One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.

INTRODUCTION

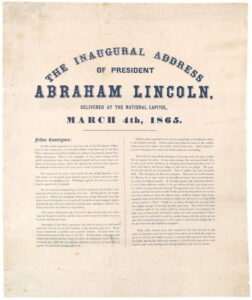

Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address from the east portico of the US Capitol building on Saturday, March 4, 1865. When Lincoln delivered his first inaugural speech in March 1861, the dome of the capitol building was still encased in scaffolding and the nation was on the precipice of disaster. Seven states had seceded from the union. The new president had little Washington experience. Everything about the country seemed unfinished and uncertain. Four years later, the scaffolding was gone, Lincoln had been reelected in a landslide, and the “slaveholding rebellion” as Frederick Douglass had called it, was nearly suppressed. Douglass happily attended Lincoln’s second inaugural, proud not only of the Union victory but also of the impending abolition of slavery. When it came to slavery, Lincoln did not mince words in this brief speech –one of the shortest inaugural addresses in American history. He said, everyone “knew” that slavery “was, somehow, the cause of the war.” More ominously, he warned Americans that they should be prepared to continue “this terrible war … until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” Yet by March 1865, the Confederacy was clearly in a state of collapse. Union armies had captured Atlanta and Savannah and were marching up the Carolinas. After months of combat and siege, General Ulysses Grant and his men were poised to take the Confederate capital of Richmond. With the end in sight, Lincoln did manage to offer the prospect of reconciliation and “malice toward none.” Yet even while invoking the spirit of “a just, and a lasting peace,” the president still urged “firmness in the right” and a national determination “to finish the work we are in.”

SOURCE FORMAT: Published speech (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 701 words

Fellow Countrymen:

At this second appearing to take the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued, seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention, and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil-war. All dreaded it—all sought to avert it. While the inaugeral address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union, and divide effects, by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.

Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully.

The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

CITATION: Abraham Lincoln, Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861, FULL TEXT via Lincoln’s Writings

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How did Lincoln cast blame for the origins of the Civil War?

- And yet how did Lincoln also share the blame for the terrible nature of the war itself?

- Was Lincoln’s Second Inaugural mainly designed to promote reconciliation (“with malice toward none”) or was it principally positioned as a statement of “firmness in the right”?

Prof. Pinsker’s close reading of Lincoln’s second inaugural (1865)

FURTHER READING

“Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass answered, “that was a sacred effort.” –quoted in James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, p. 242

Prof. David Blight (Yale) on Lincoln and Douglass in 1865

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Savior of the Union theme (Lincoln’s Writings)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (2007), pp. 238-243

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: TBD

- Handout –Second Inaugural