Contributing Editors for this page include Marsha Greco, Kory Loyola, Greg O’Reilly and Cynthia Smith

Ranking

#75 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“And, as this subject is no other, than part and parcel of the larger general question of domestic-slavery, I wish to MAKE and to KEEP the distinction between the EXISTING institution, and the EXTENSION of it, so broad, and so clear, that no honest man can misunderstand me, and no dishonest one, successfully misrepresent me….”

On This Date

HD Daily Report, October 16, 1854

The Lincoln Log, October 16, 1854

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” course participant Greg O’Reilly, August 2014. You can read a transcript of this video here.

Marsha Greco, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), October 1, 2013

Kory Loyola, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), September 29, 2013

Cynthia Smith, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), September 4, 2013

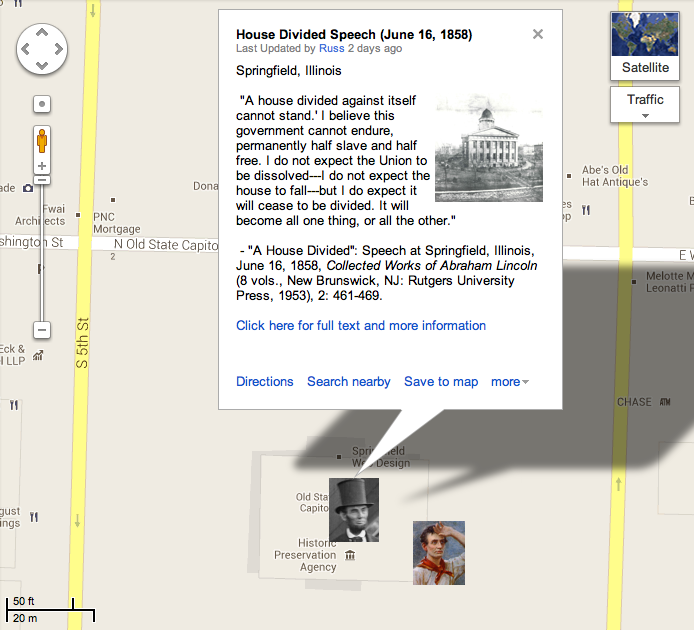

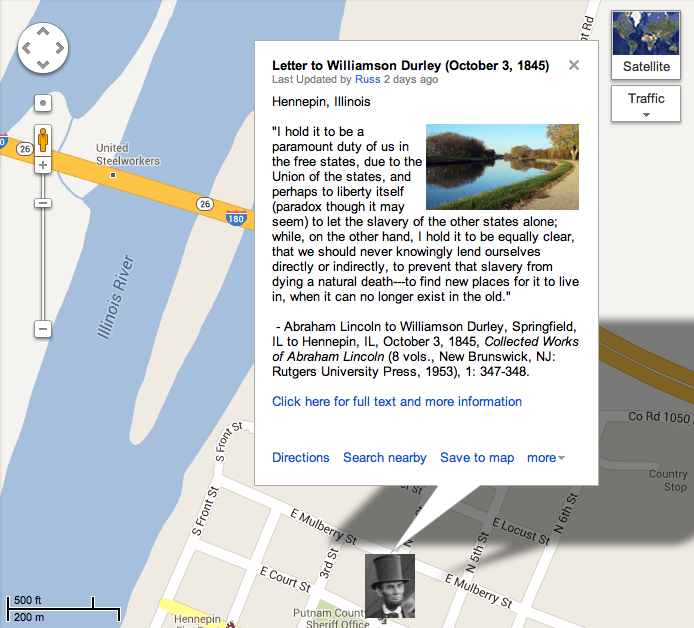

