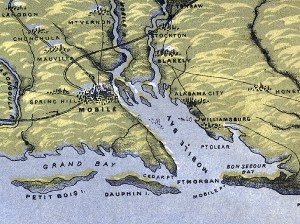

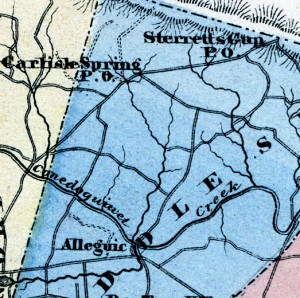

The Battle of Mobile Bay (also known as the Passing of Forts Morgan and Gaines) took place from August 2-23, 1864 in Mobile and Baldwin Counties, Alabama. In early August, a large Union fleet under the command of Admiral David G. Farragut entered Mobile Bay and came under fire from Confederate forces. Farragut led his forces past the forts and forced Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan to surrender. On August 23, Fort Morgan was the last place to fall and Mobile Bay’s port closed. The Civil War Preservation Trust’s website offers an article, “Damn the Torpedoes: The Battle of Mobile Bay,” which provides a detailed summary of the battle and its commanding officers. The website also includes a map that depicts the movement of Union and Confederate forces as well as a list of recommended readings for more information on Mobile Bay. The National Park Service’s website includes a lesson plan on Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay that includes images, readings, and maps. Foxhall Alexander Parker commented on Farragut as he and his forces crossed into Mobile Bay:

“As they were passing the Brooklyn, her captain reported ‘a heavy line of torpedoes across the channel.’ ‘Damn the torpedoes!’ was the emphatic reply of Farragut. ‘Jouett, full speed! Four bells, Captain Drayton.’ And the Hartford, as if eager to bear the admiral’s flag to the front, bounded forward ‘like a thing of life,’ and, increasing her speed at each instant, crossed both lines of torpedoes, going over the ground at the rate of nine miles an hour; for so far had she drifted to the northward and westward while her engines were stopped, as if to make it impossible for the admiral, without heading directly on to Fort Morgan, to obey his own instructions to ‘pass eastward of the easternmost buoy.’”

Another resource that may be useful is West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay, available as a preview on Google Books, which provides a detailed overview of the Battle of Mobile Bay and its significance during the Civil War. Also available on Google Books is By Sea and By River: The Naval History of the Civil War which includes details on the battle as well as the aftermath and consequences of Mobile Bay. The Civil War Trail’s website has information for those planning on visiting the battle site for a field trip as well as details on the different stops within the area and historic sites close by.