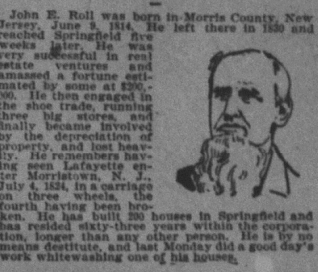

John E. Roll

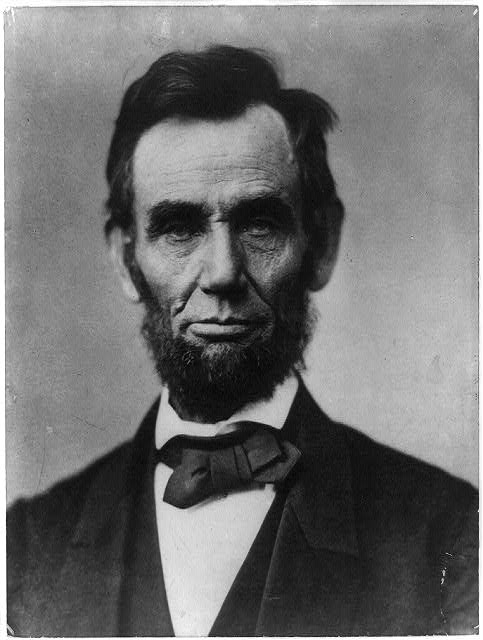

In 1895, the Chicago Times-Herald launched a series of recollected accounts about Abraham Lincoln which the editors claimed would introduce new elements to the Lincoln story. These rare recollections have never since been republished as part of their own series, but modern scholars have used some of them to powerful effect. However, this summer, student interns from the House Divided Project are busy scanning, transcribing and preparing this series for free distribution on the web. Today, we are posting just one of these recollections, an account from John E. Roll, a carpenter who knew Lincoln from New Salem days and also claimed to have heard him say during the famous “House Divided” speech (June 16, 1858), that, “I used to be a slave.” This last comment has taken on some real importance in modern years, employed in various books by some leading scholars, including Michael Burlingame and Allen Guelzo, and also, most recently, by journalist Sidney Blumenthal who is using that quotation to help open his projected four-volume biography of Lincoln. The decision raises many interesting questions about historical method, but for now, we thought it would help teachers and students to see for themselves the full transcript of Roll’s original account here. What follows below appeared in the Chicago Times-Herald on August 25, 1895 (transcribed by Trevor Diamond, Class of 2017):

John E. Roll

John E. Roll is celebrated, among other things, as having assisted Abraham Lincoln in the construction of the flat boat with which the tall Kentuckian made his first trip from Salem, Ill., to New Orleans, in 1831.

“I knew him when he was 22 years old,” said Mr. Roll. “He came down here to Sangamontown and worked in the timber building a flat boat for Orfutt & Greene, who were merchants and shippers. Sangamntown was then quite a place. There were two stores, a steam saw mill and a grist-mill, a tavern and a carding mill. I have seen fifty horses hitched there of a Saturday afternoon. Now there is not a stick to mark the place. The roads are cut out, so you can’t get to it without going across the fields.

They built the boat up there because there was better timber, and were going to take it down and load at Petersburg. Charles Broadwell had a sawmill at Sangamontown, and Lincoln was there bossing the job. I came along and wanted work, and he hired me, and I made the pins for the boat. We launched here there, and she got a good deal of water in herm and we got her down as far as Salem dam, and there she was stuck, with her bow over the dam. And Lincoln bored a hole in the bottom of the boat, and let the water out. Looks like a funny way to get water out of a boat, to bore a hole in the bottom, but if the bottom is sticking out in the air, it is all right, I guess.

Lincoln was an awful clumsy looking man at that time. He wore a homespun suit of clothes, and a big pair of cowhide boots, with his trousers strapped down under them, as was the custom of that day, to keep them from crawling up his legs. And his coat was a roundabout, and when he stooped over his work we could see about four inches of his suspenders. He had on an old slouch wool hat. He was getting $15 a month from Offutt & Greene at that time.

