“I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

INTRODUCTION

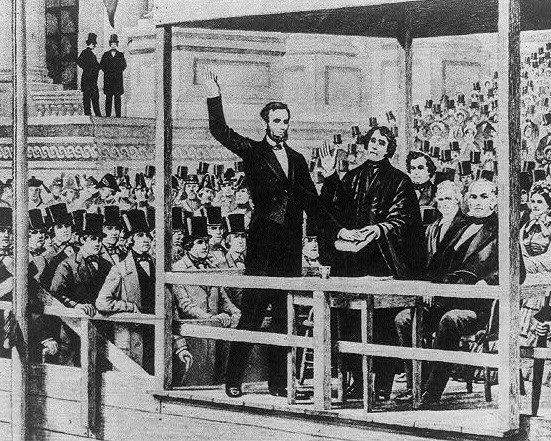

Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) won election as the nation’s sixteenth president in November 1860 after a complicated four-way contest that took place during a period of bitter sectional polarization. Following his victory, seven out of fifteen slave states claimed that they were leaving the union or seceding to form a new government, which they called the Confederate States of America. Most white southerners seemed terrified that once antislavery Republicans held control of the federal government, they would abolish slavery

. Lincoln tried to use his Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861, to calm their nerves. In particular, Lincoln appeared to employ this ceremonial speech to try to dissuade Upper South states from joining a rebellion against the nation. Although the new president acknowledged in this excerpt that there was a “substantial dispute” over slavery’s morality, he denied that Republicans were planning to attack the institution in states where it had long existed. Instead, he claimed his party would honor longstanding constitutional compromises over slavery, though without allowing any further extension into the western territories. Lincoln also blasted secession, calling it “the essence of anarchy,” because he believed it would forever undermine the principles of representative self-government. Lincoln ended by appealing to patriotism and shared national heritage. Nevertheless, just a short six weeks after this powerful speech, Confederate troops fired on US military forces at Fort Sumter in South Carolina and the Civil War began.

SOURCE FORMAT: Public speech (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 700 words

Excerpt from Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, read and produced by Ariana Suggs, Summer 2022

Abraham Lincoln, Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861

…Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that:

