“Mean, my dear? It’s rebellion! A plot—this is but the shadow of a cloud that’s fast gathering around us! I see it plainly, I see it!”

INTRODUCTION

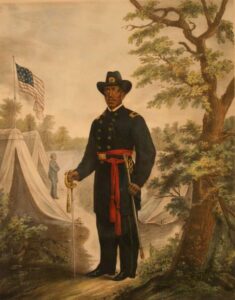

Martin Delany (1812-1885) was an influential abolitionist well-known as an editor, author, and medical doctor who became the first African American major in the United States Army. He was born in present-day West Virginia to a free mother and an enslaved father. Since Virginia was a slave state, Delany’s mother moved the family to Pennsylvania, where the family could be free. They settled near Pittsburgh where Delany received an education. In 1843, he published a newspaper called The Mystery which set the stage for Delany’s famous anti-slavery activism. In 1847, Frederick Douglass hired Delany to write for his paper, The North Star. To shed light on the cruel, racist treatment of American slaves, Delany published Blake, also known as The Huts of America, a novel serialized in The Anglo-African and Weekly Anglo-African periodicals. The novel presents the story of Henry Blake, an enslaved man who escaped from a southern plantation and traveled the world, hoping to unite the black population in a revolutionary fight against the institution of slavery. The final six chapters of the novel remain missing.

SOURCE FORMAT: Novel

WORD COUNT: 1,010 words

Chapter 7, Master and Slave

Early on Tuesday morning, in obedience to his master’s orders, Henry was on his way to the city to get the house in readiness for the reception of his mistress, Mrs. Franks having improved in three or four days. Mammy Judy had not yet risen when he knocked at the door.

“Hi Henry! yeh heah ready! huccum yeh git up so soon; arter some mischif I reckon? Do’n reckon yeh arter any good!” saluted Mammy Judy.

“No, mammy,” replied he, “no mischief, but like a good slave such as you wish me to be, come to obey my master’s will, just what you like to see.”

“Sho boy! none yeh nonsens’; huccum I want yeh bey maus Stephen? Git dat nonsens’ in yeh head las’ night long so, I reckon! Wat dat yeh gwine do now?”

“I have come to dust and air the mansion for their reception. They have sold my wife away from me, and who else would do her work?” This reply excited the apprehension of Mammy Judy.

“Wat yeh gwine do, Henry? Yeh arter no good; yeh ain’ gwine ‘tack maus Stephen, is yeh?”

“What do you mean, mammy, strike him?”

“Yes! Reckon yeh ain’ gwine hit ‘im?”

“Curse——!”

“Henry, Henry, membeh wat ye ‘fess! Fah de Laud sake, yeh ain’ gwine take to swahin?” interupted the old woman.

“I make no profession, mammy. I once did believe in religion, but now I have no confidence in it. My faith has been wrecked on the stony hearts of such pretended Christians as Stephen Franks, while passing through the stormy sea of trouble and oppression! And——”

“Hay, boy! yeh is gittin high! Yeh call maussa ‘Stephen’?”

“Yes, and I’ll never call him ‘master’ again, except when compelled to do so.”

“Bettah g’long ten’ t’ de house fo’ wite folks come, an’ nebeh mine talkin’ ’bout fightin’ ‘long wid maus Stephen. Wat yeh gwine do wid white folks? Sho!”

“I don’t intend to fight him, Mammy Judy, but I’ll attack him concerning my wife, if the words be my last! Yes, I’ll——!” and, pressing his lips to suppress the words, the outraged man turned away from the old slave mother with such feelings as only an intelligent slave could realize.

The orders of the morning were barely executed when the carriage came to the door. The bright eyes of the footboy Tony sparkled when he saw Henry approaching the carriage.

“Well, Henry! Ready for us?” enquired his master.

“Yes, sir,” was the simple reply. “Mistress!” he saluted, politely bowing as he took her hand to assist her from the carriage.

“Come, Henry my man, get out the riding horses,” ordered Franks after a little rest.

“Yes, sir.”

A horse for the Colonel and lady each was soon in readiness at the door, but none for himself, it always having been the custom in their morning rides, for the maid and manservant to accompany the mistress and master.

“Ready, did you say?” enquired Franks on seeing but two horses standing at the stile.

“Yes, sir.”

“Where’s the other horse?”

“What for, sir?”

“What for? Yourself, to be sure!”

“Colonel Franks!” said Henry, looking him sternly in the face. “When I last rode that horse in company with you and lady, my wife was at my side, and I will not now go without her! Pardon me—my life for it, I won’t go!”

“Not another word, you black imp!” exclaimed Franks, with an uplifted staff in a rage, “or I’ll strike you down in an instant!”

“Strike away if you will, sir, I don’t care—I won’t go without my wife!”

“You impudent scoundrel! I’ll soon put an end to your conduct! I’ll put you on the auction block, and sell you to the Negro-traders.”

“Just as soon as you please sir, the sooner the better, as I don’t want to live with you any longer!”

“Hold your tongue, sir, or I’ll cut it out of your head! You ungrateful black dog! Really, things have come to a pretty pass when I must take impudence off my own Negro! By gracious!—God forgive me for the expression—I’ll sell every Negro I have first! I’ll dispose of him to the hardest Negro-trader I can find!” said Franks in a rage.

“You may do your mightiest, Colonel Franks. I’m not your slave, nor never was and you know it! And but for my wife and her people, I never would have stayed with you till now. I was decoyed away when young, and then became entangled in such domestic relations as to induce me to remain with you; but now the tie is broken! I know that the odds are against me, but never mind!”

“Do you threaten me, sir! Hold your tongue, or I’ll take your life instantly, you villain!”

“No, sir, I don’ threaten you, Colonel Franks, but I do say that I won’t be treated like a dog. You sold my wife away from me, after always promising that she should be free. And more than that, you sold her because——! And now you talk about whipping me. Shoot me, sell me, or do anything else you please, but don’t lay your hands on me, as I will not suffer you to whip me!”

Running up to his chamber, Colonel Franks seized a revolver, when Mrs. Franks, grasping hold of his arm, exclaimed, “Colonel! what does all this mean?”

“Mean, my dear? It’s rebellion! A plot—this is but the shadow of a cloud that’s fast gathering around us! I see it plainly, I see it!” responded the Colonel, starting for the stairs.

“Stop, Colonel!” admonished his lady. “I hope you’ll not be rash. For Heaven’s sake, do not stain your hands in blood!”

“I do not mean to, my dear! I take this for protection!” Franks hastening down stairs, when Henry had gone into the back part of the premises.

CITATION: Martin Delany, Blake or the Huts of America (1859-61), Chapter 2, Master and Slave, FULL TEXT via University of Virginia