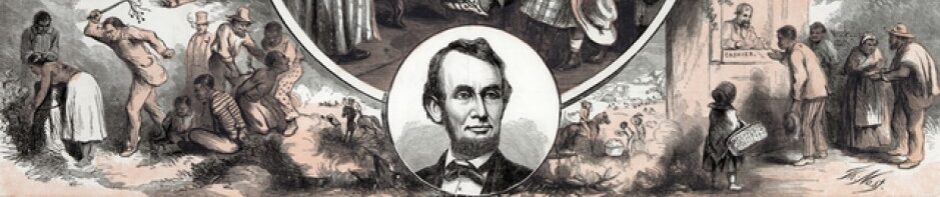

The Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863) was a pivotal document but really only one element in a dramatic and relentless struggle to abolish slavery. This classroom attempts to explain the narrative of Civil War emancipation using insights from several sources, including James Oakes’s important new book, Freedom National (Norton, 2012). Wartime emancipation began in spring 1861 with runaway slaves –the so-called “contrabands”– and then escalated as Union generals and Republican politicians experimented with different types of “confiscation” policies designed to free Confederate slaves. President Abraham Lincoln feared that confiscation was both impractical and unconstitutional as a freedom strategy and so by autumn 1862 he moved to create an emancipation policy rooted in military necessity and derived from his inherent powers as Commander in Chief. Hundreds of thousands of slaves achieved freedom under these policies and this classroom offers dozens of examples of first-hand testimony from these historical figures. Yet emancipating slaves was not the same as abolishing slavery. To really understand emancipation, you must also study abolition efforts in the District of Columbia (1862), Border States (1863-5) and through the fight in Congress for an anti-slavery Thirteenth Amendment, a story most recently brought to life by Steven Spielberg’s movie, “Lincoln” (2012). This commitment to constitutional abolition became a central issue in the 1864 election and proved to be a defining moment for President Lincoln. The president did not live to see the end of more than two centuries of legalized slavery, but he surely would have agreed with John Greenleaf Whittier’s classic poem celebrating the amendment. “It is done,” wrote Whittier proudly in “Laus Deo”. The title means simply, “Praise God.”

Credits & Contacts

Producer: Matthew Pinsker

House Divided Project

PO Box 1773 / Dickinson College

Carlisle, PA 17013

hdivided@dickinson.eduFeatured E-Book: