Standing on the ground at the battlefields of Gettysburg is both a breathtaking, yet unsatisfying experience. Realizing that your feet are touching the same ground as men who died for a heroic cause brings humility, perspective, and a strong connection with history that cannot be experienced in an ordinary classroom. However, there remains a sense of disconnect from the souls of people, which site-seeing itself cannot satisfy. This missing connection, perhaps, is one that can only be attained through the careful teaching of stories that invoke that which will unite humanity for all time: emotion. When placed in its proper context, emotional stories not only bridge the gap between past and present, but also provide a better understanding for the events themselves. With the powerful combination of primary sources and modern technology, teachers are able to use these types of stories today more effectively than ever before from their own classrooms.

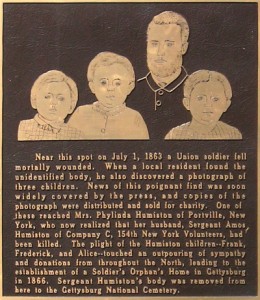

As a summer intern for Professor Pinsker at Dickinson College, I had the privilege to travel with him to Gettysburg as he led a group of high school teachers from Oklahoma on a tour of the battlegrounds. Before the trip, he asked me to be thinking about a story that I believe is especially impactful, and how I would use it to teach high school students about history and the Civil War. After some of the more well-known sites, we eventually stopped at a fire station on Stratton Street. It was here that I first heard the story of Amos Humiston, a soldier who died on that very ground almost 150 years ago, with a photo of his three children clutched in his hand. Humiston’s emotional story immediately interested me, and after talking with several of the high school teachers there about the needs and struggles of their students to understand history, I realized that Amos Humiston could potentially fill the gap. A little known story from the Battle of Gettysburg, his is one that nonetheless can be used to capture both the context of the times and heart of a soldier, while also providing opportunites for students to take a historians approach to the past.

Providing Context

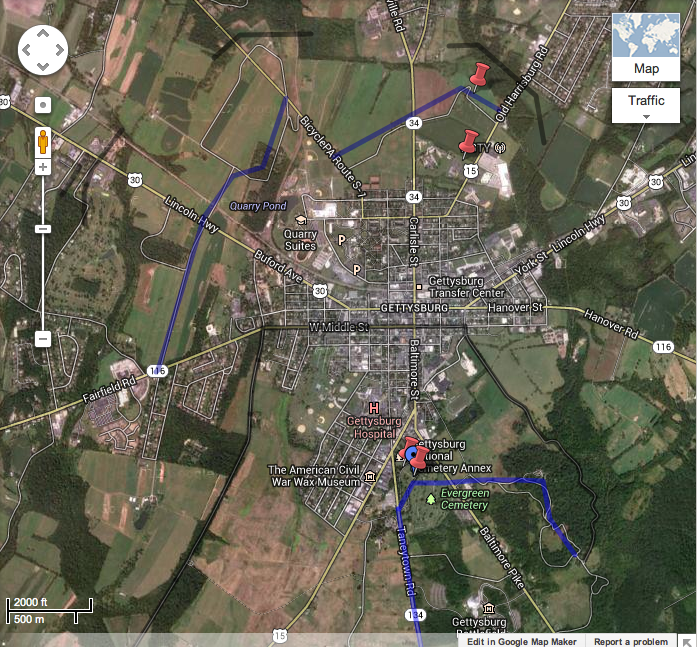

To gain initial background and perspective, students should become familiar with a textbook explanation of the Battle of Gettysburg. To add interest and depth, media sites such as Google Earth show fantastic views of the landscape, and maps or pictures from sites like House Divided show the military strategy and devastation of the battle.

