Historical documents are always a challenge for the elementary student. They love to look at the images and attempt to read the script, but when it comes right down to reading the text more often they will give up too easily feeling overwhelmed by the magnitude of the document. I recently saw an episode on television where an interviewer was asking random people on the street if they knew what important words were in the Declaration of Independence, most of the comments were funny, but all in all it was down right disturbing to watch. I would venture to say that many people just don’t know what is written in most of our historical documents that govern us today.

Using word clouds is a fun learning tool that students of all ages and abilities can use and make sense out of what they have created. Wordle is one type of word cloud tool that makes understanding a large document easier by starting out with what I call finding the “Big Words”. Students can begin by looking at the cloud images first and decide why the big words are important before they even know what document the words came from. Starting out with a challenge that gives the students instant success before tackling the more difficult is a great way of motivating them into deeper understanding. Comparing multiple word clouds is a great way to see the big picture over time. How did one document influence another? Which came first and what evidence can one find in the word cloud? Students can easily find overlapping evidence and begin to understand the importance in the big words. Small groups can then tackle the document(s) together and look for those big words and read them within the context it was written. Now what does it mean and why is it so important that these words were repeated so many times?

A few documents I had not thought to compare but did so for this blog are:

Gettysburg Address

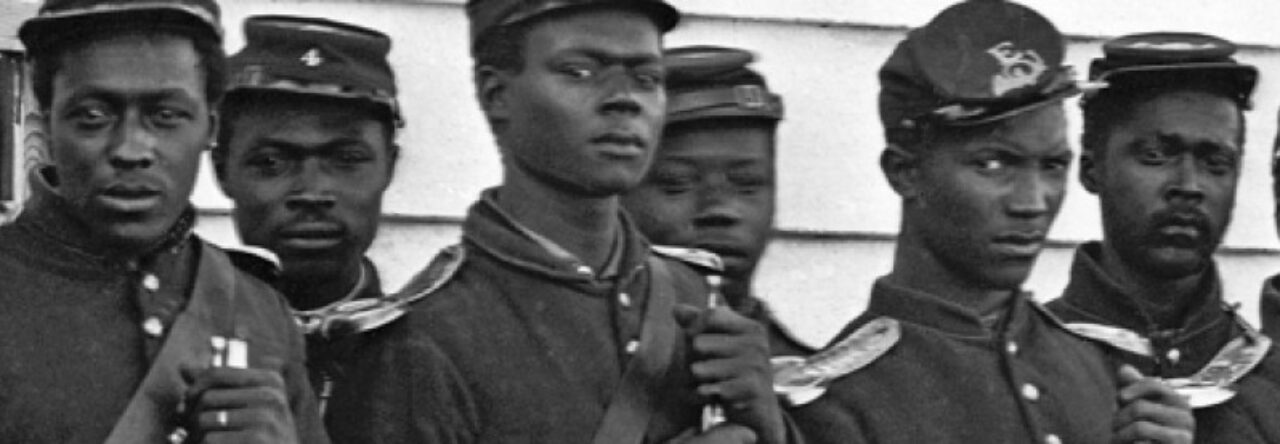

Emancipation Proclamation

Declaration of Independence

Virginia Declaration of Rights

In Virginia, elementary students begin their Virginia Studies with Jamestown 1607 and quickly travel through time to the 21st Century. By the time a 5th grade student begins to study the Civil War, they would have rapidly covered many documents. Using the word cloud tools would be a great review of the documents and help students to find the connections with each document. I myself found it interesting to compare and contrast the above four documents.

Another thought I had about the use of word clouds with historical documents would be to see if students could organize them in a timeline just based on the big words presented. Would this be beneficial in understanding the document itself or even the progression this nation has taken based on what each generation has seen as important?

Wordle, Tagxedo are excellent tools for creating word clouds. I have also used www.abcya.com/word_clouds.htm which is targeted towards K-5 students.