. All of those “events” are fictional, but they are essential for understanding the film’s point-of-view –namely, that Lincoln interjected himself at the end of the battle for the constitutional amendment in a way that proved decisive.

According to the “Lincoln” movie script, Friday, January 27, 1865 was an action-packed and pivotal day. It was the day of Thaddeus Stevens’s controlled performance in the House, declaring himself strictly for “equality before the law.” It was also the day marked by Abraham Lincoln’s bitter argument with his oldest son Robert and then his subsequent clash with his wife Mary after he finally decided to concede to Robert’s desire to join the Union army. And it was in the evening of the 27th that both Mary Lincoln and later dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley urged the president to abandon his hidden-hand approach and provide more decisive leadership in the fight for the antislavery amendment. All of those “events” are fictional, but they are essential for understanding the film’s point-of-view –namely, that Lincoln interjected himself at the end of the battle for the constitutional amendment in a way that proved decisive. The filmmakers present this exchange in the most dramatic fashion possible, having Democratic leader Fernando Wood (D, NY) first disrupt the proceedings, allegedly waving “affidavits from loyal citizens” confirming the existence of secret peace talks. This creates chaos on the floor of the House that leads a fictional “conservative” Republican named Aaron Haddam to indicate (after receiving a critical nod from Preston Blair, perched in the gallery) that the “conservative faction of border and western Republicans” could not support an amendment “if a peace offer is being held hostage to its success.” Then there is a mad footrace from the Capitol to the White House, involving Lincoln’s aides and the Seward lobbyists. John Hay, the president’s young assistant private secretary, heatedly warns him against “making false representation” but Lincoln crafts his reply (technically true but obviously deceptive –since the commissioners were on their way to Hampton Roads, VA) and hands the note to seasoned lobbyist William N. Bilbo (James Spader). Bilbo then delivers it to Rep. Ashley who reads it with a flourish to the entire House. There is no record of any of this in the official proceedings. Nor does Ashley claim in his recollection that he read the note from the president on the House floor. Instead, it seems he may have simply showed it to some key figures. Bilbo was not even in Washington at the time (see previous post

The filmmakers present this exchange in the most dramatic fashion possible, having Democratic leader Fernando Wood (D, NY) first disrupt the proceedings, allegedly waving “affidavits from loyal citizens” confirming the existence of secret peace talks. This creates chaos on the floor of the House that leads a fictional “conservative” Republican named Aaron Haddam to indicate (after receiving a critical nod from Preston Blair, perched in the gallery) that the “conservative faction of border and western Republicans” could not support an amendment “if a peace offer is being held hostage to its success.” Then there is a mad footrace from the Capitol to the White House, involving Lincoln’s aides and the Seward lobbyists. John Hay, the president’s young assistant private secretary, heatedly warns him against “making false representation” but Lincoln crafts his reply (technically true but obviously deceptive –since the commissioners were on their way to Hampton Roads, VA) and hands the note to seasoned lobbyist William N. Bilbo (James Spader). Bilbo then delivers it to Rep. Ashley who reads it with a flourish to the entire House. There is no record of any of this in the official proceedings. Nor does Ashley claim in his recollection that he read the note from the president on the House floor. Instead, it seems he may have simply showed it to some key figures. Bilbo was not even in Washington at the time (see previous post  No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war.

No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war. Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in

Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in  In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.

In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.  Smith

Smith