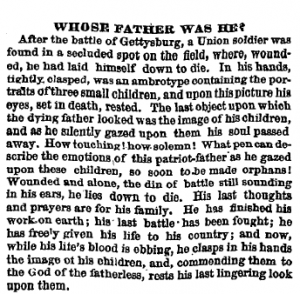

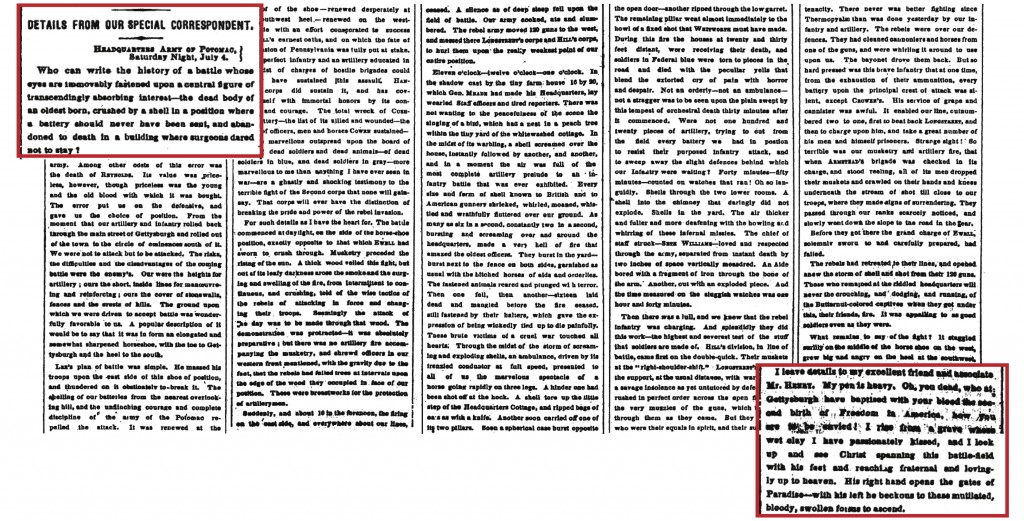

Once students have grasped an overall understanding of the Gettysburg Campaign, provide the students with a copy of an article from the October 19, 1863 Philadelphia Inquirer titled “Whose Father Was He?” Have the students analyze the document, and write down what they think it tells them about the war, family, and religion at the time.

An article printed in the Philadelphia Inquirer on October 19,

For more background and better analysis, the students could also read several paragraphs on pages 6 & 7 from Drew Gilpin Faust’s book titled The Republic of Suffering. In it, she explains the meaning and importance of “The Good Death” during the Civil War, describing how soldiers sought to be at peace with God and die honorably.

