While citations are not so difficult to produce, getting the details right can be time consuming, especially for a history student looking to deliver flawless Chicago-style citations. For this reason, many students are increasingly turning to online citation-generators. There are some partially free services from commercial providers, like EasyBib or CitationMachine, and there is at least one good open-source platform called Zotero. In this post, I will explain why I believe Citation Machine is the easiest to use, especially for history students.

But first, here’s some quick background. Digital humanities faculty at George Mason University have created Zotero to be an academic, non-commercial platform for help with organizing bibliographies and citations. EasyBib and CitationMachine are actually now both owned by Chegg, a massive fee-based student tutorial service. Such commercial services have mixed reputations, though, especially among teachers, who sometimes believe that they encourage cheating and plagiarism. But few teachers object to online citation and bibliography generators. The expectations for original writing are just different. Yet most students don’t quite realize that these online generators still require significant work on the part of the student in order to get the details exactly right. You still have to edit the materials. Today, I will focus on Chegg’s CitationMachine, because it doesn’t charge anything for generating Chicago-style citations and because I do think it’s the best of all the options.

How To Use Citation Machine

- Open your web browser and go to Citation Machine for Chicago Style (Citation Machine).

- Click the type of resource you want to cite.

- Enter a link, title, or author into the search bar and search through the results for the right source. The more specific your search is, the fewer sources you will need to go through. Most likely for links, the correct page will pop up right away.

- Once you select the correct source, double check and edit the information it pulled.

- Citations automatically appear in bibliographical form. Copy and paste the citation into any platform.

- For footnotes, simply click on the “footnote” link at the bottom right corner of the citation, enter the pages you plan to use, and then copy the generated footnote and paste it in into any platform.

- Then just repeat steps 2-6 until you have cited all of your sources. Remember, however, that Citation Machine will only keep your citations for a couple days, so you can access them for a limited amount of time.

How to Use Zotero

- Open Zotero in your web browser (Zotero).

- Click the “Download” button, select “yes” to allow Zotero to make changes to your desktop, and then open Zotero when it finishes downloading. Note: if you are using a Mac, you will need to download both the 5.0 and the browser connector.

- Click the icon of the folder with a green plus mark to create a new folder and name it.

- Be sure to leave Zotero open before returning to your web browser. Zotero will not work if it is not open in the background.

- In the top right corner next to the search bar there will be a little icon of a page. Click on that icon and a little box should appear right below it.

- Click on the little downward arrow/carrot and select the folder you want the source in. You can create a tag at the bottom of the little box to find the source more easily later.

- Go back to Zotero and you can edit the information in case it did not pull all the needed information for a citation. Always double check to make sure all the information you need for a citation is present.

- Repeat steps 6-8 until you have all the sources you want.

- When you are ready to create a citation, go to the platform you are using to write in. See step 10 for Word, step 11 for Pages, step 12 for Google Docs, and step 13 for LibreOffice.

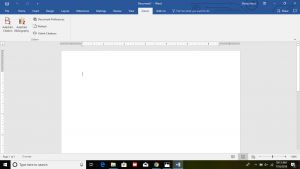

- Word is one of the easiest platforms to use Zotero with because it will automatically show up in Word as a tab at the top of the page. You will first need to install Zotero within Word. Once it is installed, click on the Zotero tab in Word and select “Add/Edit Citation” for a footnote or “Add/Edit Bibliography” for a complete bibliography that includes all the sources in the folder you select.

- There is no Zotero plugin for Pages, but it is compatible with the RTF Scan function. To use this, type the author’s name and year of publication of a source in brackets for footnotes or “Bibliography” in brackets for a bibliography. Save the document as an .RTF file and reopen Zotero. Click the tools button in Zotero and then click “RTF Scan.” Zotero should pick up your citations and insert correct Chicago Style citations so long as they are in brackets.

- The RTF Scan is also compatible with Google Docs. If you would prefer not to do the RTF Scan in Google Docs, you can place Zotero and Google Docs side-by-side and click and drag sources from Zotero to Google Docs for a bibliography. For a footnote, click on an item, press the “shift” key and drag it to Google Docs.

- Zotero offers a similar plugin to Word for LibreOffice. LibreOffice functions on Apple products, so Apple owners can access the perks of a Zotero plugin without needing to switch to a PC. Just like with Word, you will need to install the plugin in LibreOffice for Zotero before you can access it.

- You can create as many folders as you need in Zotero and reference your folders and sources whenever you need them because they are saved on your desktop.

Choosing Your Preference

Citation Gathering

Once Zotero has been installed, both Zotero and Citation Machine are equally quick to access because Zotero appears in your browser and Citation Machine opens in a tab. However, Zotero often does not pull all the information it should and it sometimes confuses the types of information, so revising the citations can be especially time consuming. Citation Machine, on the other hand, is quicker because it gathers more information and automatically converts titles that appear in caps to proper capital and lowercase letters, which Zotero does not do.

Saving Citations

One of the most helpful features of Zotero is that it can help to archive important websites and sources. This is incredibly helpful for projects that rely on multiple sources. Its inclusion of “tags” makes categorizing similar sources much easier. In addition, you can add an unlimited number of sources to each folder and can make an unlimited number of folders, so you will not lose any sources from previous projects. Citation Machine will only allow you to access sources for a few days, so you will need to save any citations you need in a document.

Cost

Both Zotero and CitationMachine are free to use, although every 48 hours in CitationMachine, you will need to watch an interactive ad for a few minutes. EasyBib actually charges an upgrade fee if you want citations generated in Chicago-style (the preferred format for most history classes). So, as long as you can put up with some ads, right now CitationMachine is the best value for the time-pressed history student.