“I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

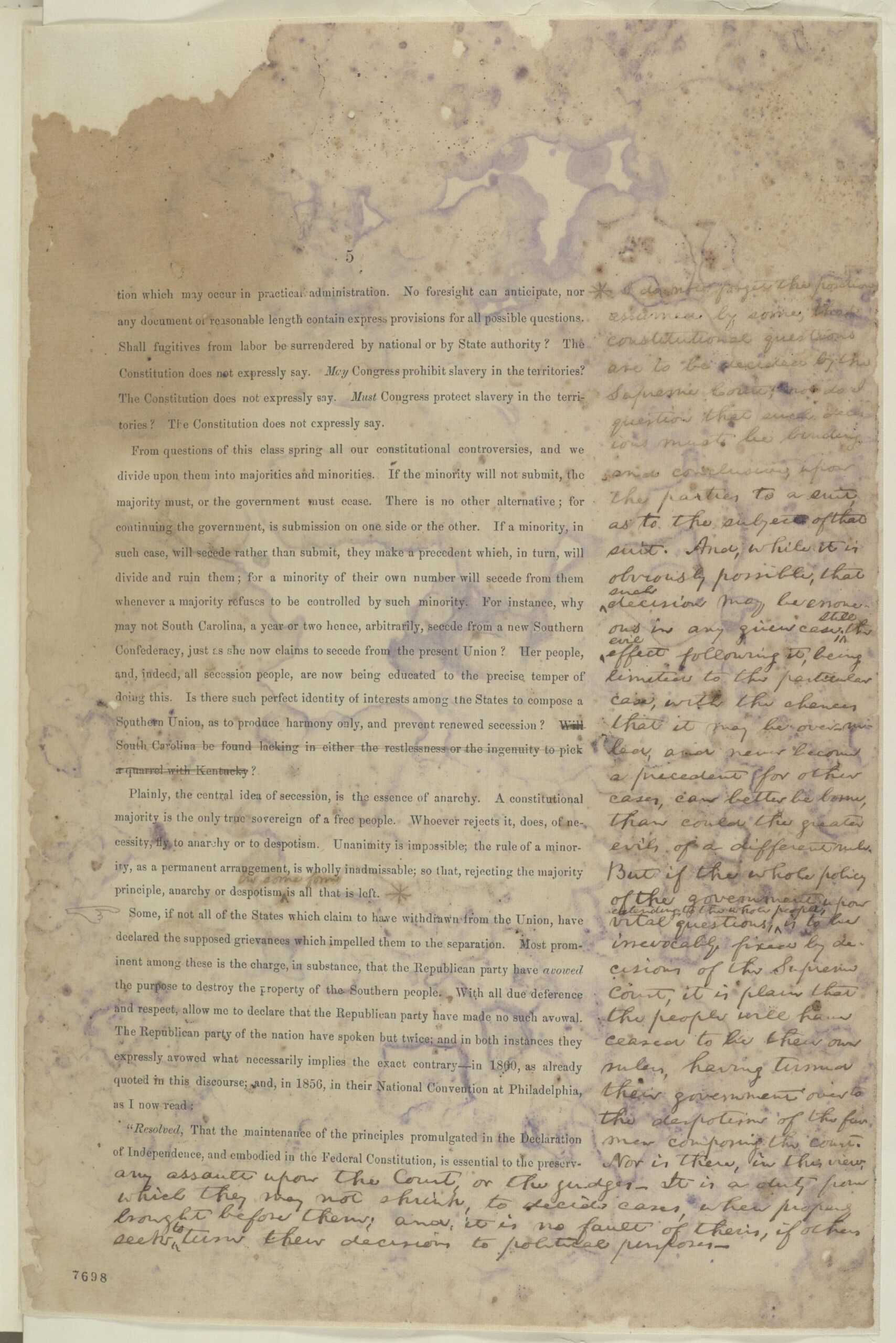

Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations and had never recanted them; and more than this, they placed in the platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read:

“Resolved, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.”

… Plainly, the central idea of secession, is the essence of anarchy. A majority, held in restraint by constitutional checks, and limitations, and always changing easily, with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it, does, of necessity, fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible; the rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissable; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy, or despotism in some form, is all that is left….

…One section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute. The fugitive slave clause of the Constitution, and the law for the suppression of the foreign slave trade, are each as well enforced, perhaps, as any law can ever be in a community where the moral sense of the people imperfectly supports the law itself. The great body of the people abide by the dry legal obligation in both cases, and a few break over in each. This, I think, cannot be perfectly cured; and it would be worse in both cases after the separation of the sections, than before. The foreign slave trade, now imperfectly suppressed, would be ultimately revived without restriction, in one section; while fugitive slaves, now only partially surrendered, would not be surrendered at all, by the other.

Physically speaking, we cannot separate. We cannot remove our respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall between them. A husband and wife may be divorced, and go out of the presence, and beyond the reach of each other; but the different parts of our country cannot do this. They cannot but remain face to face; and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them….In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect, and defend it.”

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

CITATION: Abraham Lincoln, Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861, FULL TEXT VIA Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- When Lincoln said in his inaugural that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists,” he was quoting from himself in the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. Why did he choose to recall that line instead of his more famous (and more controversial) 1858 statement that, “A house divided against itself cannot stand”?

- In March 1861, Lincoln called secession “the essence of anarchy,” a direct enemy to what he termed “the only true sovereign of a free people.” This “sovereign” was not a mere union of states, however. Instead, according to Lincoln, the enduring American union was one between the majority and the minority. What did he mean by that critical passage?

- Lincoln described the moral argument over slavery as “the only substantial dispute” between the sections. How did Lincoln’s conviction that slavery was “wrong” inform his strategy during the secession crisis?

FURTHER READING

Douglass was infuriated by the inaugural address, the peroration in particular. Sectional reconciliation was the last thing he hoped for. –James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, p. 142

Prof. Pinsker close reading video on First Inaugural

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Presidential Inaugural Addresses (UC Santa Barbara)

- Lincoln’s First Inaugural, March 4, 1861 (Lincoln’s Writings: Multi-Media Edition)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (2007), pp. 139-143, 159-160

- Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Secession Crisis, and Ours (2022)

- VIDEO: The Autograph Book: Carlisle at War, 1861 (House Divided Project)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Caroline Eagleton, ’23

- Handout –Lincoln’s Secession Crisis