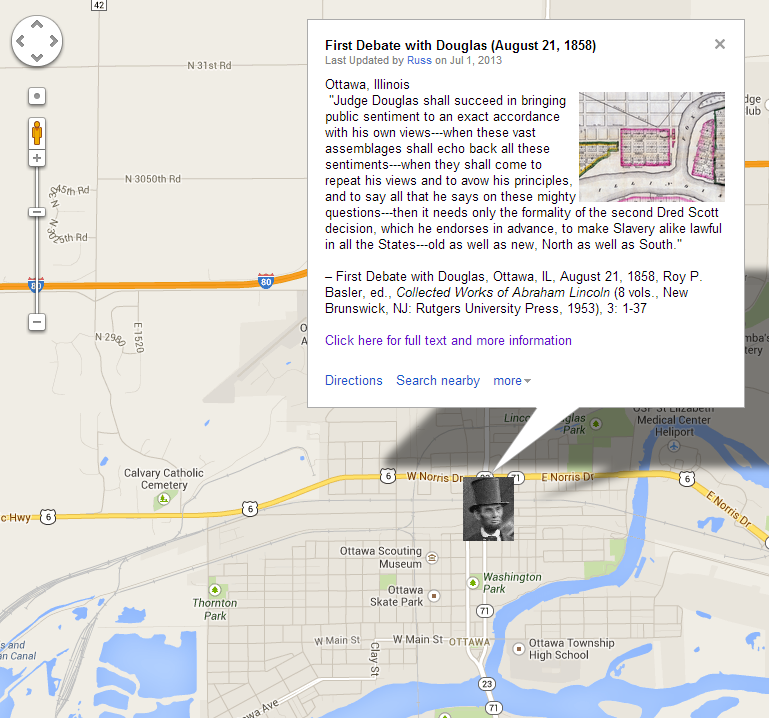

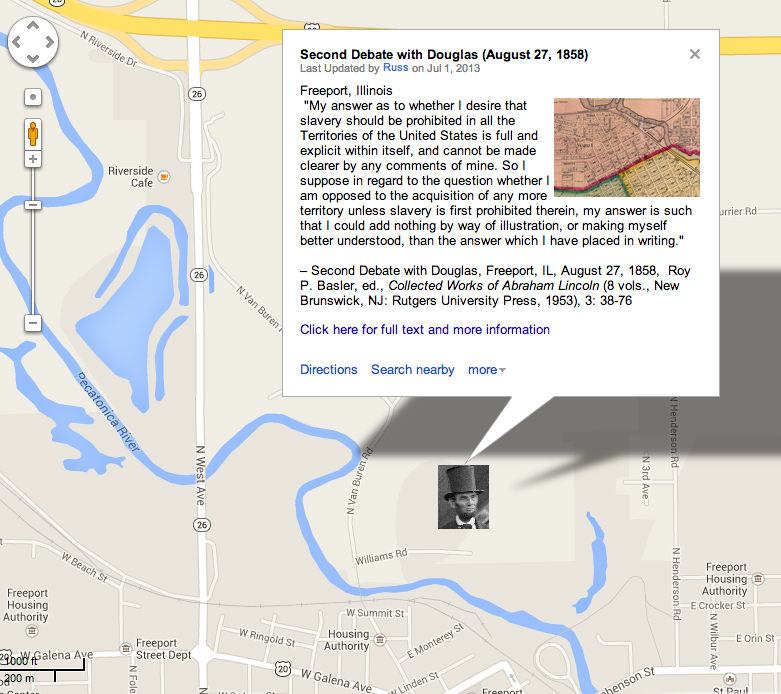

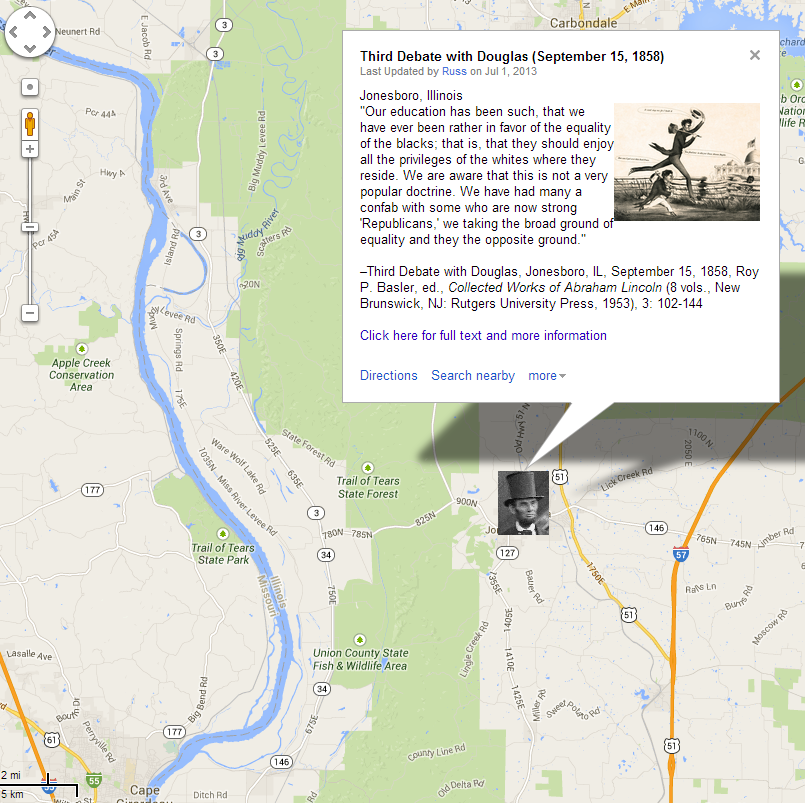

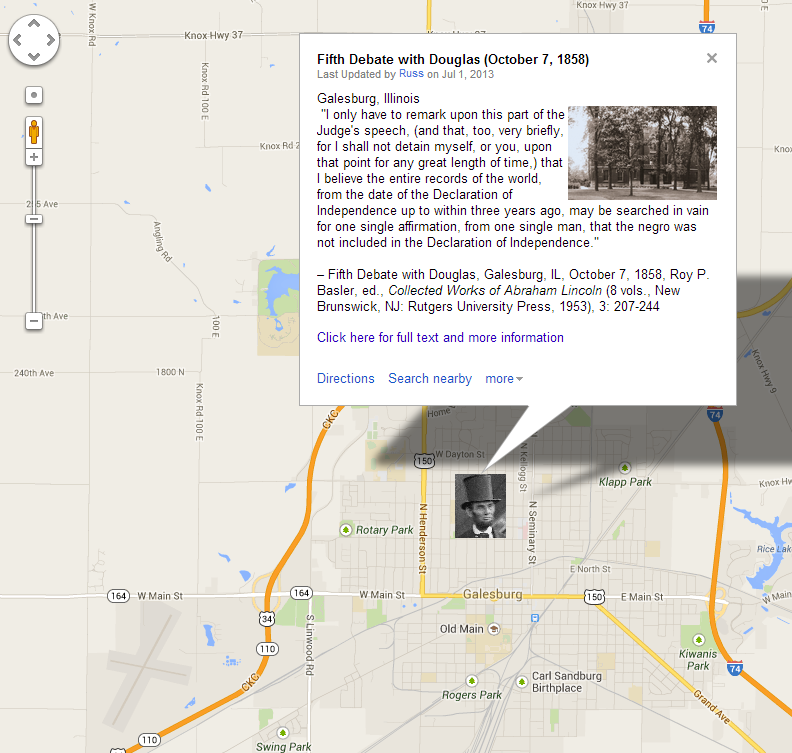

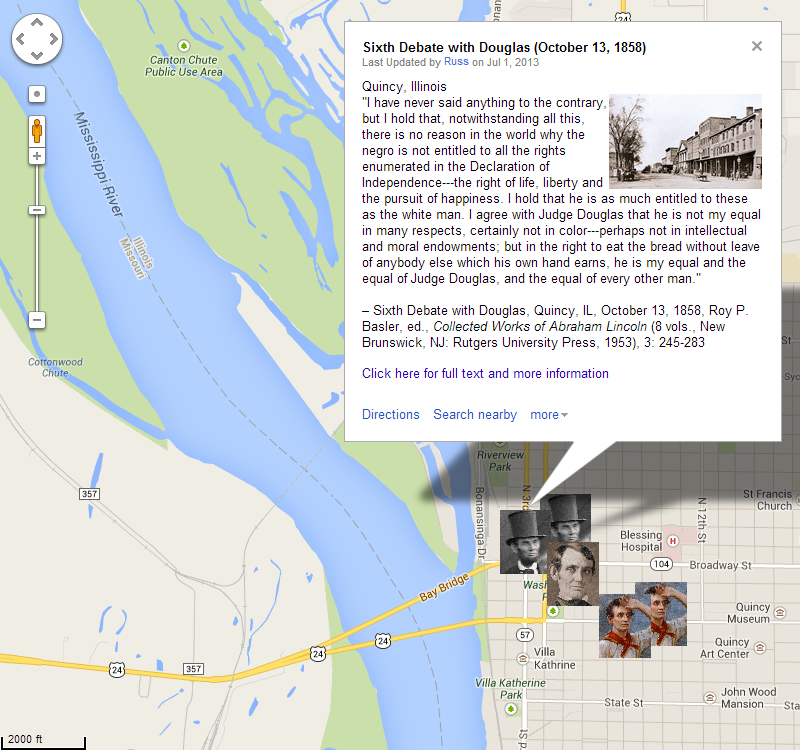

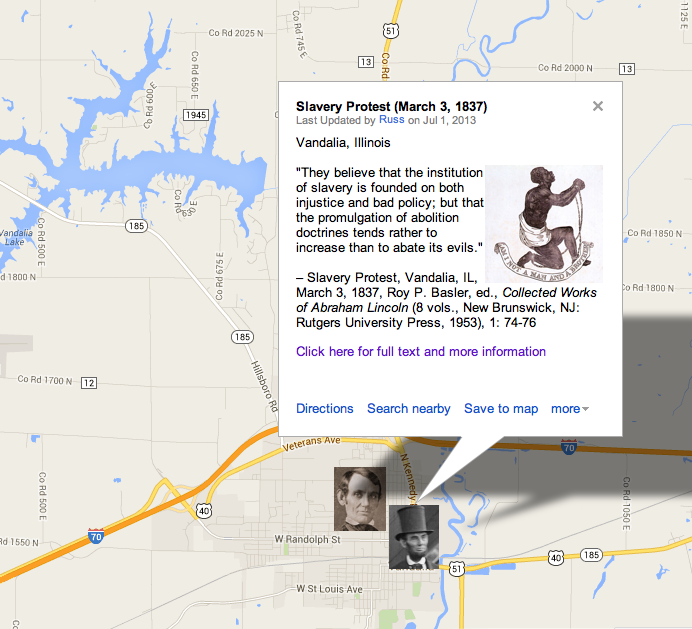

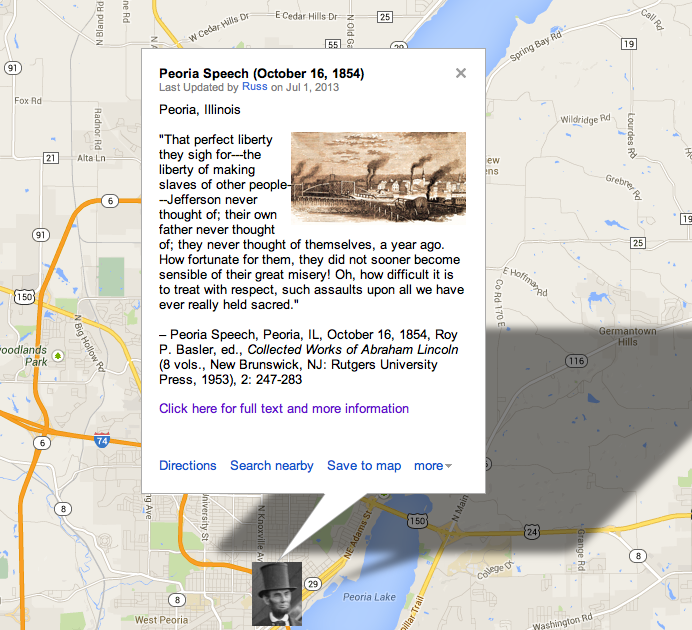

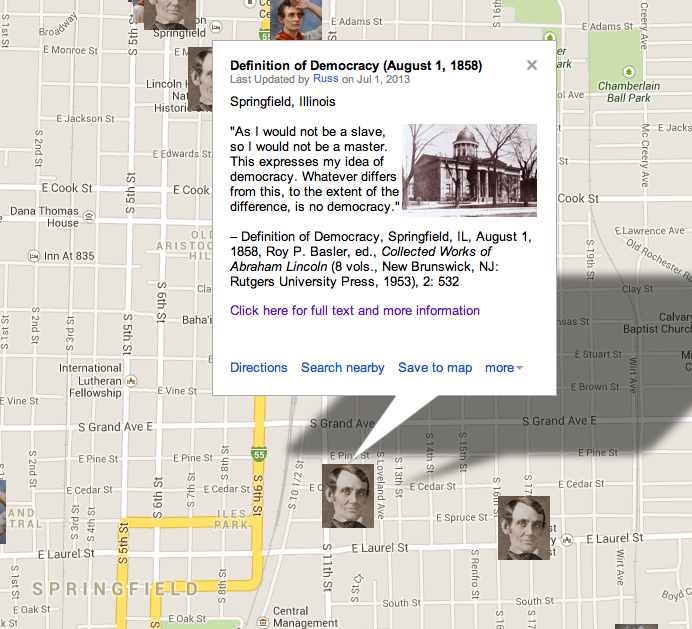

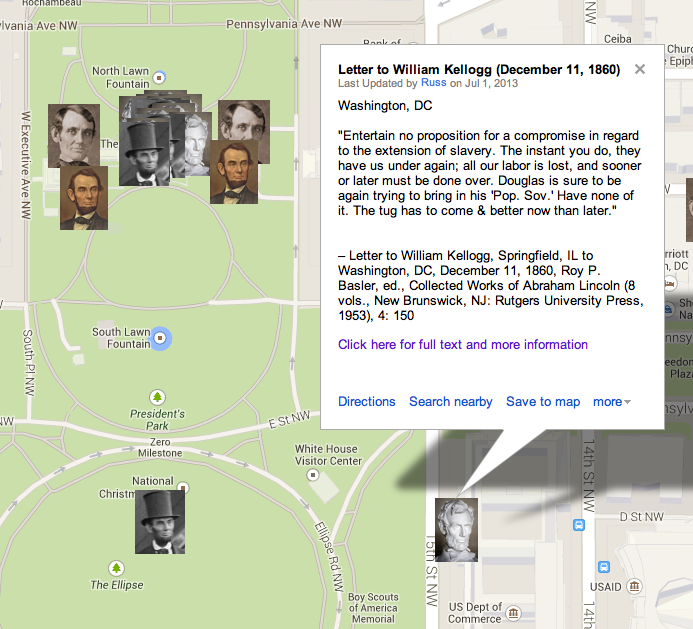

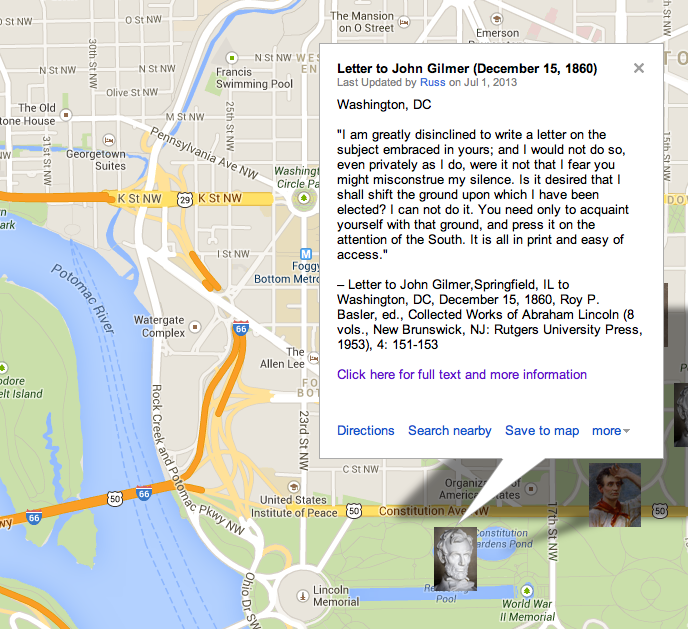

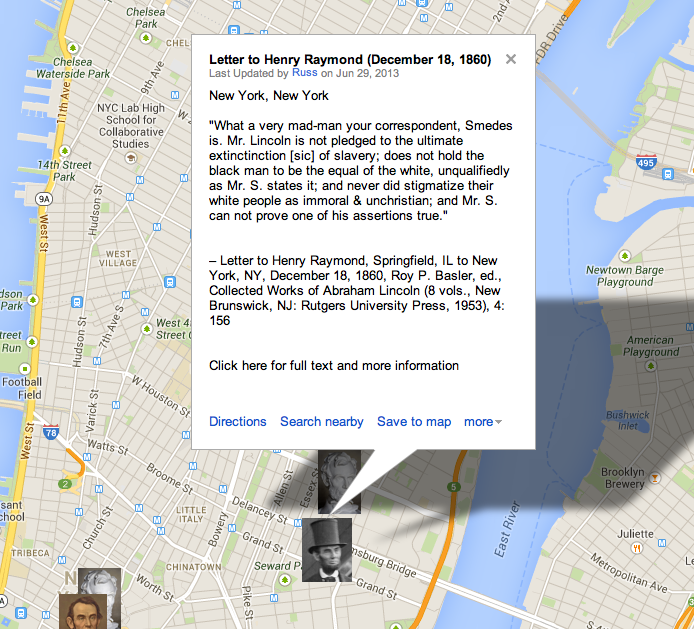

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

How Historians Interpret

“Lincoln’s October 1854 speech at Peoria would be, perhaps, his most ringing condemnation of popular sovereignty. Carwardine says that the speech ‘contained most of the essential elements of his public addresses over the next six years.’ At Peoria, Lincoln deplored the Kansas-Nebraska Act for resuscitating, not calming, slavery agitation. He avowed suspicions that popular sovereignty really intended to spread slavery. He condemned slavery as both a “monstrous injustice” and a betrayal of ‘our republican example.’ He asserted that if blacks are men, which he considered self-evident, they were entitled to equality under the Declaration of Independence. He denied that ‘there can be MORAL RIGHT in the enslaving of one man by another.’ Douglas drew legitimacy for popular sovereignty from the supremacy of self-government in the ideology of nineteenth-century Americans. Lincoln, seeking to deny that self-government applied in this case, turned to the prestige of the Revolutionary generation. ‘The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms, and the former is being rapidly displaced by the latter.'”

—Nicole Etcheson, “‘A living, creeping lie’: Abraham Lincoln on Popular Sovereignty”, Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 29, 2008.

“A Democratic newspaper in Peoria attacked Lincoln for virtually sanctioning miscegenation. In arguing ‘that no people were good enough to legislate for another people without that other’s consent; or in other words:—the people of Nebraska are not competent to legislate for the negro without the negro’s consent,’ Lincoln had denied the legitimacy of Illinois’ constitutional provision forbidding whites and blacks to marry. After all, the paper asserted, that prohibition was made ‘without consulting the feelings of the negroes.’ So if Lincoln is correct, ‘our laws ‘with adequate penalties, preventing the intermarriage of whites with blacks’ and that ‘no colored person shall ever under any pretext, be allowed to hold any office of honor or profit in tis state,’ ARE ALL WRONG, because each of these provisions have been adopted without the consent of the negro.’ The Peoria Republican took a more favorable view of ‘Lincoln’s truly able and masterly speech.’ The editors said that had ‘never heard the subjects treated so eloquently handled, nor have we often seen a speaker acquit himself with greater apparent ease and self-possession.’”

—Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Live, Volume 1, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

… The repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and the propriety of its restoration, constitute the subject of what I am about to say.

