Had Clotel escaped from oppression in any other land, in the disguise in which she fled from the Mississippi to Richmond, and reached the United States, no honour within the gift of the American people would have been too good to have been heaped upon the heroic woman. But she was a slave, and therefore out of the pale of their sympathy.

INTRODUCTION

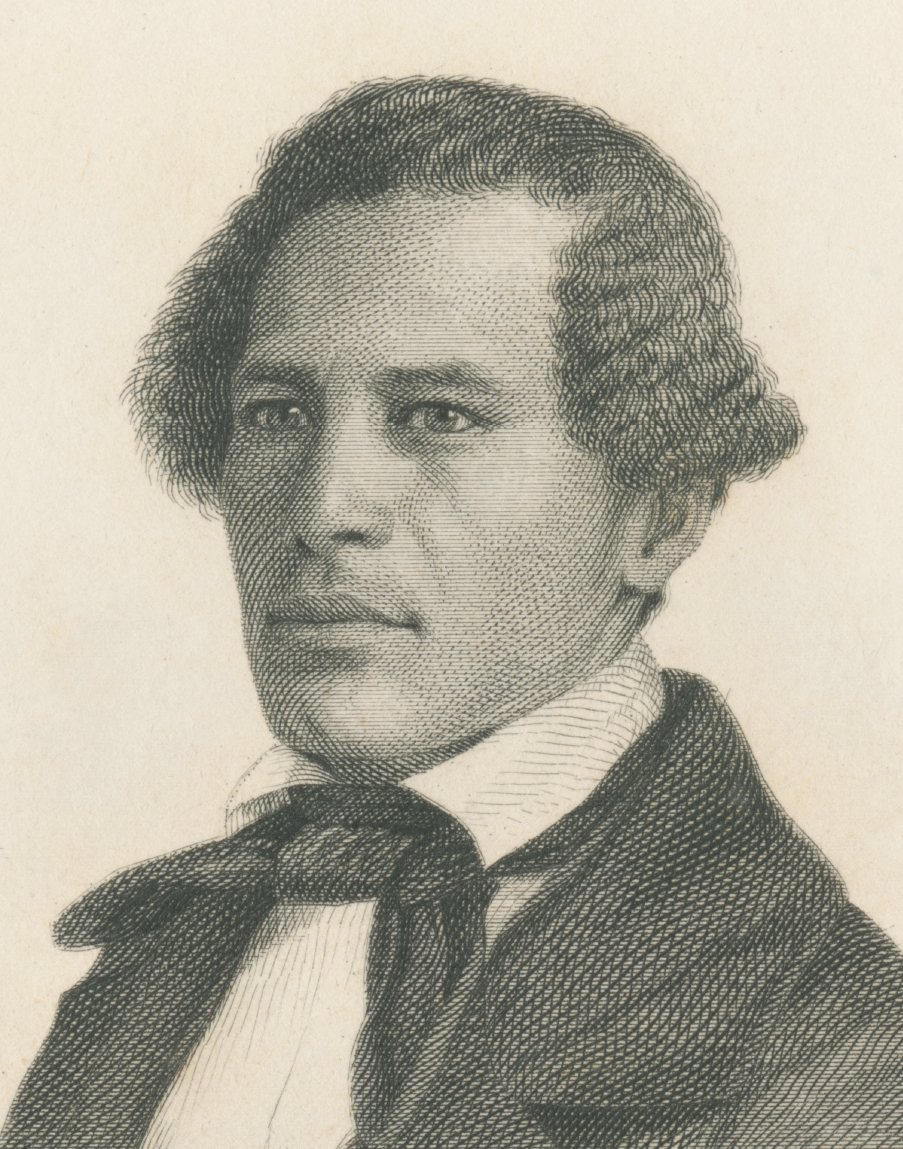

Born enslaved near Lexington, Kentucky, William Wells Brown (c. 1814-1884) ultimately became renowned for his wide-ranging antislavery writings. Although born in Kentucky, Brown spent most of his enslaved life in St. Louis, Missouri. He escaped to freedom in 1834, settling in Ohio, where he was active in the Underground Railroad, helping other runaways find freedom in Canada. Brown published a widely read account of his enslavement, entitled, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself in 1847. Then owing to concerns over his safety, Brown relocated to Great Britain, spending about five years overseas between 1849 and 1854, until British abolitionists helped purchase his freedom. During this period, Brown claimed to have delivered over a thousand antislavery lectures. This was also when he wrote, Clotel; or the President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States (1853), which was the first published novel written by an African American. The excerpt below comes from chapter 25, recounting what happened to Clotel, the enslaved fictional daughter of Thomas Jefferson, who had escaped from slavery (disguised as a white man, like Ellen Craft) but who had been captured after attempting to rescue her daughter. Clotel then committed suicide on the outskirts of Washington to avoid being recaptured by slave traders. It was what Brown imagined to be the ultimate act of antislavery resistance, or “Death is Freedom” as the chapter title suggests.

