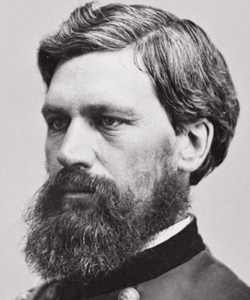

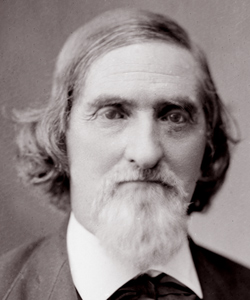

In 1873, a decade after his heroic defense of Little Round Top, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain faced another rebellion. Upon taking office as president of Bowdoin College in 1871, Chamberlain had instituted mandatory military drill for all Bowdoin students. Students complained about the military discipline and the expense of a military uniform (six dollars added to the cost of attending Bowdoin), and soon President Chamberlain had a full-scale rebellion on his hands.

In 1873, a decade after his heroic defense of Little Round Top, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain faced another rebellion. Upon taking office as president of Bowdoin College in 1871, Chamberlain had instituted mandatory military drill for all Bowdoin students. Students complained about the military discipline and the expense of a military uniform (six dollars added to the cost of attending Bowdoin), and soon President Chamberlain had a full-scale rebellion on his hands.

Eventually, after he lost the support of the college trustees, Chamberlain was forced to back down.

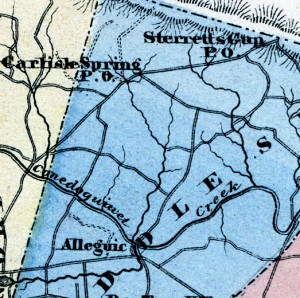

Chamberlain was himself an 1856 graduate of Bowdoin. He had prepared for his entrance examination by working with a private tutor and spending as many as seventeen hours a day teaching himself ancient Greek. He also spent a year, when he was fourteen, attending the Military and Classical Academy in Ellsworth, Maine, where he was drilled by headmaster Charles Jarvis Whiting. From the former Army engineer, Chamberlain received his first taste of military discipline.

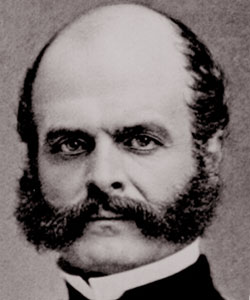

As President of Bowdoin after the war, Chamberlain not only instituted military drill, he also turned his attention to improving the college’s offerings in the practical disciplines of science and engineering. He began to urge Maine’s wealthy former governor, Abner Coburn, to endow a new “scientific department” at Bowdoin. He told Coburn: “I took this place [as college president] simply because I thought I could here soonest and best try the experiment of a liberal course of study which should tend to the widest practical use in life. The great demand of the times is that knowledge, instead of being turned inward, and shut up in the cloister, should face outward towards the real work of life” (The Grand Old Man of Maine, pp. 53-4)

Chamberlain admired the accomplishments of educators like Ezra Cornell and Harvard president Charles William Eliot, who were leading the effort to modernize higher education in America. Ezra Cornell had founded the university that bears his name in 1865, under the provisions of the Morrill Act, the Civil War era legislation which provided federal land grants for colleges. The act required land-grant colleges, “without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactic, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.”

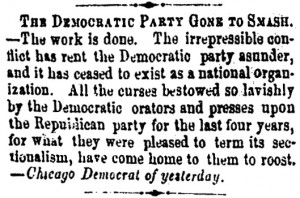

The period from 1840 to 1880 brought to prominence practical-minded men like Eliot (a chemist and businessman), Cornell (the founder of Western Union), and Chamberlain, who realized that the traditional classical curriculum, with its focus on Latin and Greek, was insufficient for a practical, democratic society like the United States. Ironically, the period ended with the election of James A. Garfield—the first and only professor of classical languages to serve as President of the United States.

Bowdoin College maintains an informative digital archive of resources related to the life and career of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, including documents, photographs, and a “biographical map” using Google Maps or Google Earth. The most recent biography of Chamberlain is Edward G. Longacre’s Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man (Da Capo Press 2003).