As I desire to present my own connected view of this subject, my remarks will not be, specifically, an answer to Judge Douglas; yet, as I proceed, the main points he has presented will arise, and will receive such respectful attention as I may be able to give them.

I wish further to say, that I do not propose to question the patriotism, or to assail the motives of any man, or class of men; but rather to strictly confine myself to the naked merits of the question.

I also wish to be no less than National in all the positions I may take; and whenever I take ground which others have thought, or may think, narrow, sectional and dangerous to the Union, I hope to give a reason, which will appear sufficient, at least to some, why I think differently.

And, as this subject is no other, than part and parcel of the larger general question of domestic-slavery, I wish to MAKE and to KEEP the distinction between the EXISTING institution, and the EXTENSION of it, so broad, and so clear, that no honest man can misunderstand me, and no dishonest one, successfully misrepresent me….

… In 1853, a bill to give it a territorial government passed the House of Representatives, and, in the hands of Judge Douglas, failed of passing the Senate only for want of time. This bill contained no repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Indeed, when it was assailed because it did not contain such repeal, Judge Douglas defended it in its existing form. On January 4th, 1854, Judge Douglas introduces a new bill to give Nebraska territorial government. He accompanies this bill with a report, in which last, he expressly recommends that the Missouri Compromise shall neither be affirmed nor repealed.

Before long the bill is so modified as to make two territories instead of one; calling the Southern one Kansas.

Also, about a month after the introduction of the bill, on the judge’s own motion, it is so amended as to declare the Missouri Compromise inoperative and void; and, substantially, that the People who go and settle there may establish slavery, or exclude it, as they may see fit. In this shape the bill passed both branches of congress, and became a law.