SOURCE FORMAT: Novel (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 1,314 words

CHAPTER XXV.

DEATH IS FREEDOM.

“I ASKED but freedom, and ye gave

Chains, and the freedom of the grave.”–Snelling.

THERE are, in the district of Columbia, several slave prisons, or “negro pens,” as they are termed. These prisons are mostly occupied by persons to keep their slaves in, when collecting their gangs together for the New Orleans market. Some of them belong to the government, and one, in particular, is noted for having been the place where a number of free coloured persons have been incarcerated from time to time. In this district is situated the capitol of the United States. Any free coloured persons visiting Washington, if not provided with papers asserting and proving their right to be free, may be arrested and placed in one of these dens. If they succeed in showing that they are free, they are set at liberty, provided they are able to pay the expenses of their arrest and imprisonment; if they cannot pay these expenses, they are sold out. Through this unjust and oppressive law, many persons born in the Free States have been consigned to a life of slavery on the cotton, sugar, or rice plantations of the Southern States. By order of her master, Clotel was removed from Richmond and placed in one of these prisons, to await the sailing of a vessel for New Orleans. The prison in which she was put stands midway between the capitol at Washington and the president’s house. Here the fugitive saw nothing but slaves brought in and taken out, to be placed in ships and sent away to the same part of the country to which she herself would soon be compelled to go. She had seen or heard nothing of her daughter while in Richmond, and all hope of seeing her now had fled. If she was carried back to New Orleans, she could expect no mercy from her master.

At the dusk of the evening previous to the day when she was to be sent off, as the old prison was being closed for the night, she suddenly darted past her keeper, and ran for her life. It is not a great distance from the prison to the Long Bridge, which passes from the lower part of the city across the Potomac, to the extensive forests and woodlands of the celebrated Arlington Place, occupied by that distinguished relative and descendant of the immortal Washington, Mr. George W. Curtis. Thither the poor fugitive directed her flight. So unexpected was her escape, that she had quite a number of rods the start before the keeper had secured the other prisoners, and rallied his assistants in pursuit. It was at an hour when, and in a part of the city where, horses could not be readily obtained for the chase; no bloodhounds were at hand to run down the flying woman; and for once it seemed as though there was to be a fair trial of speed and endurance between the slave and the slave-catchers. The keeper and his forces raised the hue and cry on her pathway close behind; but so rapid was the flight along the wide avenue, that the astonished citizens, as they poured forth from their dwellings to learn the cause of alarm, were only able to comprehend the nature of the case in time to fall in with the motley mass in pursuit, (as many a one did that night,) to raise an anxious prayer to heaven, as they refused to join in the pursuit, that the panting fugitive might escape, and the merciless soul dealer for once be disappointed of his prey. And now with the speed of an arrow–having passed the avenue–with the distance between her and her pursuers constantly increasing, this poor hunted female gained the “Long Bridge,” as it is called, where interruption seemed improbable, and already did her heart begin to beat high with the hope of success. She had only to pass three-fourths of a mile across the bridge, and she could bury herself in a vast forest, just at the time when the curtain of night would close around her, and protect her from the pursuit of her enemies.

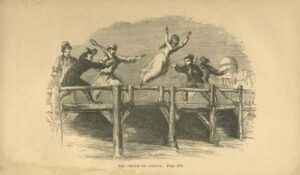

But God by his Providence had otherwise determined. He had determined that an appalling tragedy should be enacted that night, within plain sight of the President’s house and the capital of the Union, which should be an evidence wherever it should be known, of the unconquerable love of liberty the heart may inherit; as well as a fresh admonition to the slave dealer, of the cruelty and enormity of his crimes. Just as the pursuers crossed the high draw for the passage of sloops, soon after entering upon the bridge, they beheld three men slowly approaching from the Virginia side. They immediately called to them to arrest the fugitive, whom they proclaimed a runaway slave. True to their Virginian instincts as she came near, they formed in line across the narrow bridge, and prepared to seize her. Seeing escape impossible in that quarter, she stopped suddenly, and turned upon her pursuers. On came the profane and ribald crew, faster than ever, already exulting in her capture, and threatening punishment for her flight. For a moment she looked wildly and anxiously around to see if there was no hope of escape. On either hand, far down below, rolled the deep foamy waters of the Potomac, and before and behind the rapidly approaching step and noisy voices of pursuers, showing how vain would be any further effort for freedom. Her resolution was taken. She clasped her hands convulsively, and raised them, as she at the same time raised her eyes towards heaven, and begged for that mercy and compassion there, which had been denied her on earth; and then, with a single bound, she vaulted over the railings of the bridge, and sunk for ever beneath the waves of the river!

