The reaction to President Obama’s appearance on Between Two Ferns was swift. 32,000 viewers clicked through the video to HealthCare.gov, more than 1,000 tweeted about the segment, and health plan enrollments skyrocketed as the final deadlines approached. None of those suggestions of effectiveness, however, prevented Fox News host Bill O’Reilly from leveling a pretty tough criticism. O’Reilly was blunt and authoritative as always: “all I can tell you is Abe Lincoln wouldn’t have done it.”

The reaction to President Obama’s appearance on Between Two Ferns was swift. 32,000 viewers clicked through the video to HealthCare.gov, more than 1,000 tweeted about the segment, and health plan enrollments skyrocketed as the final deadlines approached. None of those suggestions of effectiveness, however, prevented Fox News host Bill O’Reilly from leveling a pretty tough criticism. O’Reilly was blunt and authoritative as always: “all I can tell you is Abe Lincoln wouldn’t have done it.”

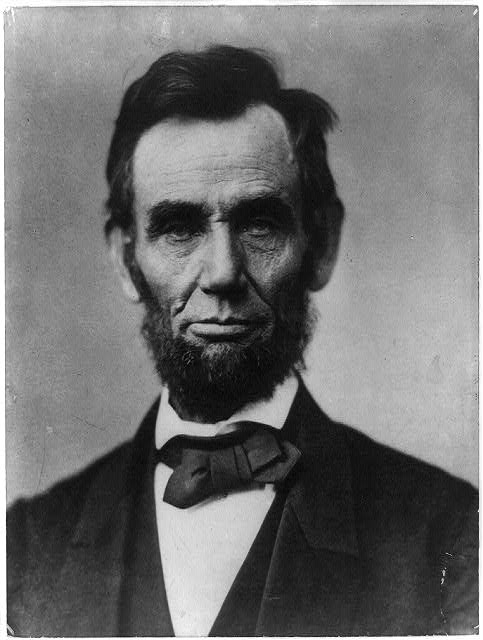

Putting aside the question of whether Abraham Lincoln really would have refused to appear on Between Two Ferns, there are a few important issues to consider when comparing President Obama’s stated goals for his unusual interview with the political experiences of President Lincoln. Those comparisons can begin with O’Reilly’s criticism itself, which actually sounds quite similar to some 19th-century commentaries about Lincoln. Ralph Waldo Emerson, writing in his diary, once accused Lincoln of “cheapening himself” as a public figure, noting that:

“He will not walk dignifiedly through the traditional part of the President of America, but will pop out his head at each railroad station and make a little speech, get into an argument with Judge A and Squire B, he will write letters to Horace Greeley, and any editor or reporter…or saucy party committee that writes to him…”

The letters Emerson was referring to – public letters – particularly rankled some 19th-century American opinion leaders. Douglas Wilson, a historian and two-time Lincoln Prize winner, notes in Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (2007), that Lincoln’s unprecedented use of public letters was viewed by some as “undignified.” Lincoln was about as compelled by that criticism then as President Obama is now. The two presidents seem to share a desire to avoid, in Obama’s words, the “Washington echo chamber.” They both sought out mediums and messages that would do just that, resonating with everyday people and conveying a highly personal touch. In attempting to quench the desire to directly connect, Obama has the internet and Lincoln had the public letter. Beginning in 1862 with his letter to Horace Greeley and continuing in 1863 with longer missives to Erastus Corning and James Conkling, Lincoln shaped popular opinion and shared his views with constituents by “corresponding” through newspapers. His messages, on slavery, emancipation, and federal power, were circulated and read widely. The Conkling letter, which we recently annotated on Poetry Genius, includes Lincoln’s famous line stating that, “there can be no appeal from the ballot to the bullet,” and employs shifts in tone and argument to convince a broad swath of the political spectrum about the wisdom of the Emancipation Proclamation. Wilson, again in Lincoln’s Sword, argues that these public letters demonstrably helped improve the president’s popularity and support for the Union cause.