This is the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. The foregoing history may not be precisely accurate in every particular; but I am sure it is sufficiently so, for all the uses I shall attempt to make of it, and in it, we have before us, the chief material enabling us to correctly judge whether the repeal of the Missouri Compromise is right or wrong.

I think, and shall try to show, that it is wrong; wrong in its direct effect, letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska—and wrong in its prospective principle, allowing it to spread to every other part of the wide world, where men can be found inclined to take it.

This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticising the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

Before proceeding, let me say I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist amongst them, they would not introduce it. If it did now exist amongst us, we should not instantly give it up. This I believe of the masses north and south. Doubtless there are individuals, on both sides, who would not hold slaves under any circumstances; and others who would gladly introduce slavery anew, if it were out of existence. We know that some southern men do free their slaves, go north, and become tip-top abolitionists; while some northern ones go south, and become most cruel slave-masters.

When southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery, than we; I acknowledge the fact. When it is said that the institution exists; and that it is very difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying. I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself. If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia,—to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world to carry them there in many times ten days. What then? Free them all, and keep them among us as underlings? Is it quite certain that this betters their condition? I think I would not hold one in slavery, at any rate; yet the point is not clear enough for me to denounce people upon. What next? Free them, and make them politically and socially, our equals? My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not. Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment, is not the sole question, if indeed, it is any part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, can not be safely disregarded. We can not, then, make them equals. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted; but for their tardiness in this, I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the south.

When they remind us of their constitutional rights, I acknowledge them, not grudgingly, but fully, and fairly; and I would give them any legislation for the reclaiming of their fugitives, which should not, in its stringency, be more likely to carry a free man into slavery, than our ordinary criminal laws are to hang an innocent one.

But all this; to my judgment, furnishes no more excuse for permitting slavery to go into our own free territory, than it would for reviving the African slave trade by law. The law which forbids the bringing of slaves from Africa; and that which has so long forbid the taking them to Nebraska, can hardly be distinguished on any moral principle; and the repeal of the former could find quite as plausible excuses as that of the latter….

…But Nebraska is urged as a great Union-saving measure. Well I too, go for saving the Union. Much as I hate slavery, I would consent to the extension of it rather than see the Union dissolved, just as I would consent to any GREAT evil, to avoid a GREATER one. But when I go to Union saving, I must believe, at least, that the means I employ has some adaptation to the end. To my mind, Nebraska has no such adaptation.

“It hath no relish of salvation in it.”

It is an aggravation, rather, of the only one thing which ever endangers the Union. When it came upon us, all was peace and quiet. The nation was looking to the forming of new bonds of Union; and a long course of peace and prosperity seemed to lie before us. In the whole range of possibility, there scarcely appears to me to have been any thing, out of which the slavery agitation could have been revived, except the very project of repealing the Missouri compromise. Every inch of territory we owned, already had a definite settlement of the slavery question, and by which, all parties were pledged to abide. Indeed, there was no uninhabited country on the continent, which we could acquire; if we except some extreme northern regions, which are wholly out of the question. In this state of case, the genius of Discord himself, could scarcely have invented a way of again getting [setting?] us by the ears, but by turning back and destroying the peace measures of the past. The councils of that genius seem to have prevailed, the Missouri compromise was repealed; and here we are, in the midst of a new slavery agitation, such, I think, as we have never seen before.

Who is responsible for this? Is it those who resist the measure; or those who, causelessly, brought it forward, and pressed it through, having reason to know, and, in fact, knowing it must and would be so resisted? It could not but be expected by its author, that it would be looked upon as a measure for the extension of slavery, aggravated by a gross breach of faith. Argue as you will, and long as you will, this is the naked FRONT and ASPECT, of the measure. And in this aspect, it could not but produce agitation. Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man’s nature—opposition to it, is [in?] his love of justice. These principles are an eternal antagonism; and when brought into collision so fiercely, as slavery extension brings them, shocks, and throes, and convulsions must ceaselessly follow. Repeal the Missouri compromise—repeal all compromises—repeal the declaration of independence—repeal all past history, you still can not repeal human nature. It still will be the abundance of man’s heart, that slavery extension is wrong; and out of the abundance of his heart, his mouth will continue to speak….”