Relating to the Past

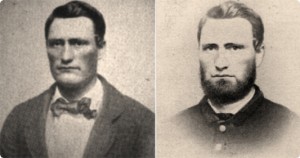

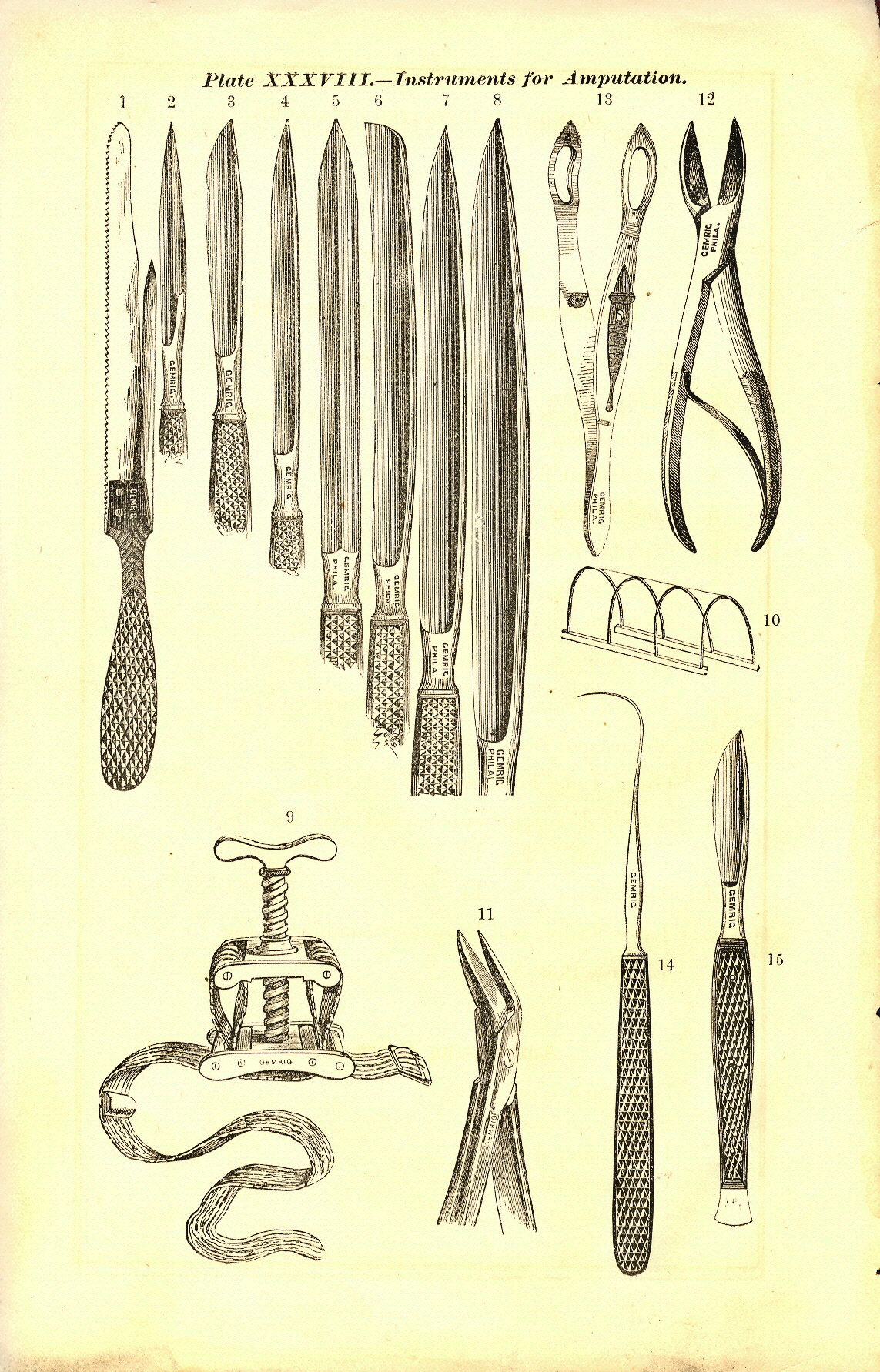

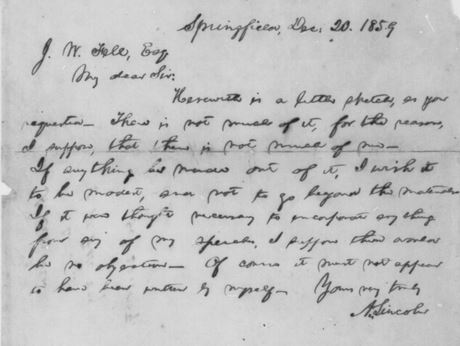

Once the students complete this task, go on to identify the unknown soldier from the Philadelphia Inquirer as Amos Humiston, and explain his story. A detailed version of the story can by found in a five-part blog post by Errol Morris for the New York Times titled “Whose Father Was He.” In addition, a shortened handout version along with a brief video can be found on the Day 1 Gettysburg Virtual Tour for the House Divided website. Use photos of he and his children as visual aids, and provide the students with examples of his letters and poems. In addition, students could even write thier own poem or letter to thier family as if they were a soldier at the time. These devices and techniques are very helpful in getting students to empathize with people from the past, and provide a strong connection to their emotions.

Writing Like Historians

After the students have gained an understanding of the context in which Amos Humiston lived and have identified with him emotionally, they must then begin to write as historians. Have them use everything they have learned thus far about Humiston from primary and secondary sources, and instruct them to write a brief memorial about him for the Gettysburg Battlefield. While brief, it will allow them to think critically about how to approach the past, and provide them with writing techniques that will be beneficial in future research papers. To conclude, a picture of the actual Gettysburg monument to Amos Humiston can be shown and read in class.

While there is no real substitute for a field trip to Gettysburg, modern technology has provided an opportunity for individuals to engage the past in significant ways. The high availability of primary and secondary sources over the internet allow teachers to present history to their students both accurately and creatively. Captivating stories such as Amos Humiston allow for the perfect combination of these sources and show students (if only a glimpse) of how real historians operate.

For even further reading on Amos Humiston, see:

Mark H. Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier: The Life, Death and Celebrity of Amos Humiston (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1999)

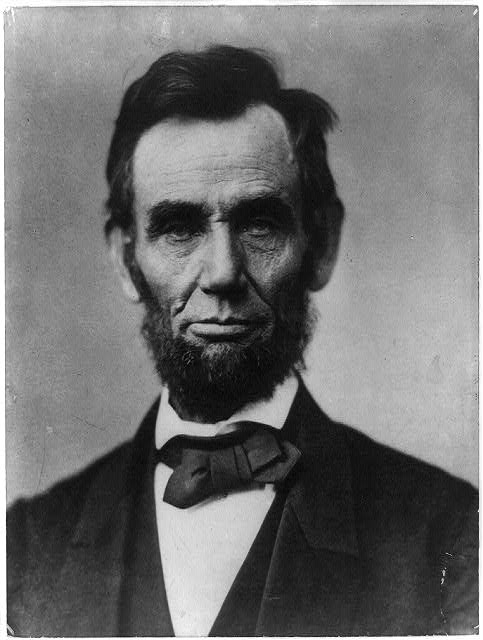

One of the several critical strands in the “Lincoln” movie concerns the controversy surrounding the Hampton Roads peace talks (February 3, 1865), where President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward met with Confederate envoys Alexander Stephens, John Campbell and Robert M.T. Hunter for secret discussions about how to end the war on board the River Queen in Union-controlled Hampton Roads, Virginia (near Fortress Monroe). No transcript exists for their conversations that day. Lincoln and Seward died before leaving any recollection of the affair. So historians have mostly relied upon on the dubious