A public letter to the editor of a newspaper or a political leader is a long way, however, from appearing on an internet comedy show hosted by the actor from Hangover 3. And it is worth noting that Lincoln’s public letters rarely employed humor in any substantive form. He was far from unfunny, though; in fact, in connecting with political leaders and laymen alike, Lincoln employed a similarly eclectic sense of humor that was also subject to criticism. In fact, some public figures attacked Lincoln for his humor in a way that will sound familiar to keen observers of the Between Two Ferns debate. Historian Louis Masur has a great short post (“Lincoln Tells a Story”) at the New York Times Disunion series which details both some of Lincoln’s story-telling habits and the uneven reaction. He quotes Richard Henry Dana, a prominent nineteenth-century writer and attorney, who spoke for many New Englanders when he complained during the war that Lincoln “does not act or talk or feel like the ruler of a great empire in a great crisis.” In a scholarly article titled Lincoln’s Humor: An Analysis, Benjamin Thomas fully chronicles the 16th President’s flair for pith, wit, and tall tales. The article is a treasure trove of Lincolniana, ranging from yarns and one-liners to comic biography and commentary on 19th-century humor. Thomas notes that according to Henry C. Whitney, one of Lincoln’s friends from his Illinois years, “any remark, any incident brought from [Lincoln] an appropriate tale…he saw ludicrous elements in everything.” Thomas’s analysis is instructive, at least in one sense. After all, it is hard to imagine that the man who asked whether a Nebraska river named Weeping Water was called Minneboohoo by the Indians (“because Minnehaha is Laughing Water in their language”) would not have enjoyed at least some of Two Ferns banter about strange spider bites and 800-ounce babies.

In a scholarly article titled Lincoln’s Humor: An Analysis, Benjamin Thomas fully chronicles the 16th President’s flair for pith, wit, and tall tales. The article is a treasure trove of Lincolniana, ranging from yarns and one-liners to comic biography and commentary on 19th-century humor. Thomas notes that according to Henry C. Whitney, one of Lincoln’s friends from his Illinois years, “any remark, any incident brought from [Lincoln] an appropriate tale…he saw ludicrous elements in everything.” Thomas’s analysis is instructive, at least in one sense. After all, it is hard to imagine that the man who asked whether a Nebraska river named Weeping Water was called Minneboohoo by the Indians (“because Minnehaha is Laughing Water in their language”) would not have enjoyed at least some of Two Ferns banter about strange spider bites and 800-ounce babies.

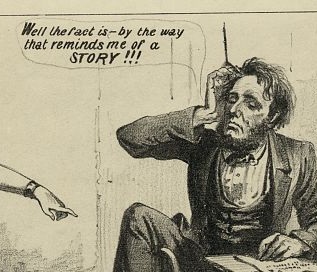

Lincoln didn’t lampoon Nebraska’s American Indian population in a public speeches or documents, though. Much of the humor Thomas describes appears to be drawn from personal interactions described in diary entries or recollections. The historian argues that after 1854, Lincoln’s public persona became more serious. O’Reilly, who has written a book on Lincoln, might have this fact in mind when he criticizes President Obama. O’Reilly could argue that as Lincoln ascended to power, he acknowledged the seriousness of the moment and changed the tone of his rhetoric. It is true that Lincoln’s rhetoric during the late 1850s and 1860s lacks some of the Springfield lawyer’s earlier folksy-funny style, but this shift did not help him shed a humorous public countenance. In the House Divided research engine, we feature several anti-Lincoln cartoons, like the one detailed above (“Columbia Demands Her Children”), which take him to task for not being serious enough (See also “Running the Machine” and “The Abolition Catastrophe” –all from the 1864 reelection campaign). These images seem to indicate that there were personal and political dimensions to Lincoln’s humor that extended well into the years of his presidency.

