By Cameron Nye (Summer 2022)

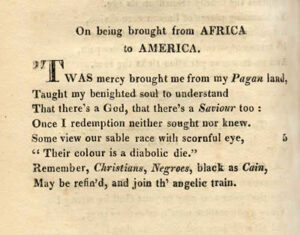

Phillis Wheatley was a prolific writer and poet who rose to international recognition during the time of the American Revolution. Born in 1753 in Africa, she was kidnapped and enslaved to a Bostonian family, where she learned to read and write. Her magnum opus, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), demonstrates the extent of her poetic genius as well as her subtle jabs at the ideological hypocrisy running rampant on the issues of slavery and the limits of Christian love. One such poem from this collection, On Being Brought From Africa To America, perfectly demonstrates Wheatley’s precision and intellect. Virtually every line of this poem possesses somewhat of a double entendre, dual interpretations of the same text. That literary cleverness allowed her to compose a work that retains interpretations of genuine gratitude and bitter resentment within the same text.

Like many of the enslaved people of the time, Wheatley was converted to Christianity when she was first subjugated at the age of seven. According to Christian doctrine, her conversion guaranteed her salvation. This idea is reflected in her poetry. Wheatley writes, “Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land…That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: once I redemption neither sought nor knew.” Here she expresses her gratitude and acknowledges that without her forced relocation from Africa, she would not be able to relish in the joys of her salvation. Contrarily, this same text can be read as condescending and somewhat scornful. The use of the italics with Pagan and Saviour allows Wheatley to show her dissatisfaction with that idea. That ideology paints the fictitious depiction of savages that, for their own good, were forcibly assimilated and stripped of their freedoms. She is expressing bitter resentment at this false narrative of white saviors. It reverses an acclaim-full tone into one full of disdain. Wheatley, like many of her compatriots, did not ask to be saved by white slave traders. She did not actively seek out christendom, nor even knew of its existence. What appears to be Wheatley expressing a minor detail of her religious journey quickly turns into a crucial detail of her reality.

Later in the poem, Wheatley writes “Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join the’ angelic train.” She is reminding all Christians that regardless of race, those who found solace and redemption within Christianity are all promised the same rewards. Within that syncopal phrase, she reminds the audience that all are equal within the eyes of the Lord. Although some view her race as the equivalent of the mark of Cain, a somewhat demonic sign of her malevolence, Wheatley believes that God judges everyone identically and holds them to the same standards. This idea of divine love beyond physical appearance is a central theme of Wheatley’s poem, and leads many to credit her work as a representation of her appreciation and fortunate demeanor towards her enslavement and subsequent redemption. Reversley, this same line of text can be explained as the allusion to the mark of Cain supporting the idea that her race alone is a sign of inferiority under the Lord. Many within the church endorsed the institution, actively encouraging the hypocrisy of their own dogma.

Courtesy of UK National Archives

The entire premise of Christian love is supposed to promote equality and camaraderie between humankind. This idea of racial subjugation directly goes against that. Wheatley’s display of this blatant dismissal of critical teachings within the church demonstrates the extent of her begrudgement. Her resentment stemmed from the fact that even within her own religion, where she was supposed to find acceptance and toleration, she instead was met with racism. These concepts ultimately led to, however subtly, her integrating a tone of irritation and displeasure in what would appear as a poem of great praise.