This denial of all feeling against slavery, at such a time and in such circumstances, is wholly discreditable to the head and heart of Mr. LINCOLN.

INTRODUCTION

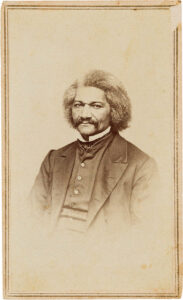

Less than ten years after his escape from slavery in 1838, Frederick Douglass had established himself as a leading abolitionist newspaper editor. He launched The North Star from his new home in Rochester, New York in 1847. This venture marked the beginning of his rupture with William Lloyd Garrison, his mentor and editor of the nation’s best-known abolitionist journal, The Liberator. In the early 1850s, Douglass merged The North Star with a Liberty Party newspaper and then renamed the venture as Frederick Douglass’s Paper. During this period, Douglass became openly aligned with the Liberty Party or the political abolitionist movement, which was led by Gerrit Smith and which opposed or tried to ignore many of Garrison’s more radical policy positions, such as pacifism and women’s rights. By mid-1860, Douglass transformed his paper into a monthly periodical, something he continued until late 1863, when abandoned the newspaper business temporarily because he thought President Lincoln was about to name him as the nation’s first black army officer. These excerpts from Douglass’s Monthly reflect his political evolution during the secession crisis. Douglass had originally supported Gerrit Smith as the Liberty Party presidential nominee in 1860, though he always seemed to recognize the importance of having the Republicans as a moderate antislavery movement. His December 1860 editorial suggests how he remained hopeful that Lincoln’s victory might ultimately break the power of the slaveholders over the nation’s future. By April 1861, following Lincoln’s inaugural address, Douglass seemed far more anxious about the new president’s commitment to their common antislavery cause. By September 1861, in a powerful rebuke of the Lincoln Administration, entitled, “Cast Off the Mill-Stone,” Douglass argued that the only way to preserve the nation was to destroy slavery –something that President Lincoln had not yet acknowledged. In the immediate aftermath of Lincoln’s decision to revoke an emancipation edict by Gen. John Fremont in Missouri, Douglass seemed especially scornful of Union efforts to placate the few remaining loyal slave or border states.

SOURCE FORMAT: Newspaper editorials

WORD COUNT: 933 words

Excerpt from Douglass’s 1861 editorial, “Cast Off the Mill-Stone,” read and produced by Caroline Eagleton, ’23

“The Late Election,” Douglass’ Monthly, December 1860

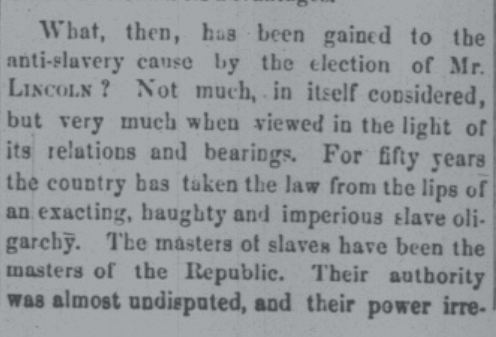

What, then, has been gained to the anti-slavery cause by the election of Mr. Lincoln? Not much, in itself considered, but very much when viewed in the light of its relations and bearings. For fifty years the country has taken the law from the lips of an exacting, haughty and imperious slave oligarchy. The masters of slaves have been masters of the Republic. Their authority was almost undisputed, and their power irresistible. They were the President makers of the Republic, and no aspirant dared to hope for success against their frown. Lincoln’s election has vitiated their authority, and broken their power. It has taught the North its strength, and shown the South its weakness. More important still, it has demonstrated the possibility of electing, if not an Abolitionist, at least an anti-slavery reputation to the Presidency of the United States. The years are few since it was thought possible that the Northern people could be wrought up to the exercise of such startling courage. Hitherto the threat of disunion has been as potent over the politicians of the North, as the cat-o’-nine-tails is over the backs of the slaves. Mr. Lincoln’s election breaks this enchantment, dispels this terrible nightmare, and awakes the nation to the consciousness of new powers, and the possibility of a higher destiny than the perpetual bondage to an ignoble fear.