One of the several critical strands in the “Lincoln” movie concerns the controversy surrounding the Hampton Roads peace talks (February 3, 1865), where President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward met with Confederate envoys Alexander Stephens, John Campbell and Robert M.T. Hunter for secret discussions about how to end the war on board the River Queen in Union-controlled Hampton Roads, Virginia (near Fortress Monroe). No transcript exists for their conversations that day. Lincoln and Seward died before leaving any recollection of the affair. So historians have mostly relied upon on the dubious  According to the “Lincoln” movie script, Friday, January 27, 1865 was an action-packed and pivotal day. It was the day of Thaddeus Stevens’s controlled performance in the House, declaring himself strictly for “equality before the law.” It was also the day marked by Abraham Lincoln’s bitter argument with his oldest son Robert and then his subsequent clash with his wife Mary after he finally decided to concede to Robert’s desire to join the Union army. And it was in the evening of the 27th that both Mary Lincoln and later dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley urged the president to abandon his hidden-hand approach and provide more decisive leadership in the fight for the antislavery amendment. All of those “events” are fictional, but they are essential for understanding the film’s point-of-view –namely, that Lincoln interjected himself at the end of the battle for the constitutional amendment in a way that proved decisive.

According to the “Lincoln” movie script, Friday, January 27, 1865 was an action-packed and pivotal day. It was the day of Thaddeus Stevens’s controlled performance in the House, declaring himself strictly for “equality before the law.” It was also the day marked by Abraham Lincoln’s bitter argument with his oldest son Robert and then his subsequent clash with his wife Mary after he finally decided to concede to Robert’s desire to join the Union army. And it was in the evening of the 27th that both Mary Lincoln and later dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley urged the president to abandon his hidden-hand approach and provide more decisive leadership in the fight for the antislavery amendment. All of those “events” are fictional, but they are essential for understanding the film’s point-of-view –namely, that Lincoln interjected himself at the end of the battle for the constitutional amendment in a way that proved decisive. The filmmakers present this exchange in the most dramatic fashion possible, having Democratic leader Fernando Wood (D, NY) first disrupt the proceedings, allegedly waving “affidavits from loyal citizens” confirming the existence of secret peace talks. This creates chaos on the floor of the House that leads a fictional “conservative” Republican named Aaron Haddam to indicate (after receiving a critical nod from Preston Blair, perched in the gallery) that the “conservative faction of border and western Republicans” could not support an amendment “if a peace offer is being held hostage to its success.” Then there is a mad footrace from the Capitol to the White House, involving Lincoln’s aides and the Seward lobbyists. John Hay, the president’s young assistant private secretary, heatedly warns him against “making false representation” but Lincoln crafts his reply (technically true but obviously deceptive –since the commissioners were on their way to Hampton Roads, VA) and hands the note to seasoned lobbyist William N. Bilbo (James Spader). Bilbo then delivers it to Rep. Ashley who reads it with a flourish to the entire House. There is no record of any of this in the official proceedings. Nor does Ashley claim in his recollection that he read the note from the president on the House floor. Instead, it seems he may have simply showed it to some key figures. Bilbo was not even in Washington at the time (see previous post

The filmmakers present this exchange in the most dramatic fashion possible, having Democratic leader Fernando Wood (D, NY) first disrupt the proceedings, allegedly waving “affidavits from loyal citizens” confirming the existence of secret peace talks. This creates chaos on the floor of the House that leads a fictional “conservative” Republican named Aaron Haddam to indicate (after receiving a critical nod from Preston Blair, perched in the gallery) that the “conservative faction of border and western Republicans” could not support an amendment “if a peace offer is being held hostage to its success.” Then there is a mad footrace from the Capitol to the White House, involving Lincoln’s aides and the Seward lobbyists. John Hay, the president’s young assistant private secretary, heatedly warns him against “making false representation” but Lincoln crafts his reply (technically true but obviously deceptive –since the commissioners were on their way to Hampton Roads, VA) and hands the note to seasoned lobbyist William N. Bilbo (James Spader). Bilbo then delivers it to Rep. Ashley who reads it with a flourish to the entire House. There is no record of any of this in the official proceedings. Nor does Ashley claim in his recollection that he read the note from the president on the House floor. Instead, it seems he may have simply showed it to some key figures. Bilbo was not even in Washington at the time (see previous post  No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war.

No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war. Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in

Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in  In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.

In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.  Smith

Smith Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities.

Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities.  The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that

The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that  Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.

Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.