Ranking

#8 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

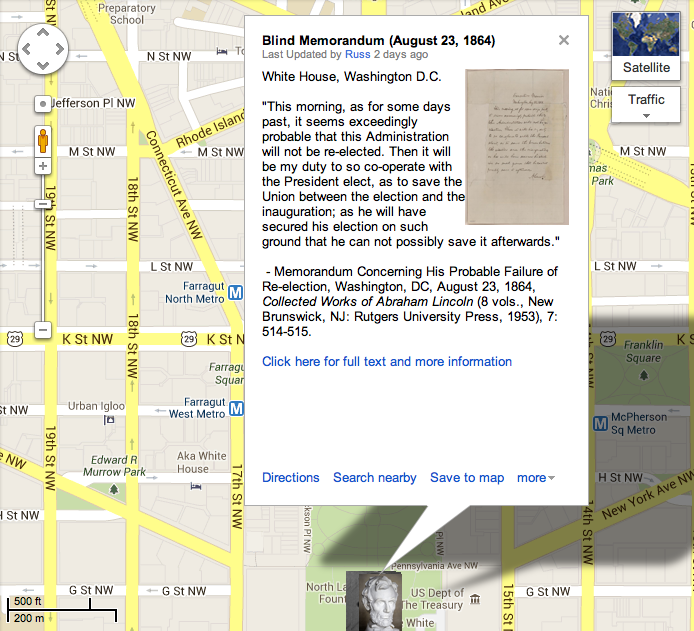

Annotated Transcript

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, August 23, 1864

Image Gallery

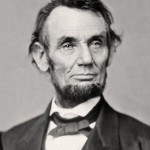

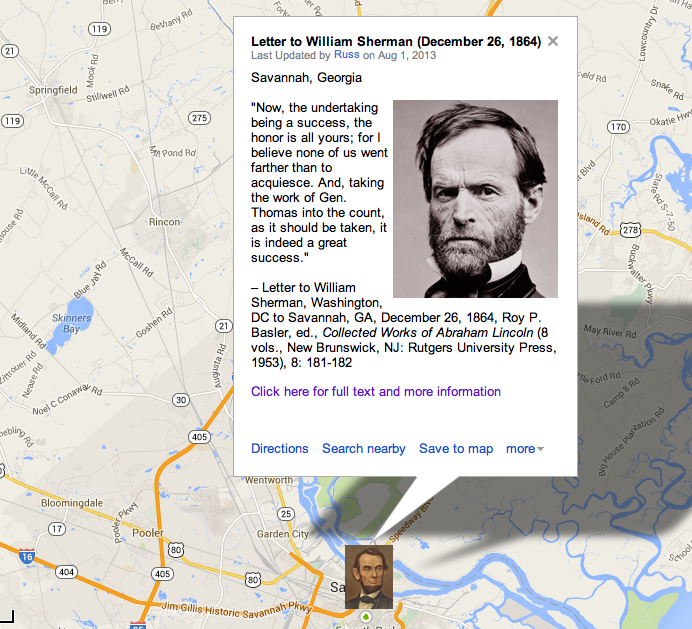

- Lincoln in 1864

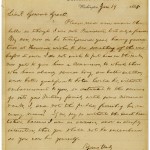

- Memo (front)

- Memo (reverse)

- Lincoln Cabinet, c. 1864

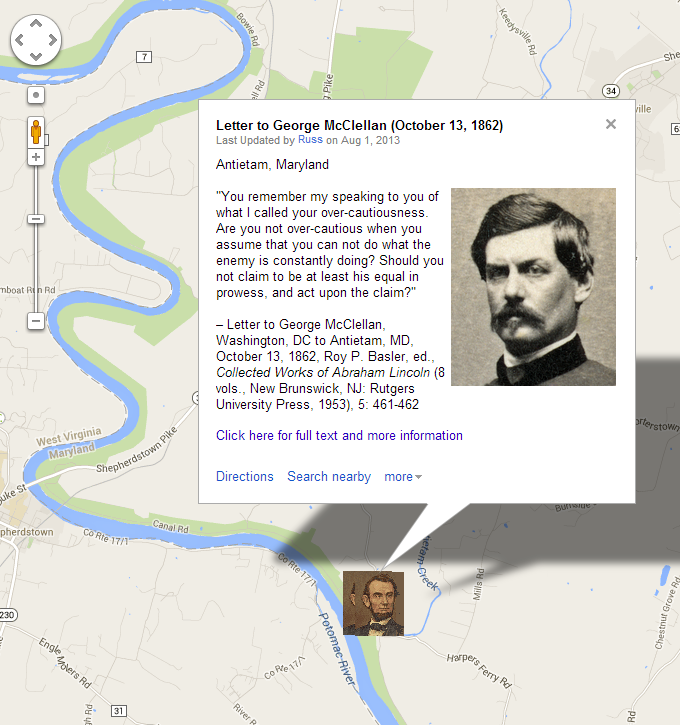

- George McClellan

- Lincoln & McClellan in 1862

Close Reading

Click here for the video transcript

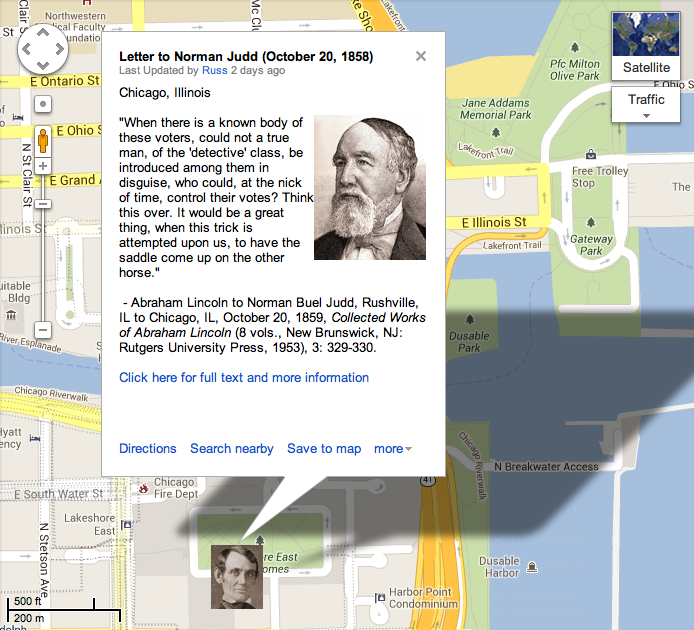

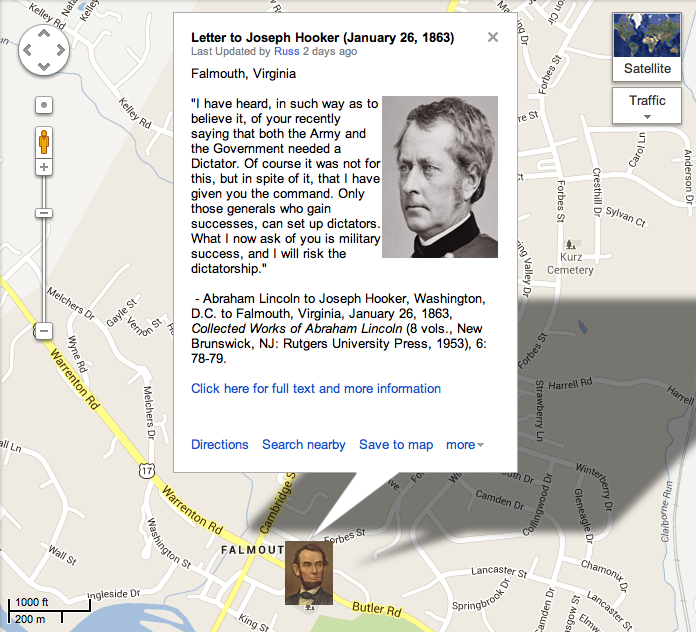

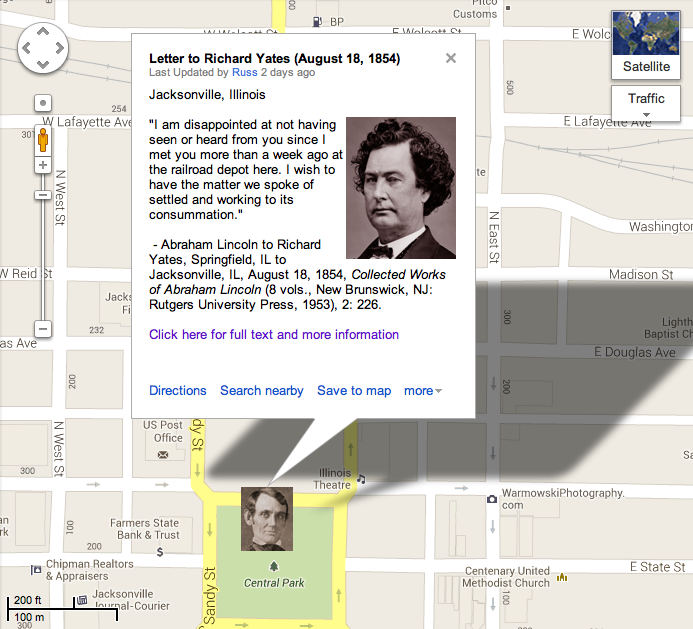

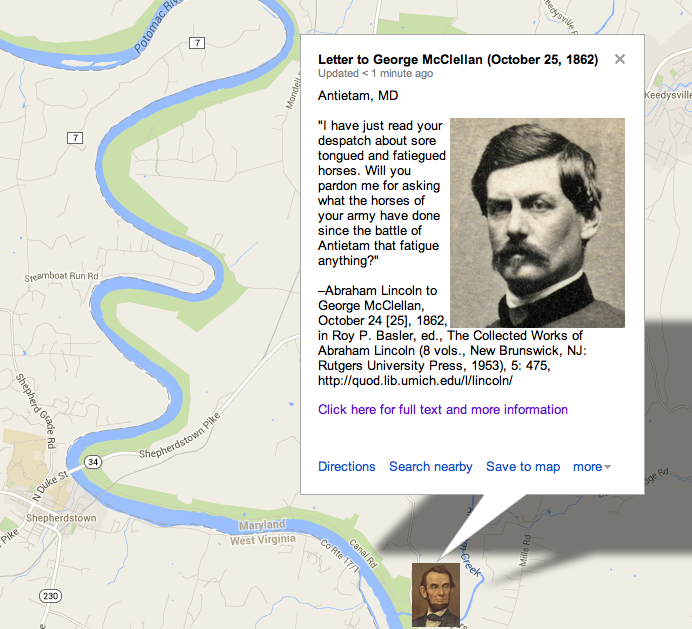

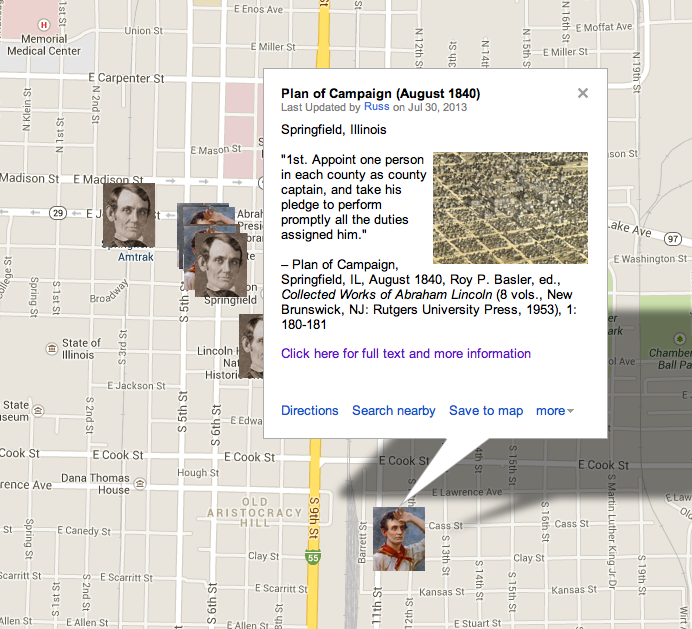

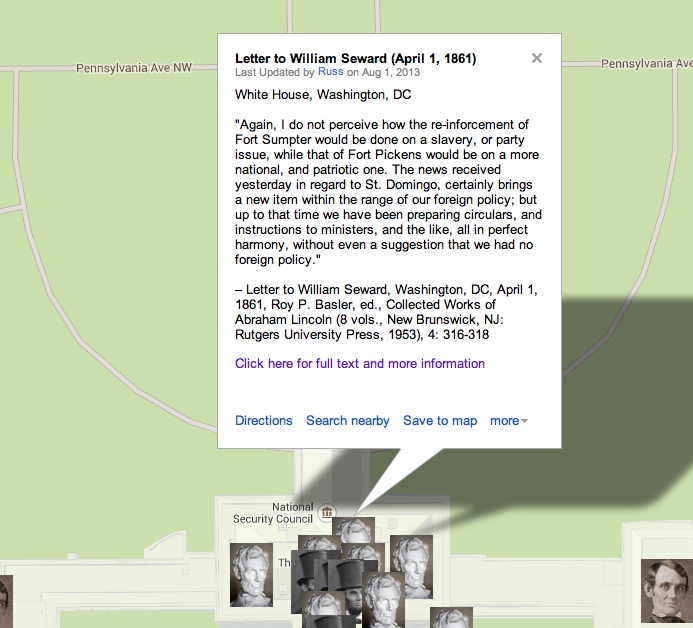

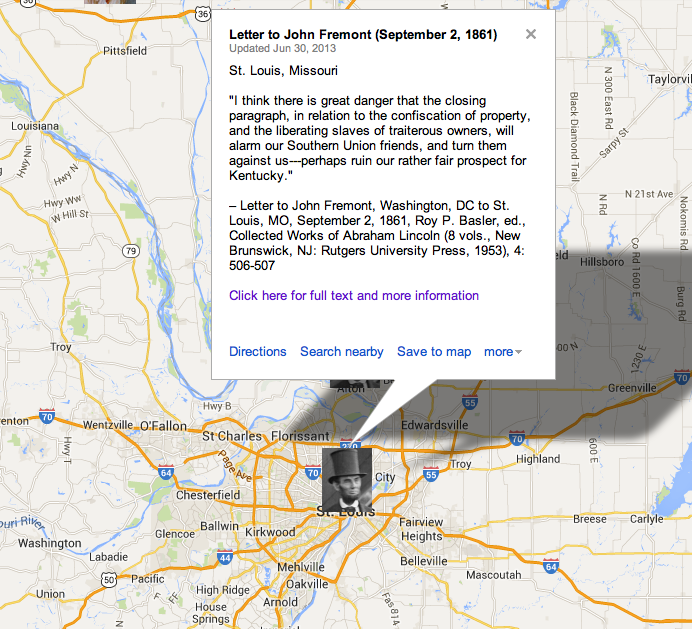

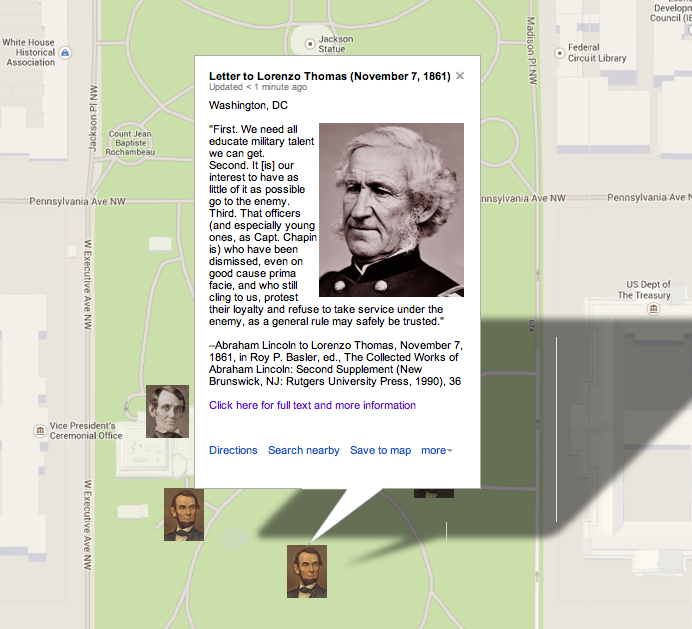

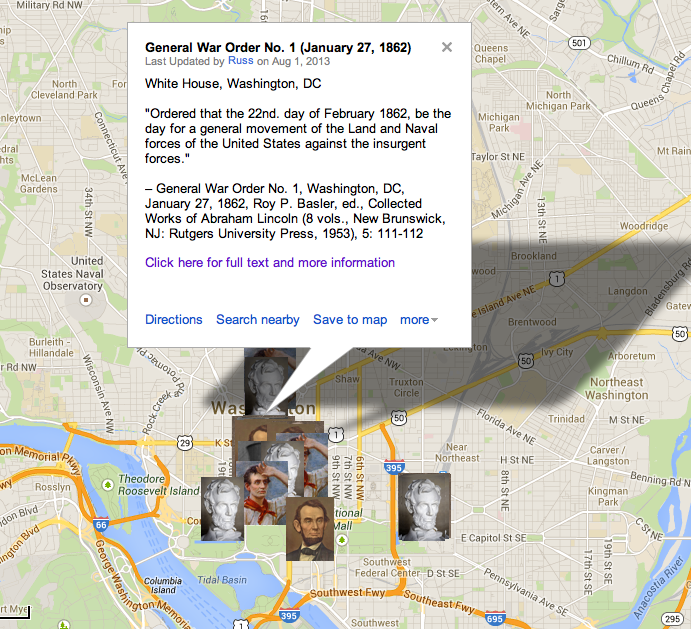

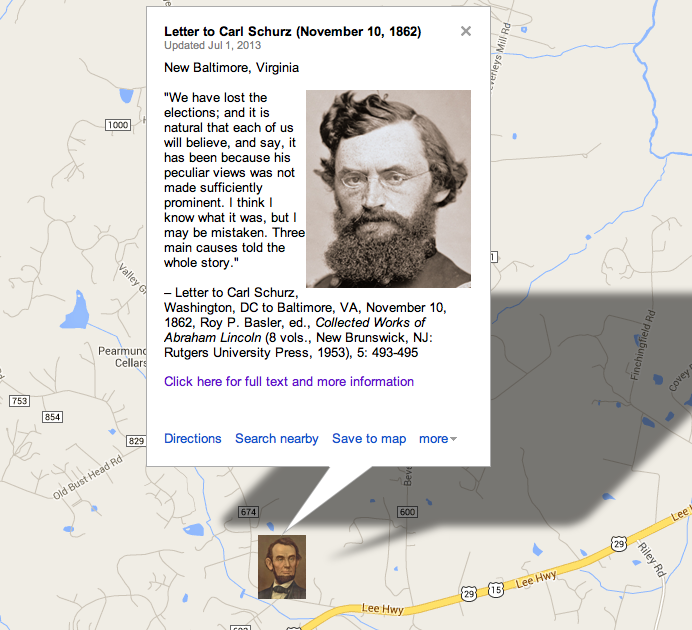

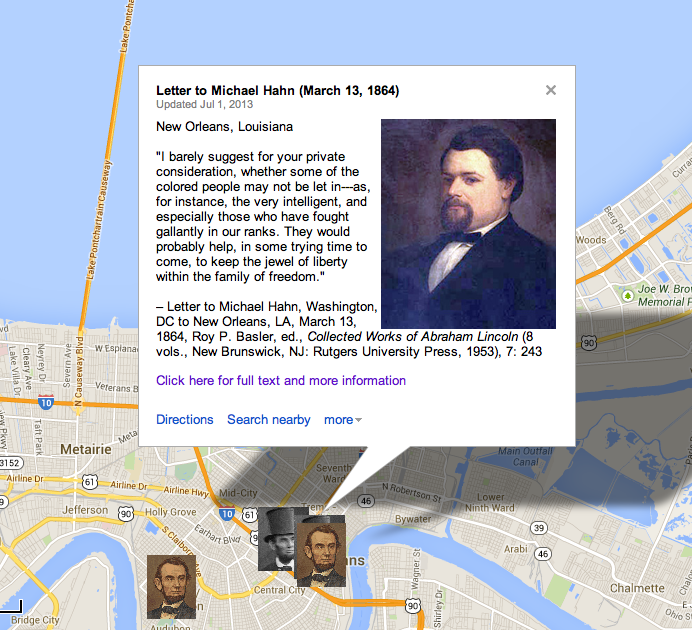

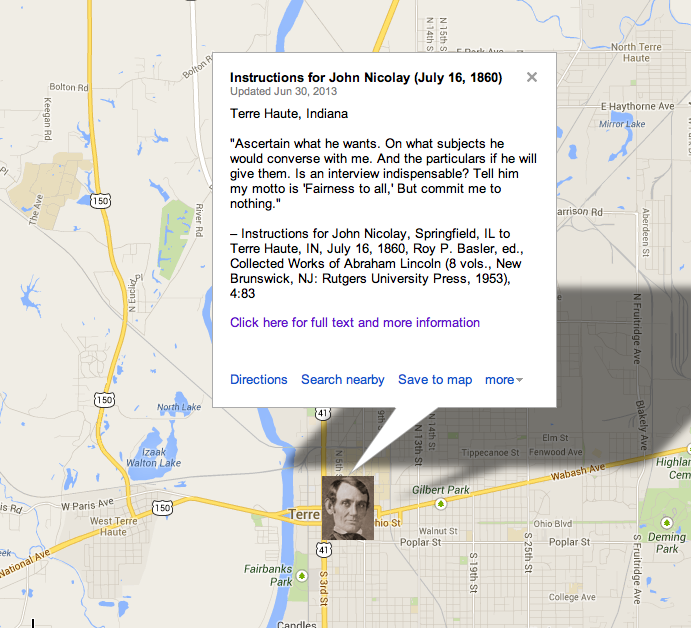

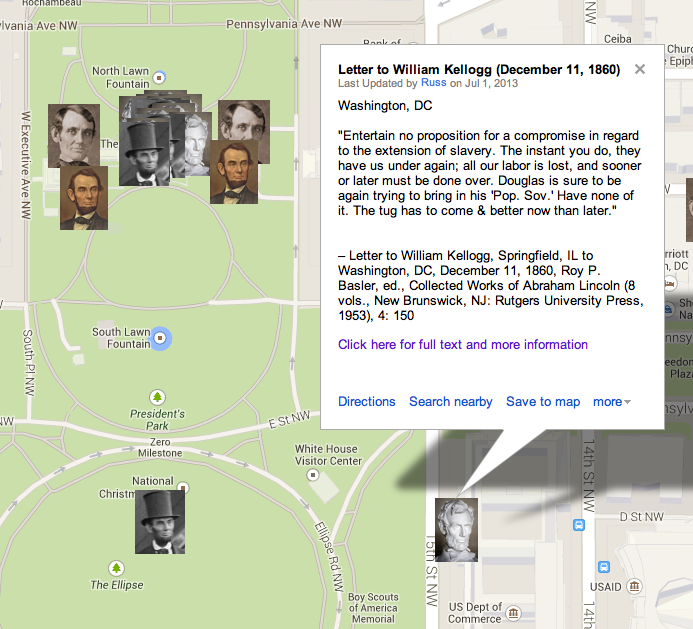

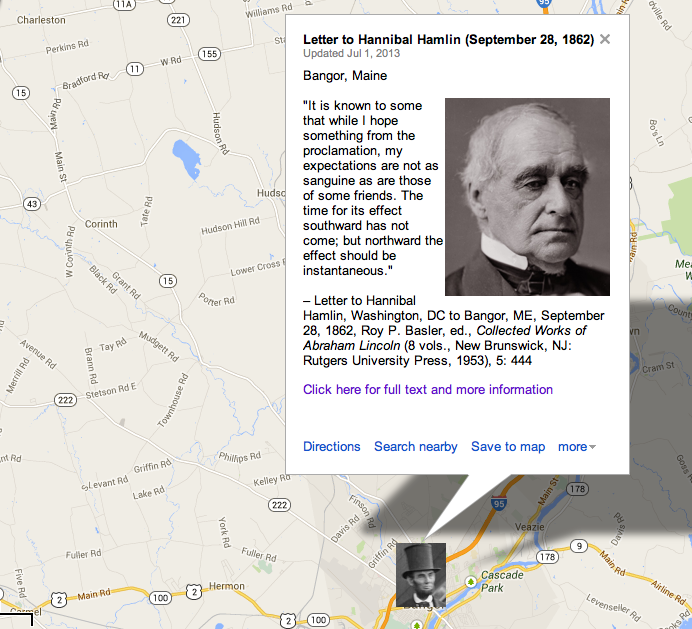

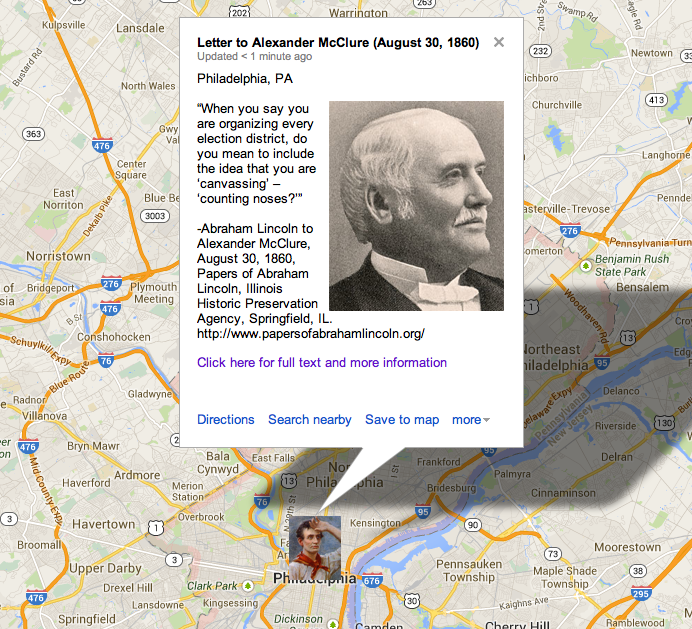

