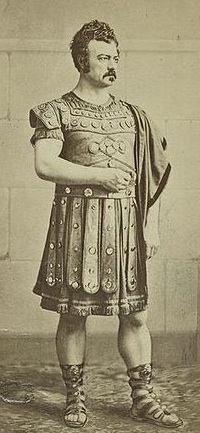

The most popular American play of the antebellum period was the historical melodrama The Gladiator (1831), by the Philadelphia physician-turned-playwright Robert Montgomery Bird (1806-1854). Bird wrote the play, but actor Edwin Forrest owned it—literally. Bird sold Forrest (1806-1872) the rights to the play for $100, and Forrest performed the title role of Spartacus to sold-out houses at least a thousand times between 1831 the end of his career four decades later.

The most popular American play of the antebellum period was the historical melodrama The Gladiator (1831), by the Philadelphia physician-turned-playwright Robert Montgomery Bird (1806-1854). Bird wrote the play, but actor Edwin Forrest owned it—literally. Bird sold Forrest (1806-1872) the rights to the play for $100, and Forrest performed the title role of Spartacus to sold-out houses at least a thousand times between 1831 the end of his career four decades later.

When he saw Forrest in the role of Spartacus in 1846, Walt Whitman wrote that the play was “as full of ‘Abolitionism’ as an egg is of meat.” Whitman continued: “It is founded on that passage of Roman history where the slaves—Gallic, Spanish, Thracian and African—rose against their masters, and formed themselves into a military organization, and for a time successfully resisted the forces sent to quell them. Running o’er with sentiments of liberty—with eloquent disclaimers of the right of the Romans to hold human beings in bondage—it is a play, this ‘Gladiator,’ calculated to make the hearts of the masses swell responsively to all those nobler manlier aspirations in behalf of mortal freedom!”

But Bird, the playwright, was no abolitionist. He was afraid of the violence abolitionism would bring down upon the nation. In his 1836 novel Sheppard Lee, for example, he portrays the institution of slavery as essentially benign, and his fictional slaves as content with their servitude until stirred to insurrection by an abolitionist pamphlet. The spectre of a slave uprising haunted him.

The Gladiator was first performed in April 1831, five months before an actual slave rebellion, under the leadership of Nat Turner, erupted in Virginia. As the news of the rebellion reached Bird, he wrote in his diary: “At this present moment there are 6[00] or 800 armed negroes marching through Southampton County, Va. murdering, ravishing & burning those whom the Grace of God has made their owners—70 killed, principally women & children. If they had but a Spartacus among them—to organize the half million of Virginia, the hundreds of thousands of the other States and to lead them on in the Crusade of Massacre, what a blessed example might they not give to the world of the excellence of slavery! What a field of interest to the playwrites of posterity! Someday we shall have it; and future generations will perhaps remember the horrors of Hayti as a farce compared with the tragedies of our own unhappy land! The vis et amor sceleratus habendi [force and criminal love of gain] will be repaid, violence with violence, & avarice with blood…”

Meanwhile, Edwin Forrest continued to pack houses with his portrayal of Spartacus. And in 1860, Matthew Brady produced a series of photographs of Forrest in costume for his most popular roles, including Spartacus. The National Portrait Gallery has a web exhibit of Brady’s photographs of Forrest. Fellow photographer Marcus Aurelius Root called them Brady’s “most remarkable productions…for artistic effect.”