Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

INTRODUCTION

Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784) was born in Africa, kidnapped and enslaved at the age of seven, and then forced into domestic service for the Boston family of John and Susanna Wheatley. During the 1760s and 1770s, Phillis Wheatley was enslaved in Boston but learned how to read and write, and proved to be a true prodigy as a poet. She began publishing poems in local newspapers in the late 1760s and became something of a celebrity by the early 1770s. Her first published collection of 28 poems, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) appeared in London and included “On Being Brought From Africa to America,” which is presented below and which many now regard as her most famous literary effort. Later, during the American Revolution, Wheatley also achieved additional fame for supporting the patriot cause and for praising George Washington in a poem, which she sent to him directly and which he acknowledged in correspondence. The Wheatley family had a complicated relationship with Phillis Peters (the name she took once she married John Peters, a free black Bostonian). The family, especially Susanna Wheatley, promoted the young black poet but kept her enslaved until they finally manumitted her in 1774. During her years in freedom, Phillis Peters continued to write poetry in Boston but often struggled with various financial and family difficulties such as losing multiple children to illness and enduring the absences of her husband. She died essentially alone in 1784 at the age of 31, but left behind a legacy of nearly 150 poems that helped define her age while challenging, however subtly, the paradox and injustice of slavery and racism that existed beside the American revolutionary ideals of natural rights and democracy.

SOURCE FORMAT: Poem

WORD COUNT: 58 words

RELATED TEXTS: Adams letters (1776) // Declaration (1776) // Equiano narrative (1789) // Harper poem (1858) // Popel poem (1934) // Gorman poem (2021)

CONTEXT LECTURE: Age of Enlightenment

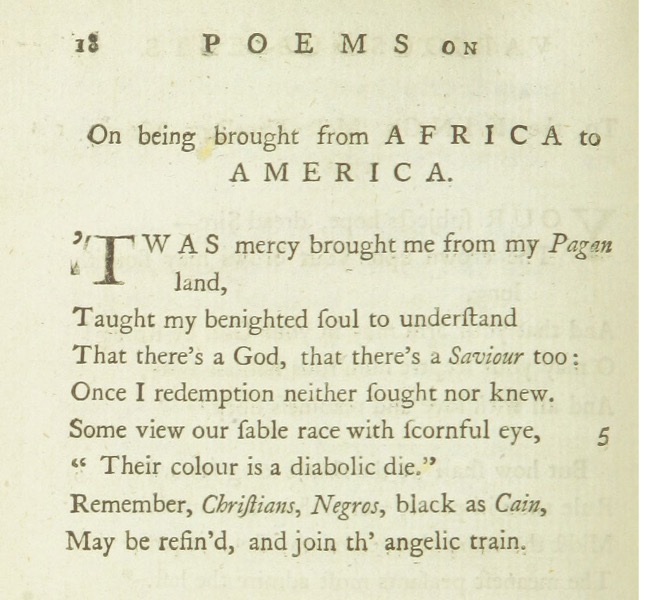

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

- Was Wheatley being sincere when she called her forced removal from Africa a form of “mercy”?

- Was Wheatley being intentionally subversive, or even confrontational, when she reminded “Christians” that African Americans might well “join th’ angelic train”?

- How might eighteenth-century white audiences have reacted to reading such a poem from an enslaved black woman?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents. —George Washington to Phillis Wheatley, 1776

CLASSROOM VIDEO:

Hannah Jewell, author of She Caused a Riot, discusses Wheatley

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Slave Voyages database

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Phillis Wheatley Poems (British Library)

- Phillis Wheatley’s poem on tyranny & slavery, 1772 (Gilder Lehrman Institute)

- Forgotten Founders: Phillis Wheatley (National Constitution Center)

- George Washington to Phillis Wheatley, February 28, 1776 (Founders Online)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Parker Hayes (Summer 2022)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Cameron Nye (Summer 2022)

- Handout –Wheatley