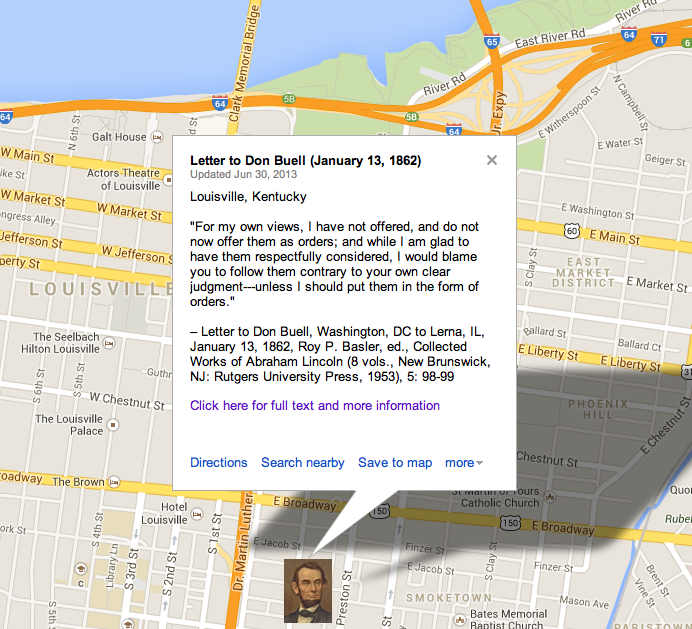

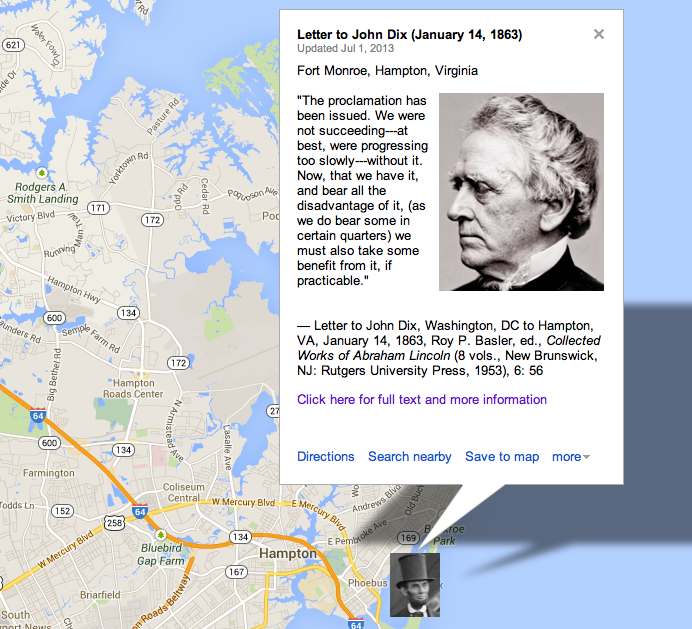

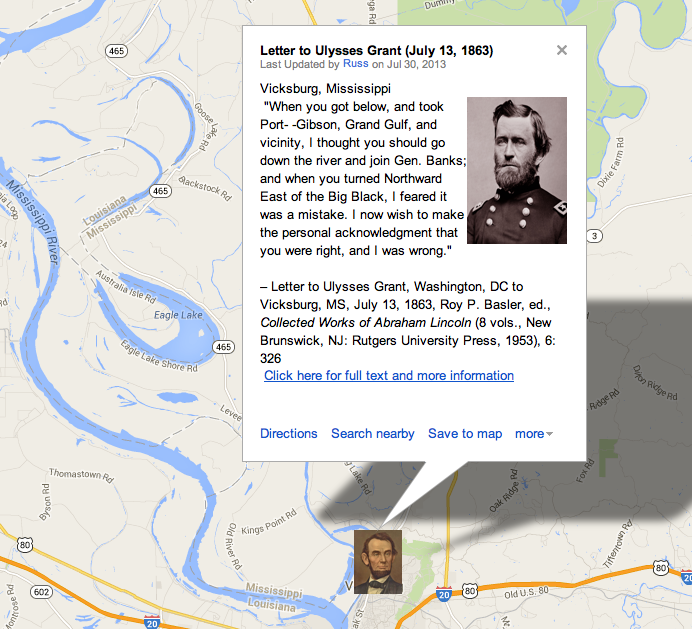

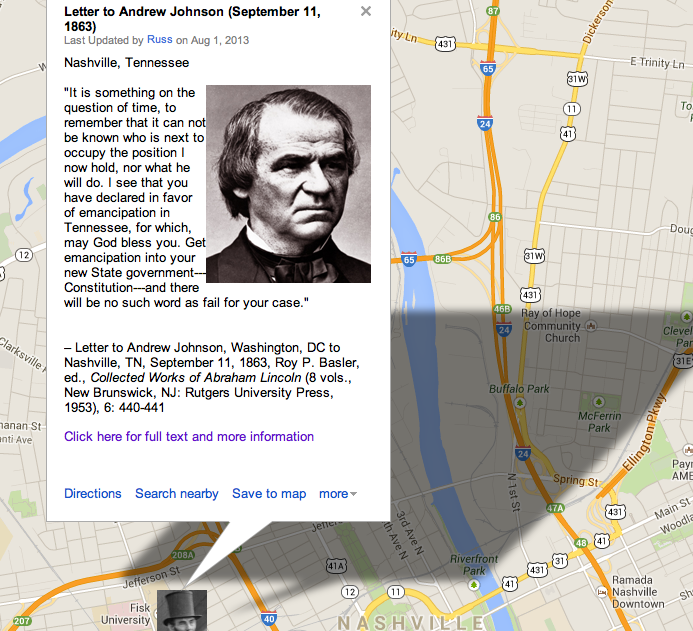

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Henry Raymond letter to Abraham Lincoln, August 22, 1864

Abraham Lincoln letter to Henry Raymond, August 24, 1864

John Hay diary, November 11, 1864

John Nicolay and John Hay recollection, Abraham Lincoln: A History, 1914

How Historians Interpret

“Lincoln’s language revealed not merely his pessimism about his own fortunes but his realistic understanding of the forces that opposed his reelection. He did not say that if he was defeated the country would fall into the hands of Copperheads who would consent to the division of the Union and the recognition of the Confederacy. He did not think the Democrats were disloyal. There had been ‘much impugning of motives, and much heated controversy as to the proper means and best mode of advancing the Union cause,’ he conceded, but he derived great satisfaction in recording that ‘a great majority of the opposing party’ was as firmly committed as the Republicans to maintaining the integrity of the Union, and he noted with pride that ‘no candidate for higher office whatever, high or low, has ventured to seek votes on the avowal that he was for giving up the Union.’ Nor did he have doubts about the loyalty of George B. McClellan, whose nomination by the Democrats he anticipated. But he did think that if the Democrats elected McClellan the party platform would force the new administration to seek an armistice, which virtually assured Confederate independence.”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 529

“Pressure was building on Lincoln to drop emancipation as a condition for peace and to negotiate an end to the war. The situation came to a head August 22, when the Republican National Committee met in New York. After the meeting, Raymond delivered the grim news to the president: If the election were held that day, he would lose the key states of New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. Indeed, he might lose every state. Raymond blamed Lincoln’s problems on military losses and the general belief ‘that we are not to have peace in any event under this Administration until Slavery is abandoned.’ Many Americans, he said, thought emancipation was all that was standing between them and peace. Raymond suggested that Lincoln show the country that Davis, not he, was the problem. Offer Davis peace ‘on the sole condition of acknowledging the supremacy of the constitution,’ he advised Lincoln. Davis would turn it down, insist on independence, and the country would see that he was the true obstructionist. Lincoln thought about the strategy and then adopted it. On August 24 he wrote a memo authorizing Raymond to meet with Davis and propose an immediate cease-fire based on the restoration of the Union only. All other questions, including emancipation, would be dealt with later. The problem was that this would send a terrible message to freedmen, especially those who were serving in the Union army. Almost exactly a year earlier, Lincoln had written a public letter in which he acknowledged the crucial role black soldiers were playing in the