After we got the flatboat launched we went out in the timber and found a good tree, and made a canoe. John Seaman and Walter Carman were along and they wanted to have the first ride in the canoe, and they jumped in, and the water was very high and swift and they tipped over and were in danger of drowning. The whole bottom was overflowed and there was a big elm tree standing about 100 feet from the shore, with its branches in the water, and Lincoln called to them to swim to the tree, and hold on there till we could get them. So they caught the branches, and got up in the tree. It was in March and the water was very cold. So we got a log and tied a rope to it and James Doyle got on the log and tried to get to them but the log turned over with him and he had to get in the tree with the other two.

Then we pulled the log ashore and Lincoln got straddle of it, and the rest of us paid out the rope and let him down toward the tree, and he got to them and took them off and brought them ashore.

After that he went on and loaded his boat with corn at Petersburg, and went down the river to New Orleans. I don’t know how he got back but I have an idea he walked back though he may have come back by steamboat. He worked a while for Offutt & Greene in their store at Salem, and then he bought it out, and afterward he sold it and came here to Springfield and wen to practicing law.

All the time he was running the store he had been studying law. He would walk up here to Springfield, twenty miles, and borrow books from Major Stuart and read them, and bring them back. He didn’t seem to be much of a speaker, but it seemed he could do whatever he started to do.

I had come up here to Springfield as soon as I got through the job on the flatboat and was working at the plastering trade when he moved up here. One time I remember I saw him out here on the Salem road walking along and reading one book, with another under his arm. He got tired and sat down on a log to rest. And while he rested he went on reading.

I put my money in land as fast as I made it and was worth a good deal of money. Lincoln and I were always good friends. One time Tom Lewis and I were standing and talking on the street and Tom said: ‘John, why don’t you run for some office? You’ve got so many tenants you could make them elect you.’ And I said I didn’t want no office till Abe Lincoln was elected President of the United States, and then I would expect him to give me an office because I had worked with him on the flat boat. And Lincoln came along just then—it was long before he had ever been mentioned for President, and Tom told him what I had said. And Lincoln laughed and said when hot to be President he would give me an office.

So I was the first man he ever promised an office to, but I never got it. Oh, yes I was making more money then than any office was worth. I wouldn’t have had any office. I didn’t want any.

I remember one time in a speech he made at the courthouse, that time he said the country could not live half slave and half free, he said we were all slaves one time or another, but that white men could make themselves free and the negroes could not. He said: “There is my old friend John Roll. He used to be a slave, but he made himself free, and I used to be a slave, and now I am so free that they let me practice law.’ I remember that.”

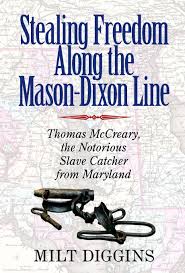

Editor’s Note: There has been an avalanche of important new scholarship on the Underground Railroad over the last twenty years, and yet there remains a critical gap in the literature. Scholars know comparatively little about the slave catchers (or kidnappers) who chased after the fugitives (or freedom seekers). This is a challenge that Maryland historian

Editor’s Note: There has been an avalanche of important new scholarship on the Underground Railroad over the last twenty years, and yet there remains a critical gap in the literature. Scholars know comparatively little about the slave catchers (or kidnappers) who chased after the fugitives (or freedom seekers). This is a challenge that Maryland historian

![1865-04-14 Garrison [?] at Sumter](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/1865-04-14-Garrison-at-Sumter-163x300.png)

![Image 3 Garrison [?] standing center](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/Image-3-Garrison-standing-center-1024x638.png)

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

The reaction to President Obama’s

The reaction to President Obama’s

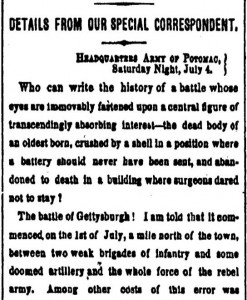

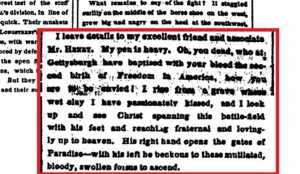

The story of the reporter,

The story of the reporter,

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.