It is never simple to compare different moments in history, but what is at the heart of President Obama’s appearance on Between Two Ferns – the desire to connect directly to citizens and convey a persuasive message – is familiar to all who study the history of American politics. Lincoln shared President Obama’s interest in communicating directly with the American public, and doing so in a way that was original and compelling. While his humor and desire to connect with voters do not converge in his public letters, Lincoln used both humor and public correspondence in the same way that President Obama used Between Two Ferns: to develop a personal rapport with constituents, and bolster their support for a national agenda. Few things are more presidential than that.

One of the several critical strands in the “Lincoln” movie concerns the controversy surrounding the Hampton Roads peace talks (February 3, 1865), where President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward met with Confederate envoys Alexander Stephens, John Campbell and Robert M.T. Hunter for secret discussions about how to end the war on board the River Queen in Union-controlled Hampton Roads, Virginia (near Fortress Monroe). No transcript exists for their conversations that day. Lincoln and Seward died before leaving any recollection of the affair. So historians have mostly relied upon on the dubious

One of the several critical strands in the “Lincoln” movie concerns the controversy surrounding the Hampton Roads peace talks (February 3, 1865), where President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward met with Confederate envoys Alexander Stephens, John Campbell and Robert M.T. Hunter for secret discussions about how to end the war on board the River Queen in Union-controlled Hampton Roads, Virginia (near Fortress Monroe). No transcript exists for their conversations that day. Lincoln and Seward died before leaving any recollection of the affair. So historians have mostly relied upon on the dubious  According to the “Lincoln” movie script, Friday, January 27, 1865 was an action-packed and pivotal day. It was the day of Thaddeus Stevens’s controlled performance in the House, declaring himself strictly for “equality before the law.” It was also the day marked by Abraham Lincoln’s bitter argument with his oldest son Robert and then his subsequent clash with his wife Mary after he finally decided to concede to Robert’s desire to join the Union army. And it was in the evening of the 27th that both Mary Lincoln and later dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley urged the president to abandon his hidden-hand approach and provide more decisive leadership in the fight for the antislavery amendment. All of those “events” are fictional, but they are essential for understanding the film’s point-of-view –namely, that Lincoln interjected himself at the end of the battle for the constitutional amendment in a way that proved decisive.

According to the “Lincoln” movie script, Friday, January 27, 1865 was an action-packed and pivotal day. It was the day of Thaddeus Stevens’s controlled performance in the House, declaring himself strictly for “equality before the law.” It was also the day marked by Abraham Lincoln’s bitter argument with his oldest son Robert and then his subsequent clash with his wife Mary after he finally decided to concede to Robert’s desire to join the Union army. And it was in the evening of the 27th that both Mary Lincoln and later dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley urged the president to abandon his hidden-hand approach and provide more decisive leadership in the fight for the antislavery amendment. All of those “events” are fictional, but they are essential for understanding the film’s point-of-view –namely, that Lincoln interjected himself at the end of the battle for the constitutional amendment in a way that proved decisive. The filmmakers present this exchange in the most dramatic fashion possible, having Democratic leader Fernando Wood (D, NY) first disrupt the proceedings, allegedly waving “affidavits from loyal citizens” confirming the existence of secret peace talks. This creates chaos on the floor of the House that leads a fictional “conservative” Republican named Aaron Haddam to indicate (after receiving a critical nod from Preston Blair, perched in the gallery) that the “conservative faction of border and western Republicans” could not support an amendment “if a peace offer is being held hostage to its success.” Then there is a mad footrace from the Capitol to the White House, involving Lincoln’s aides and the Seward lobbyists. John Hay, the president’s young assistant private secretary, heatedly warns him against “making false representation” but Lincoln crafts his reply (technically true but obviously deceptive –since the commissioners were on their way to Hampton Roads, VA) and hands the note to seasoned lobbyist William N. Bilbo (James Spader). Bilbo then delivers it to Rep. Ashley who reads it with a flourish to the entire House. There is no record of any of this in the official proceedings. Nor does Ashley claim in his recollection that he read the note from the president on the House floor. Instead, it seems he may have simply showed it to some key figures. Bilbo was not even in Washington at the time (see previous post