–Excerpted from “The Late Election,” Douglass’ Monthly, December 1860, FULL TEXT via University of Rochester

“The Inaugural Address,” Douglass’ Monthly, April, 1861

Mr. LINCOLN opens his address by announcing his complete loyalty to slavery in the slave States, and quotes from the Chicago platform a resolution affirming the rights of property in slaves, in the slave States. He is not content with declaring that he has no lawful power to interfere with slavery in the States, but he also denies having the least ‘inclination’ to interfere with slavery in the States. This denial of all feeling against slavery, at such a time and in such circumstances, is wholly discreditable to the head and heart of Mr. LINCOLN. Aside from the inhuman coldness of the sentiment, it was a weak and inappropriate utterance to such an audience, since it could neither appease nor check the wild fury of the rebel Slave Power. Any but a blind man can see that the disunion sentiment of the South does not arise from any misapprehension of the disposition of the party represented by Mr. LINCOLN. The very opposite is the fact. The difficulty is, the slaveholders understand the position of the Republican party too well. Whatever may be the honied phrases employed by Mr. LINCOLN when confronted by actual disunion; however silvery and beautiful may be the subtle rhetoric of his long-headed Secretary of State, when wishing to hold the Government together until its management should fall into other hands; all know that the masses at the North (the power behind the throne) had determined to take and keep this Government out of the hands of the slave-holding oligarchy, and administer it hereafter to the advantage of free labor as against slave labor.

–Excerpted from “The Inaugural Address,” Douglass’ Monthly, April 1861, FULL TEXT via University of Rochester

“CAST OFF THE MILL-STONE,” Douglass’ Monthly, September, 1861

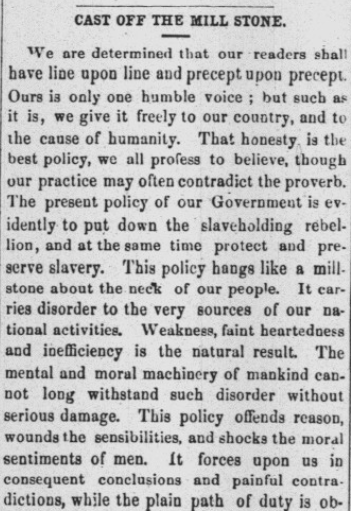

We are determined that our readers shall have line upon line and precept upon precept. Ours is only one humble voice; but such as it is, we give it freely to our country, and to the cause of humanity. That honesty is the best policy, we all profess to believe, though our practice may often contradict the proverb. The present policy of our Government is evidently to put down the slaveholding rebellion, and at the same time protect and preserve slavery. This policy hangs like a mill-stone about the neck of our people. It carries disorder to the very sources of our national activities. Weakness, faint heartedness and inefficiency is the, natural result. The mental and moral machinery of mankind cannot long withstand such disorder without serious damage. This policy offends reason, wounds the sensibilities, and shocks the moral sentiments of men. It forces upon us inconsequent conclusions and painful contradictions, while the plain path of duty is obscured and thronged with multiplying difficulties. Let us look this slavery-preserving policy squarely in the face, and search it thoroughly.

Can the friends of that policy tell us why this should not be an abolition war? Is not abolition plainly forced upon the nation as a necessity of national existence? Are not the rebels determined to make the war on their part a war for the utter destruction of liberty and the complete mastery of slavery over every other right and interest in the land? And is not an abolition war on our part the natural and logical answer to be made to the rebels? We all know it is. But it is said that for the Government to adopt the abolition policy, would involve the loss of the support of the Union men of the Border Slave States. Grant it, and what is such friendship worth? We are stronger without than with such friendship. It arms the enemy, while it disarms its friends. The fact is indisputable, that so long as slavery is respected and protected by our Government, the slaveholders can carry on the rebellion, and no longer.— Slavery is the stomach of the rebellion. The bread that feeds the rebel army, the cotton that clothes them, and the money that arms them and keeps them supplied with powder and bullets, come from the slaves, who, if consulted as to the use which should be made of their hard earnings, would say, give it to the bottom of the sea rather than do with it this mischief. Strike here, cut off the connection between the fighting master and the working slave, and you at once put an end to this rebellion, because you destroy that which feeds, clothes and arms it. Shall this not be done, because we shall offend the Union men in the Border States?

CITATION: Excerpted from “CAST OFF THE MILL-STONE,” Douglass’ Monthly, September, 1861, FULL TEXT via University of Rochester

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- According to Douglass, why did Lincoln’s election represent an important antislavery victory even though the president-elect was not a committed abolitionist?

- By September 1861, Douglass appeared frustrated over the lack of progress in the war effort. Why did he believe that the abolition of slavery was necessary for Union military victory?

FURTHER READING

From the day the new President was inaugurated Frederick Douglass worried that Lincoln would cave in to proslavery pressure, which was far more powerful than abolitionism, even in the North, by announcing a new sectional compromise. –James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, p. 159

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Secession Era Editorials (Furman)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, pp. 159-165

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Caroline Eagleton (’23)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Jake Sokolofsky (Summer 2022)

- Handout –Other Lincoln-Douglas Debates