Thus died Clotel, the daughter of Thomas Jefferson, a president of the United States; a man distinguished as the author of the Declaration of American Independence, and one of the first statesmen of that country.

Had Clotel escaped from oppression in any other land, in the disguise in which she fled from the Mississippi to Richmond, and reached the United States, no honour within the gift of the American people would have been too good to have been heaped upon the heroic woman. But she was a slave, and therefore out of the pale of their sympathy. They have tears to shed over Greece and Poland; they have an abundance of sympathy for “poor Ireland;” they can furnish a ship of war to convey the Hungarian refugees from a Turkish prison to the “land of the free and home of the brave.” They boast that America is the “cradle of liberty;” if it is, I fear they have rocked the child to death. The body of Clotel was picked up from the bank of the river, where it had been washed by the strong current, a hole dug in the sand, and there deposited, without either inquest being held over it, or religious service being performed. Such was the life and such the death of a woman whose virtues and goodness of heart would have done honour to one in a higher station of life, and who, if she had been born in any other land but that of slavery, would have been honoured and loved. A few days after the death of Clotel, the following poem appeared in one of the newspapers:

“Now, rest for the wretched! the long day is past,

And night on you prison descendeth at last.

Now lock up and bolt! Ha, jailor, look there!

Who flies like a wild bird escaped from the snare?

A woman, a slave–up, out in pursuit,

While linger some gleams of day!

Let thy call ring out!–now a rabble rout

Is at thy heels–speed away!

“A bold race for freedom!–On, fugitive, on!

Heaven help but the right, and thy freedom is won.

How eager she drinks the free air of the plains;

Every limb, every nerve, every fibre she strains;

From Columbia’s glorious capitol,

Columbia’s daughter flees

To the sanctuary God has given–

The sheltering forest trees.

“Now she treads the Long Bridge–joy lighteth her eye–

Beyond her the dense wood and darkening sky–

Wild hopes thrill her heart as she neareth the shore:

O, despair! there are men fast advancing before!

Shame, shame on their manhood! they hear, they heed

The cry, her flight to stay,

And like demon forms with their outstretched arms,

They wait to seize their prey!

“She pauses, she turns! Ah, will she flee back?

Like wolves, her pursuers howl loud on their track;

She lifteth to Heaven one look of despair–

Her anguish breaks forth in one hurried prayer–

Hark! her jailor’s yell! like a bloodhound’s bay

On the low night wind it sweeps!

Now, death or the chain! to the stream she turns,

And she leaps! O God, she leaps!

“The dark and the cold, yet merciful wave,

Receives to its bosom the form of the slave;

She rises–earth’s scenes on her dim vision gleam,

Yet she struggleth not with the strong rushing stream:

And low are the death-cries her woman’s heart gives,

As she floats adown the river,

Faint and more faint grows the drowning voice,

And her cries have ceased for ever!

“Now back, jailor, back to thy dungeons, again,

To swing the red lash and rivet the chain!

The form thou would’st fetter–returned to its God;

The universe holdeth no realm of night

More drear than her slavery–

More merciless fiends than here stayed her flight–

Joy! the hunted slave is free!

“That bond woman’s corse–let Potomac’s proud wave

Go bear it along by our Washington’s grave,

And heave it high up on that hallowed strand,

To tell of the freedom he won for our land.

A weak woman’s corse, by freemen chased down;

Hurrah for our country! hurrah!

To freedom she leaped, through drowning and death–

Hurrah for our country! hurrah!”

CITATION: William Wells Brown, Clotel, Or The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States (London: Patridge & Oakey, 1853), FULL TEXT via DocSouth

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Antislavery messages came in many forms –speeches, poems, letters, ex-slave narratives, and novels. William Wells Brown was a remarkable figure who engaged in all of these forms of communication. Why might he have chosen fiction here to help convey his message about “Death is Freedom”?

- Why might Brown have considered it especially powerful to have imagined the tragic experiences of Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved daughter in this antislavery novel?

- Near the end of this chapter, Brown offered a bitter contrast between American sympathies for oppressed people in Europe and the utter lack of support for enslaved people like Clotel. Does his insight have any resonance today?

FURTHER READING

- FEATURED COLLECTION: William Wells Brown (DocSouth)

- Annette Gordon-Reed, “Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and the Ways We Talk About Our Past,” New York Times, August 24, 2017

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: TBD

- Handout –Brown, Clotel