Contributing Editors for this page include Andrew Villwock and Rhonda Webb

Ranking

#120 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, December 26, 1864

The Lincoln Log, December 26, 1864

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” participant Andrew Villwock, Fall 2013

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” participant Rhonda Webb, Fall 2013

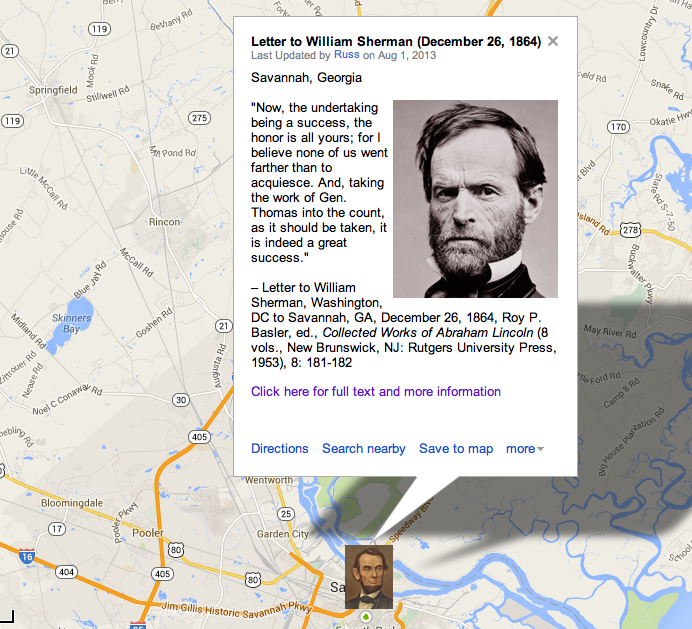

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“While Hood was marching to destruction in Tennessee, Sherman was moving across Georgia in the fabled march to the sea. He aimed to emerge at some point on the coast like Savannah or Port Royal where the Navy could pick him up and carry him to Virginia to join Grant in a final crushing movement against Lee. At first, Sherman himself was not sure which coastal port he would go to, and until he decided Lincoln and Grant knew only the general objective of his movement. Discussing Sherman with the General’s brother, a United States Senator, Lincoln said: ‘I know what hole he went in at, but I can’t tell what hole he will come out of.’ Although Sherman was virtually unopposed and untroubled by supply difficulties because he lived off the country, Lincoln feared for his safety. The President worried that the Confederates would concentrate enough forces to trap Sherman in the interior of Georgia. Grant assured Lincoln that Sherman had a large enough army to protect himself against any attack and, as Grant expressed it, strike bottom on salt water. By December 10, Sherman was in front of Savannah and laid the city under siege and certain capture. The Confederates evacuated it on the twenty-first, and Sherman had his base on the ocean. In a dramatic telegram to the government, he presented Savannah to the nation as a Christmas present. Lincoln was delighted with Sherman’s success and his despatch. He wrote the General a letter of appreciation which was, at the same time, an admirable analysis of the effect of Sherman’s movement on Southern morale.”

–T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952), 345

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln