When we were the political slaves of King George, and wanted to be free, we called the maxim that “all men are created equal” a self evident truth; but now when we have grown fat, and have lost all dread of being slaves ourselves, we have become so greedy to be masters that we call the same maxim “a self evident lie”

INTRODUCTION

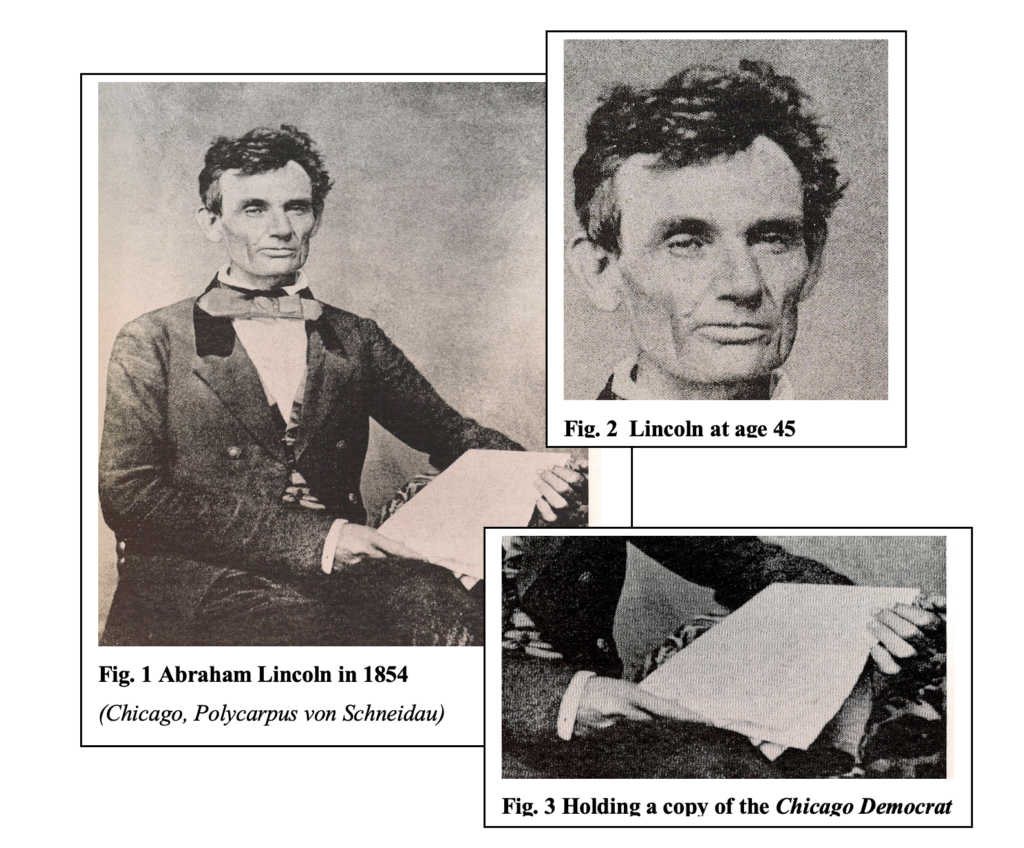

During the summer of 1855, Abraham Lincoln was a well-respected 46-year-old attorney from Springfield, Illinois, but outside of his extensive legal casework, he was also an active politician. The former congressman held no public office, but Lincoln was an acknowledged leader of the emerging Republican Party in Illinois. The new party was not calling for the immediate abolition of slavery, but it was openly antislavery. That was essentially unprecedented in American political history. No major political party had ever taken such a sectional position on such a divisive issue. Lincoln had always considered himself antislavery but his willingness to help organize and lead a sectional party was a notable departure for him. He had never before prioritized the fight against slavery in this type of fashion. These letters help illustrate both his evolution and also the challenges he faced as a moderate politician trying to organize and hold together a new antislavery coalition. The first letter, to the sister of his closest friend, described Lincoln encountering a slave coffle while he was still a young Whig politician in 1841. The second letter, written fourteen years later, responded to a visit that Lincoln had missed from a leading Kentucky conservative named Judge George Robertson, who had once helped engineer passage of the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Especially at the end of this letter, one can detect a new sense of urgency from Lincoln on the nation’s sectional crisis. In fact, Lincoln would rely on the final few sentences of this letter in 1858 when he framed his radical House Divided speech at the beginning of his senatorial campaign against Stephen A. Douglas. The other letter on this page, from August 1855, went to Joshua Speed, who had once been Lincoln’s roommate and closest friend back when they were young Whig politicians living in Springfield during the late 1830s and early 1840s. Here Lincoln cautiously addressed his own partisan evolution since that time, but he also recalled the same sad slave trading episode he had once described to Speed’s sister. In retrospect, the difference in how Lincoln related his impressions of the slave coffle seems especially revealing.