The filmmakers present this exchange in the most dramatic fashion possible, having Democratic leader Fernando Wood (D, NY) first disrupt the proceedings, allegedly waving “affidavits from loyal citizens” confirming the existence of secret peace talks. This creates chaos on the floor of the House that leads a fictional “conservative” Republican named Aaron Haddam to indicate (after receiving a critical nod from Preston Blair, perched in the gallery) that the “conservative faction of border and western Republicans” could not support an amendment “if a peace offer is being held hostage to its success.” Then there is a mad footrace from the Capitol to the White House, involving Lincoln’s aides and the Seward lobbyists. John Hay, the president’s young assistant private secretary, heatedly warns him against “making false representation” but Lincoln crafts his reply (technically true but obviously deceptive –since the commissioners were on their way to Hampton Roads, VA) and hands the note to seasoned lobbyist William N. Bilbo (James Spader). Bilbo then delivers it to Rep. Ashley who reads it with a flourish to the entire House. There is no record of any of this in the official proceedings. Nor does Ashley claim in his recollection that he read the note from the president on the House floor. Instead, it seems he may have simply showed it to some key figures. Bilbo was not even in Washington at the time (see previous post  No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war.

No single film could ever hope to capture the range of historical interpretations that have been offered to explain the complicated Lincoln family dynamics. Some historians consider the marriage between Abraham and Mary Lincoln to have been “a fountain of misery.” Others see longstanding affection and partnership. Some find Lincoln to have been essentially an absentee father. Others extol his sensitive parenting toward very different sons. And these debates have proven especially difficult to resolve because the evidence is so thin. Hardly any of the family correspondence remains. None of the family members kept diaries. Almost all of our information about their relationship derives from second- or third-hand accounts, usually recollected after the war. Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in

Nor is there any basis in the historical record for intertwining the story of Robert Lincoln’s late entry into the Union army with his father’s increasingly determined efforts to secure passage of the antislavery amendment. Yet in one of the movie’s more audacious –and improbable– plot twists, scriptwriter Tony Kushner follows the explosive back-to-back family arguments of Scenes 29 and 30 with a revealing trip to the opera that suddenly provides a personal motivation for Lincoln’s new sense of urgency about the amendment’s passage. The script identifies the opera as Gounod’s “Faust” at the Odd Fellows Hall with the president, his wife and Elizabeth Keckley in attendance. In reality, the Lincolns had seen this popular opera with William Seward when it was showing at Grover’s Theater during the previous month, in  In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.

In the scene in Spielberg’s “Lincoln” which introduces the audience to Rep.  Smith

Smith Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities.

Although “Lincoln” is a serious movie with a high moral purpose, there is still a great deal of comic relief provided mostly by an amusing trio of corrupt lobbyists. What students might find confusing about these figures, however, is that despite the fact that they were “real” men, the movie either totally invents or sometimes just thoroughly rearranges their actual activities.  The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that

The main narrative of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” movie opens with a dream that  Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.

Consider this incongruity: in the movie, Seward (David Strathairn) asks Lincoln, “since when has our party unanimously supported anything?” and yet the correct historical answer to that question is simply the last time the abolition amendment appeared in the House (June 1864) when the ONLY Republican to vote against it was Rep. James Ashley, the sponsor, who did so on technical grounds so that he could bring it back later for reconsideration. By the end of the war, Republicans supported the abolition of slavery –it was a central plank of their party platform in the 1864 election and part of the basis for their landslide victories in November. Border states such as Maryland and Missouri were already in the process of abolishing slavery on their own –with full Republican support. Montgomery Blair had been “pushed out” of the president’s cabinet in September 1864 as part of a deal with radicals –as the movie suggests– but Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) surely never told Lincoln, as he does in the film: “We can’t tell our people they can vote yes on abolishing slavery unless at the same time we can tell ‘em that you’re seeking a negotiated peace.” It’s not even entirely clear that the elderly and highly controversial Blair had any “people” left in the House now that his other son Frank (Francis Preston Blair, Jr.), a former congressman, was back in the Union army.