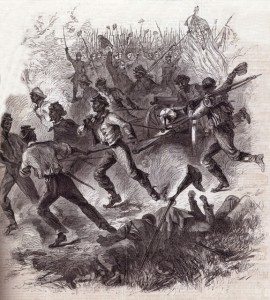

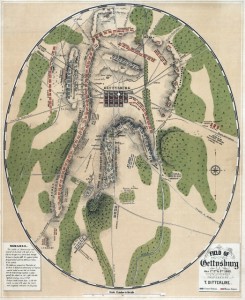

The Battle of the Crater (also known as The Mine) took place on July 30, 1864 in Petersburg, Virginia. Union forces under the command of Major General Ambrose E. Burnside exploded a mine and created a large gap in the Confederate protection of Petersburg. However, the Confederate Major General William Mahone and his forces responded with various counterattacks that resulted in high casualties for the Union forces, especially the United States Colored Troop Regiments present. The National Parks Service website provides a detailed summary of the Battle of the Crater that includes several sketches of the battlefield. The Civil War Preservation Trust’s website offers several resources on the battle such as an article on the Petersburg Campaign and short biographies of Union General Burnside and Confederate General Robert E. Lee. John F. Schmutz recounted the battle in his book, The Battle of the Crater: A Complete History:

“Whenever the first division attempted to advance out of the Crater, they were soon met by intense fire from the Confederate infantry, which had by then recovered its composure after the explosion and bombardment, as well as the Rebel artillery, which had found the range on the Federals in the Crater. Many were hit not only from the exposed flanks, but also from the rear, as the Confederates reoccupied the transverses and entrenchments to the right and left of the Crater. These men had recovered their equanimity and when the Union attempted to re-form on the Confederate side of the Crater, the Rebels faced about and delivered a fire into the backs of the Federals. Coming so unexpectedly, this caused the forming line to fall back into the Crater.”

Another resource which may be interesting to browse is Edward Alexander Porter’s Fighting for the Confederacy: the Personal Recollections of General Edward Alexander Porter which provides a firsthand account of the battle from the Confederate perspective. Also available on Google Books as a preview is Earl Hess’s In the Trenches at Petersburg which gives a summary of the action at the Crater as well as a map of the battlefield. The Battle of the Crater could be connected to a lesson on United States Colored Troops in the Civil War as a previous post on Blog Divided gives details on the participation of the 43rd USCT Regiment during the battle. For further reading, Gregory J.W. Urwin’s Black Flag over Dixie and John David Smith’s Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era both provide an account of the experiences of black soldiers during the Battle of the Crater.