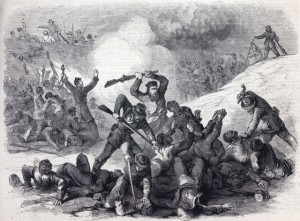

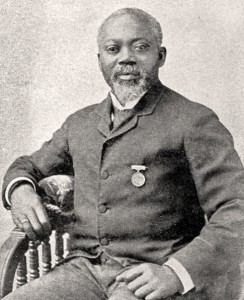

On May 31, 1897, the city of Boston erected a monument created by the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in honor of the 54th Massachusetts and its colonel, Robert Gould Shaw. The monument commemorates the regiment’s participation in the second attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. The August 8 edition of Harper’s Weekly, available in a transcribed form at Assumption College’s primary source-rich database “Northern Vision of Race, Religion & Reform” recorded that at Fort Wagner: “The 54th Massachusetts (negro), whom Copperhead officers would have called cowardly if they had stormed and carried the gates of hell, went boldly into battle, for the second time, commanded by their brave Colonel, but came out of it led by no higher officer than the boy, Lieutenant Higginson.” Sergeant James Henry Gooding of Company C of the 54th wrote weekly letters to the New Bedford Mercury, a periodical in the company’s hometown. Gooding’s letters were published as On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front, and some are available on Google Books. Gooding’s July 20 letter documents the 54th’s attack of Fort Wagner: “When the men saw their gallant leader [Colonel Shaw] fall, they made a desperate effort to get him out, but they were either shot down, or reeled in the ditch below. One man succeeded in getting hold of the State color staff.” The “one man” who reached the flag was Sergeant William H. Carney, originally of Norfolk, Virginia, as he maintained the sanctity of the flag by keeping it from touching the ground. Though Carney was wounded in both of his legs, one arm, and his chest he kept the flag aloft and is recorded as exclaiming, “the old flag never touched the ground, boys!” During the 1897 monument dedication Carney raised the flag once more, an action that Booker T. Washington recorded in his autobiography, Up from Slavery (1901), as causing such an effect on the crowd that “for a number of minutes the audience seemed to entirely lose control of itself.” Three years later, Carney received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions during the battle of Fort Wagner. Though Carney is often listed as the first African-American recipient of a Medal of Honor, instead, Carney’s rescue of the colors at Fort Wagner was the earliest African-American act of bravery to be recognized with a Medal of Honor. The medal notation reads: “Medal of Honor awarded May 9, 1900, for most dinstinguished gallantry in action at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, July 18, 1863.”

On May 31, 1897, the city of Boston erected a monument created by the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in honor of the 54th Massachusetts and its colonel, Robert Gould Shaw. The monument commemorates the regiment’s participation in the second attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. The August 8 edition of Harper’s Weekly, available in a transcribed form at Assumption College’s primary source-rich database “Northern Vision of Race, Religion & Reform” recorded that at Fort Wagner: “The 54th Massachusetts (negro), whom Copperhead officers would have called cowardly if they had stormed and carried the gates of hell, went boldly into battle, for the second time, commanded by their brave Colonel, but came out of it led by no higher officer than the boy, Lieutenant Higginson.” Sergeant James Henry Gooding of Company C of the 54th wrote weekly letters to the New Bedford Mercury, a periodical in the company’s hometown. Gooding’s letters were published as On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front, and some are available on Google Books. Gooding’s July 20 letter documents the 54th’s attack of Fort Wagner: “When the men saw their gallant leader [Colonel Shaw] fall, they made a desperate effort to get him out, but they were either shot down, or reeled in the ditch below. One man succeeded in getting hold of the State color staff.” The “one man” who reached the flag was Sergeant William H. Carney, originally of Norfolk, Virginia, as he maintained the sanctity of the flag by keeping it from touching the ground. Though Carney was wounded in both of his legs, one arm, and his chest he kept the flag aloft and is recorded as exclaiming, “the old flag never touched the ground, boys!” During the 1897 monument dedication Carney raised the flag once more, an action that Booker T. Washington recorded in his autobiography, Up from Slavery (1901), as causing such an effect on the crowd that “for a number of minutes the audience seemed to entirely lose control of itself.” Three years later, Carney received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions during the battle of Fort Wagner. Though Carney is often listed as the first African-American recipient of a Medal of Honor, instead, Carney’s rescue of the colors at Fort Wagner was the earliest African-American act of bravery to be recognized with a Medal of Honor. The medal notation reads: “Medal of Honor awarded May 9, 1900, for most dinstinguished gallantry in action at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, July 18, 1863.”

[flickrslideshow acct_name=”housedivided” id=”72157624100848401″]