SOURCE FORMAT: Private letters

WORD COUNT: 1,600 words

Abraham Lincoln to Mary Speed, September 27, 1841 (excerpt)

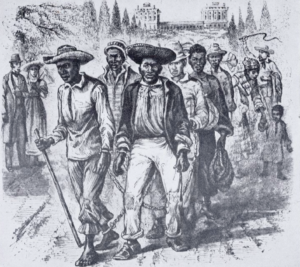

…By the way, a fine example was presented on board the boat for contemplating the effect of condition upon human happiness. A gentleman had purchased twelve negroes in different parts of Kentucky and was taking them to a farm in the South. They were chained six and six together. A small iron clevis was around the left wrist of each, and this fastened to the main chain by a shorter one at a convenient distance from, the others; so that the negroes were strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line. In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparantly happy creatures on board. One, whose offence for which he had been sold was an over-fondness for his wife, played the fiddle almost continually; and the others danced, sung, cracked jokes, and played various games with cards from day to day. How true it is that “God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,” or in other words, that He renders the worst of human conditions tolerable, while He permits the best, to be nothing better than tolerable.

Abraham Lincoln to George Robertson, August 15, 1855

Springfield, Illinois

August 15, 1855

Hon. Geo. Robertson

Lexington, Ky.

My Dear Sir: The volume you left for me has been received. I am really grateful for the honor of your kind remembrance, as well as for the book. The partial reading I have already given it, has afforded me much of both pleasure and instruction. It was new to me that the exact question which led to the Missouri compromise, had arisen before it arose in regard to Missouri; and that you had taken so prominent a part in it. Your short, but able and patriotic speech upon that occasion, has not been improved upon since, by those holding the same views; and, with all the lights you then had, the views you took appear to me as very reasonable.

You are not a friend of slavery in the abstract. In that speech you spoke of “the peaceful extinction of slavery” and used other expressions indicating your belief that the thing was, at some time, to have an end[.] Since then we have had thirty six years of experience; and this experience has demonstrated, I think, that there is no peaceful extinction of slavery in prospect for us. The signal failure of Henry Clay, and other good and great men, in 1849, to effect any thing in favor of gradual emancipation in Kentucky, together with a thousand other signs, extinguishes that hope utterly. On the question of liberty, as a principle, we are not what we have been. When we were the political slaves of King George, and wanted to be free, we called the maxim that “all men are created equal” a self evident truth; but now when we have grown fat, and have lost all dread of being slaves ourselves, we have become so greedy to be masters that we call the same maxim “a self evident lie.” The fourth of July has not quite dwindled away; it is still a great day–for burning fire-crackers!!!

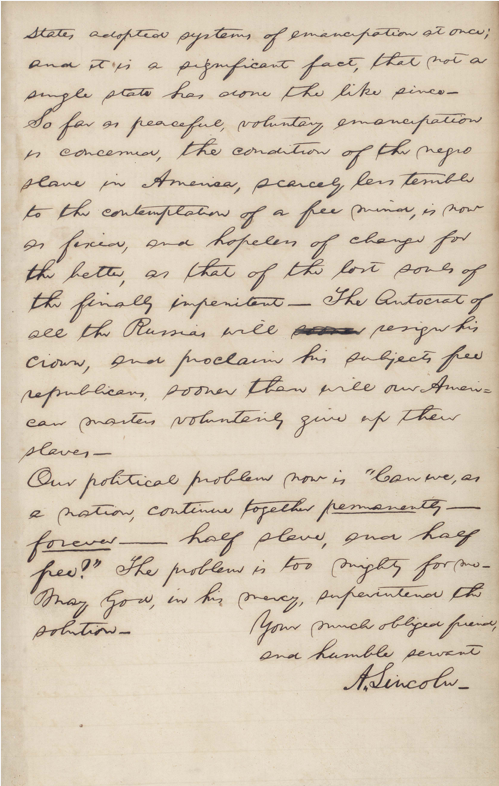

That spirit which desired the peaceful extinction of slavery, has itself become extinct, with the occasion, and the men of the Revolution. Under the impulse of that occasion, nearly half the states adopted systems of emancipation at once; and it is a significant fact, that not a single state has done the like since. So far as peaceful, voluntary emancipation is concerned, the condition of the negro

slave in America, scarcely less terrible to the contemplation of a free mind, is now as fixed, and hopeless of change for the better, as that of the lost souls of the finally impenitent. The Autocrat of all the Russias will resign his crown, and proclaim his subjects free republicans sooner than will our American masters voluntarily give up their slaves.

