“A house divided against itself cannot stand.” I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

INTRODUCTION

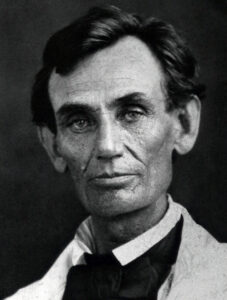

Abraham Lincoln delivered his famous “House Divided” speech on the evening of June 16, 1858, at the Illinois Republican State Convention in Springfield, Illinois. It was, in effect, an acceptance speech. Earlier that day, Illinois Republicans had adopted an unprecedented endorsement for the local attorney and former congressman as their “first and only choice” in the forthcoming campaign to unseat incumbent Senator Stephen A. Douglas. The reason why such an endorsement was unusual was because in those days there was no tradition of public campaigning for US senate seats. Before the ratification of the 17th amendment in 1912, state legislatures always selected US senators and would-be candidates typically conducted their efforts in private and after the fall legislative elections. But Lincoln’s Republican allies believed it was critical to organize an early public campaign with him as the party’s official nominee to head off growing pressure on them to support Douglas, a leading Democrat. The pressure was coming because Douglas was in the midst of a bitter feud with President James Buchanan, the more openly pro-slavery leader of his national party. To some Republicans, especially party leaders from New York, this Democratic feud represented a rare opportunity to flip an old political enemy. Yet Lincoln and the Illinois Republicans knew all too well that Douglas was not committed to their core antislavery positions –most notably their firm belief in stopping slavery’s expansion into western territories such as Kansas. That is why Lincoln used his acceptance speech on June 16 to try to explain why Douglas and his controversial doctrine of settling the fate of slavery in the territories by “popular sovereignty” or by a vote of the settlers themselves, represented a mortal threat to the future of the Republican Party and the nation itself.

SOURCE FORMAT: Public speech (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 672 words

Abraham Lincoln, Speech to the Republican state convention, June 16, 1858

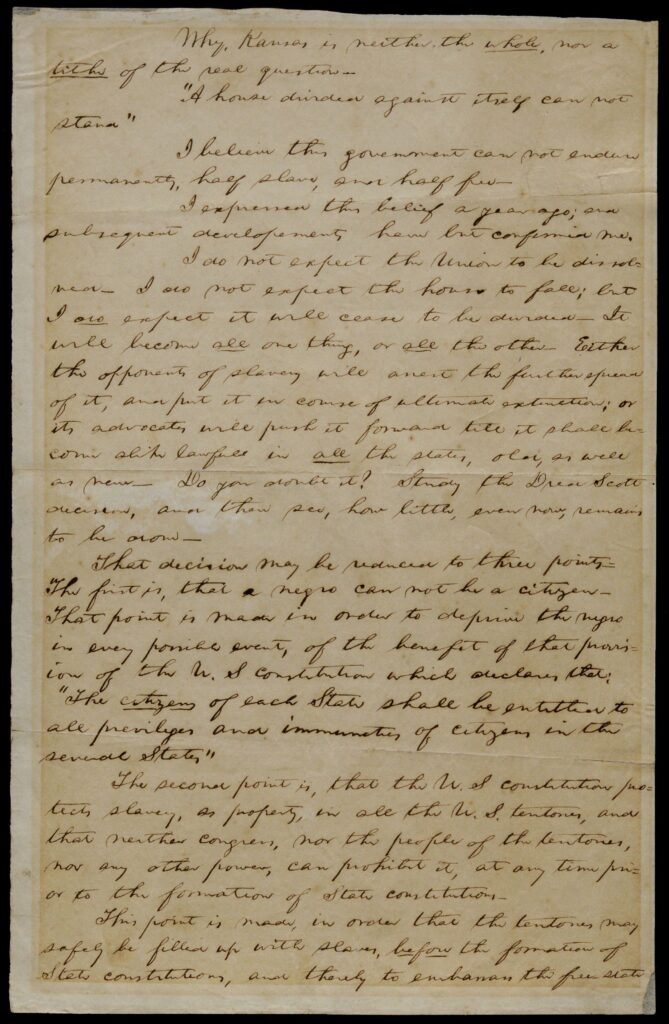

If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed.

