The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line

INTRODUCTION

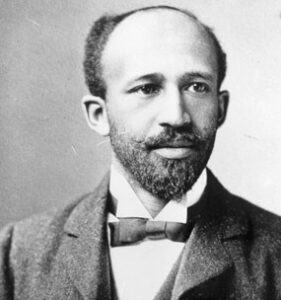

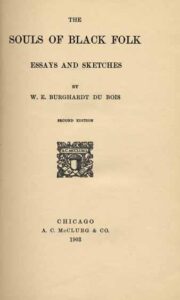

W.E.B. DuBois (1868–1963) was a famous scholar and activist who fought for civil rights for black people in both the United States and Africa. Born in Massachusetts following the Civil War, he was the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard. DuBois then became a noted academic working at several universities, and during the early twentieth century, helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which soon emerged as the nation’s premier civil rights organization. For many years, DuBois served as editor of the NAACP journal, The Crisis. He later helped expose racism in the US military and supported African nationalist in their quests for independence from European colonial powers. DuBois authored The Souls of Black Folk in 1903 when he was 35 years old. This provocative collection of essays helped establish him as a leading progressive critic of the “color line” which was still dividing Americans at the turn of the twentieth century despite the wartime destruction of slavery and the post-war constitutional promise of equality. Specifically, DuBois introduced in this work his well-known concept of “double-consciousness,” which characterized the black experience in America as one of “warring” dual identity. DuBois embraced a more radical approach to civil rights activism than some other black leaders of his time, most notably Booker T. Washington, whom he pointedly criticized in one of his more memorable essays. Students should consider, however, how this debate between radical and moderate black strategies for overcoming Jim Crow-era segregation also highlights the depth of the entrenched white resistance to integration and multi-racial democracy that endured in the decades following emancipation.

SOURCE FORMAT: Book (excerpts from Chapters 1, 2, 3, & 8)

WORD COUNT: 929 words

Excerpt from The Souls of Black Folk read by Charlotte Goodman with music by Nick Rickert:

From Chapter 1: Of Our Spiritual Strivings

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

FROM CHAPTER 2: Of the Dawn of Freedom

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line,—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea. It was a phase of this problem that caused the Civil War; and however much they who marched South and North in 1861 may have fixed on the technical points, of union and local autonomy as a shibboleth, all nevertheless knew, as we know, that the question of Negro slavery was the real cause of the conflict. Curious it was, too, how this deeper question ever forced itself to the surface despite effort and disclaimer. No sooner had Northern armies touched Southern soil than this old question, newly guised, sprang from the earth,—What shall be done with Negroes? Peremptory military commands this way and that, could not answer the query; the Emancipation Proclamation seemed but to broaden and intensify the difficulties; and the War Amendments made the Negro problems of to-day.

FROM CHAPTER 3: Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others:

Among his own people, however, Mr. Washington has encountered the strongest and most lasting opposition, amounting at times to bitterness, and even today continuing strong and insistent even though largely silenced in outward expression by the public opinion of the nation. Some of this opposition is, of course, mere envy; the disappointment of displaced demagogues and the spite of narrow minds. But aside from this, there is among educated and thoughtful colored men in all parts of the land a feeling of deep regret, sorrow, and apprehension at the wide currency and ascendancy which some of Mr. Washington’s theories have gained. These same men admire his sincerity of purpose, and are willing to forgive much to honest endeavor which is doing something worth the doing. They cooperate with Mr. Washington as far as they conscientiously can; and, indeed, it is no ordinary tribute to this man’s tact and power that, steering as he must between so many diverse interests and opinions, he so largely retains the respect of all.

But the hushing of the criticism of honest opponents is a dangerous thing. It leads some of the best of the critics to unfortunate silence and paralysis of effort, and others to burst into speech so passionately and intemperately as to lose listeners. Honest and earnest criticism from those whose interests are most nearly touched,—criticism of writers by readers,—this is the soul of democracy and the safeguard of modern society. If the best of the American Negroes receive by outer pressure a leader whom they had not recognized before, manifestly there is here a certain palpable gain. Yet there is also irreparable loss,—a loss of that peculiarly valuable education which a group receives when by search and criticism it finds and commissions its own leaders. The way in which this is done is at once the most elementary and the nicest problem of social growth. History is but the record of such group-leadership; and yet how infinitely changeful is its type and character! And of all types and kinds, what can be more instructive than the leadership of a group within a group?—that curious double movement where real progress may be negative and actual advance be relative retrogression. All this is the social student’s inspiration and despair.

From Chapter 8: Of the Quest of the Golden Fleece

We seldom study the condition of the Negro to-day honestly and carefully. It is so much easier to assume that we know it all. Or perhaps, having already reached conclusions in our own minds, we are loth to have them disturbed by facts. And yet how little we really know of these millions,—of their daily lives and longings, of their homely joys and sorrows, of their real shortcomings and the meaning of their crimes! All this we can only learn by intimate contact with the masses, and not by wholesale arguments covering millions separate in time and space, and differing widely in training and culture. To-day, then, my reader, let us turn our faces to the Black Belt of Georgia and seek simply to know the condition of the black farm-laborers of one county there.

CITATION: Excerpted from W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), FULL TEXT via Project Gutenberg

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What did DuBois mean by his discussion of how “double-consciousness” affected African Americans?

- DuBois believed that it was important for African Americans to challenge the leadership of Booker T. Washington and his theories of uplift and black self-help. Why?

- DuBois defined the main “problem” of the twentieth century as one of “the color line.” Does it remain the great problem of the twenty-first century as well?

FURTHER READING

- FEATURED COLLECTION: W.E.B. DuBois Papers (UMass)

- Jonathan Scott Holloway, “Jim Crow and the Great Migration,” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

- John P. Pittman, “Double Consciousness,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, March 21, 2016

- “The Negro Question,” New York Times, April 25, 1903

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: TBD

- Handout –DuBois Souls