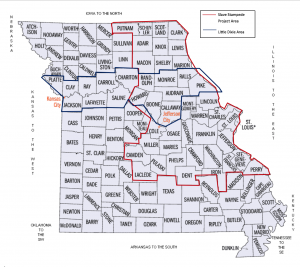

(Carlisle, Pa) During the summer of 2018, the National Park Service (NPS) and its Network to Freedom program began a cooperative agreement with the House Divided Project at Dickinson College designed to investigate the concept of “slave stampedes” with a focus on Eastern Missouri and escapes from there into the greater Missouri borderland. The goal of this research project will be to produce a full-length report  accompanied by various online resources, such as interactive maps, videos, and an underlying database of sources. We expect these freely available resources to help spark further classroom discussion and more expansive scholarly research into this national phenomenon. But beginning today (November 1, 2018), the project blog is being made available to the public. Visitors to the site will be able to see details about the project and also get real time updates on our latest research findings.

accompanied by various online resources, such as interactive maps, videos, and an underlying database of sources. We expect these freely available resources to help spark further classroom discussion and more expansive scholarly research into this national phenomenon. But beginning today (November 1, 2018), the project blog is being made available to the public. Visitors to the site will be able to see details about the project and also get real time updates on our latest research findings.

Origins and Definition. The term “slave stampede” or “stampede of slaves” began appearing in American newspapers in the late 1840s, but spread quickly during the fugitive crisis of the 1850s, and eventually became a staple of sectional debate, especially after John Brown’s raids in 1858 and 1859 and throughout the Civil War era. Participants and observers seemed to use the concept in diverse ways: sometimes to describe serial escapes by individuals or pairs, sometimes to describe either spontaneous or planned small group escapes of 3 or more people, and yet most often to define a special type of mass escape involving a dozen or more, often armed, bands of enslaved people heading defiantly toward freedom. The term thus represented for them something deeper than a vague or localized reference to group flight, but rather became weighted down with obvious revolutionary meaning. It seems clear that modern-day teachers and scholars should consider trying to situate the idea of slave stampedes more consciously within the taxonomy of American slave resistance, probably somewhere between “day-to-day resistance” and “servile insurrection.” For now, however, our research effort will define the term as broadly as possible in order to help see where the sources may lead us and to better appreciate the larger context.

Future plans. Ultimately, we anticipate a final report that explains the evolution of the slave stampede concept by detailing a number of the most important such stampedes occurring out of eastern Missouri during the late antebellum period. This Missouri borderland represents one of the most compelling places to begin studying such a phenomenon because no other slave state had a longer or more turbulent border with the free states. Consider, for example, the widely reported “slave stampede” of St. Louis-area runaways in January 1850 that seemed to travel right across former congressman Abraham Lincoln’s neighborhood in Springfield, Illinois. This story, involving a free black drayman named Jameson Jenkins who was an acquaintance of Lincoln’s, is already being interpreted at the Lincoln National Home site and offers a template for how we hope to develop other such episodes from around the region.