“A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new—North as well as South.

…We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State.

To meet and overthrow the power of that dynasty, is the work now before all those who would prevent that consummation.

That is what we have to do. But how can we best do it?

There are those who denounce us openly to their own friends, and yet whisper us softly, that Senator Douglas is the aptest instrument there is, with which to effect that object. They do not tell us, nor has he told us, that he wishes any such object to be effected. They wish us to infer all, from the facts, that he now has a little quarrel with the present head of the dynasty; and that he has regularly voted with us, on a single point, upon which, he and we, have never differed.

They remind us that he is a very great man, and that the largest of us are very small ones. Let this be granted. But “a living dog is better than a dead lion.” Judge Douglas, if not a dead lion for this work, is at least a caged and toothless one. How can he oppose the advances of slavery? He don’t care anything about it. His avowed mission is impressing the “public heart” to care nothing about it….

… Now, as ever, I wish to not misrepresent Judge Douglas’ position, question his motives, or do ought that can be personally offensive to him.

Whenever, if ever, he and we can come together on principle so that our great cause may have assistance from his great ability, I hope to have interposed no adventitious obstacle.

But clearly, he is not now with us—he does not pretend to be—he does not promise to ever be.

Our cause, then, must be intrusted to, and conducted by its own undoubted friends—those whose hands are free, whose hearts are in the work—who do care for the result.

Two years ago the Republicans of the nation mustered over thirteen hundred thousand strong. We did this under the single impulse of resistance to a common danger, with every external circumstance against us. Of strange, discordant, and even, hostile elements, we gathered from the four winds, and formed and fought the battle through, under the constant hot fire of a disciplined, proud, and pampered enemy.

Did we brave all then, to falter now?—now—when that same enemy is wavering, dissevered and belligerent?

The result is not doubtful. We shall not fail—if we stand firm, we shall not fail. Wise councils may accelerate or mistakes delay it, but, sooner or later the victory is sure to come.

CITATION: Abraham Lincoln, A House Divided speech, Springfield, IL, June 16, 1858, FULL TEXT via Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Lincoln said that “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” and yet the United States had been divided over slavery for more than sixty years. What had changed to make him believe that the nation’s sectional divisions were no longer sustainable?

- Lincoln denied that he was an abolitionist like Frederick Douglass and yet here he called for the “ultimate extinction” of slavery. How radical would that prediction have seemed to various segments of the American electorate at that time?

- In 2007, when he launched his presidential bid from the Old State Capitol in Springfield, then-Senator Barack Obama quoted from this excerpt in Lincoln’s speech: “Of strange, discordant, and even, hostile elements, we gathered from the four winds, and formed and fought the battle through.” Why might an aspiring modern-day candidate like Obama have found that line so appealing?

FURTHER READING

It comes as something of a shock to see just how much vulgarity Stephen Douglas was prepared to inject into his exchanges with Abraham Lincoln. (It is almost as shocking to watch how far Lincoln was willing to descend in his unsuccessful efforts to capture the low ground from the distinguished senator.). Were those the Lincoln-Douglas debates? One of the great highlights of American political discourse? Needless to say, the debates had their better moments, especially when Lincoln moved up rather than down, ascending to some of his finest, most poetic denunciations of human slavery.” –James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, pp. xv-xvi

Prof. Matthew Pinsker offers a close-reading video segment on the House Divided speech

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Lincoln-Douglas Debates Classroom (House Divided Project)

- “House Divided Speech (June 16, 1858),” Lincoln’s Writings: The Multi-Media Edition, House Divided Project

- Clickable Word Cloud for the Lincoln-Douglas 1858 Debates

- Matthew Pinsker, “Man of Consequence: Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s,” Illinois History Teacher (2009)

- Handout –Other Lincoln-Douglass Debates