I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice

INTRODUCTION

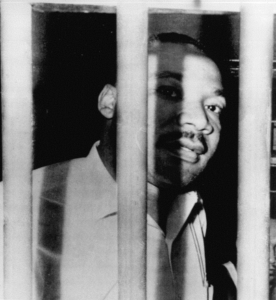

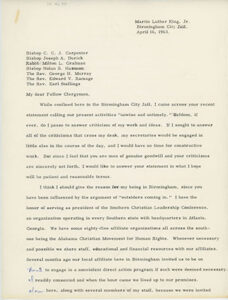

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) was a Baptist minister and world-famous civil rights activist. King grew up in Georgia, the son of a well-known pastor, graduated from Morehouse College as a teenager and then studied theology in Pennsylvania before receiving a doctorate from Boston University. He married Coretta Scott, whom he met in Boston, they started a family, and he began his ministry in Montgomery, Alabama. He became a national celebrity following his public role during the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. In 1963, King’s grassroots organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, teamed up with local civil rights groups in nearby Birmingham to initiate a protest campaign against one of the South’s most notoriously segregated cities. State and local government officials tried to stop these protests, arresting many campaign organizers. While detained in the Birmingham city jail for leading a march without a permit, King responded to criticism from eight white local clergymen who had denounced “outside” activism, while appealing for patience in what they termed, “A Call for Unity.” King’s now well-known response, dated April 16, 1963, made the case for nonviolent confrontation. King also expressed sharp disappointment with white moderates, whom he called “the Negro’s great stumbling block” in the fight for racial equality. This was not a sentiment that he repeated in his even more famous “I Have a Dream Speech” during the March on Washington just four months later. In 1964, at the age of 35, King became the youngest-ever winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was assassinated four years later in Memphis, Tennessee.

SOURCE FORMAT: Letter (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 535 words

…You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.

…We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

…I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

CITATION: Excerpted from Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963), FULL TEXT via University of Pennsylvania

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Why did King believe that “tension” was useful in his reform efforts?

- Why did King claim to fear that the “white moderate” was an even greater “obstacle” toward achieving civil rights for blacks in the 1960s than hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan?

- Today, King is better remembered for his “I have a dream” speech (August 1963) in Washington DC than for this public letter written a few months earlier in Birmingham. How might it change the way we teach and learn about his legacy if the reverse were true?

FURTHER READING

- “Birmingham Campaign,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute (Stanford University)

- “Statement by Alabama Clergymen,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute (Stanford University), April 12, 1963

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Jake Sokolofsky (Summer 2022)

- Handout –MLK Letter