war. ‘If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept,’ he told his critics in August 1863. Three days before Raymond pitched his plan, Lincoln had sworn again he would not abandon the freedmen to sue for peace, saying that he would be ‘damned in time & in eternity’ if he did. Raymond’s plan was the primrose path. Confronted with Raymond’s message of political doom, Lincoln had to make the hardest decision of his political career: abandon emancipation and his own moral code or lose in November. Lincoln decided to risk the latter. In the words of his hero, Henry Clay, he would ‘rather be right than president.’ Within twenty-four hours of drafting the memo authorizing Raymond to meet with Davis, Lincoln changed his mind and rejected the idea. Sending a commission to Richmond would be worse than losing the Presidential contest—it would be ignominiously surrendering it in advance,’ he told Raymond. Lincoln now prepared to lose. He wrote a memo to his cabinet, sealed it in an envelope, and asked each of his cabinet members to sign the back of the envelope, contents unseen.”

Further Reading

For educators:

- Civil War Trust, Election of 1864 (Grades 9-12)

- NEH EDSITEment, Abraham Lincoln and Wartime Politics (Grades 9-12)

For everyone:

- Pinsker, Matthew. “Seeing Lincoln’s Blind Memorandum.” In Lincoln and Leadership: Military, Political and Religious Decision Making. Edited by Randall M. Miller. New York: Fordham University Press, 2012, pp. 60-77.

- Weber, Jennifer L. “Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 32 (Winter 2011), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0032.105

Searchable Text