Our political problem now is “Can we, as a nation, continue together permanently–forever–half slave, and half free?” The problem is too mighty for me. May God, in his mercy, superintend the solution.

Your much obliged friend, and humble servant

A. Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln to Joshua Speed, August 24, 1855 (excerpt)

Springfield, Aug: 24, 1855

Dear Speed:

You know what a poor correspondent I am. Ever since I received your very agreeable letter of the 22nd. of May I have been intending to write you in answer to it. You suggest that in political action now, you and I would differ. I suppose we would; not quite as much, however, as you may think. You know I dislike slavery; and you fully admit the abstract wrong of it. So far there is no cause of difference. But you say that sooner than yield your legal right to the slave—especially at the bidding of those who are not themselves interested, you would see the Union dissolved. I am not aware that any one is bidding you to yield that right; very certainly I am not. I leave that matter entirely to yourself.

I also acknowledge your rights and my obligations, under the constitution, in regard to your slaves. I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils; but I bite my lip and keep quiet. In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a Steam Boat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border. It is hardly fair for you to assume, that I have no interest in a thing which has, and continually exercises, the power of making me miserable. You ought rather to appreciate how much the great body of the Northern people do crucify their feelings, in order to maintain their loyalty to the constitution and the Union.

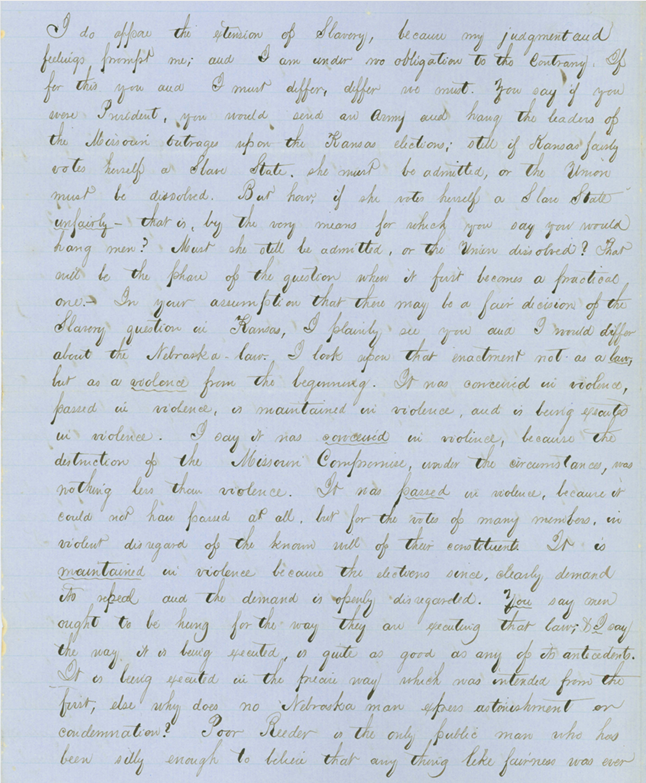

I do oppose the extension of slavery, because my judgment and feelings so prompt me; and I am under no obligation to the contrary. If for this you and I must differ, differ we must. You say if you were President, you would send an army and hang the leaders of the Missouri outrages upon the Kansas elections; still, if Kansas fairly votes herself a slave state, she must be admitted, or the Union must be dissolved. But how if she votes herself a slave state unfairly—that is, by the very means for which you say you would hang men? Must she still be admitted, or the Union be dissolved? That will be the phase of the question when it first becomes a practical one. In your assumption that there may be a fair decision of the slavery question in Kansas, I plainly see you and I would differ about the Nebraska-law.

I look upon that enactment not as a law, but as violence from the beginning. It was conceived in violence, passed in violence, is maintained in violence, and is being executed in violence. I say it was conceived in violence, because the destruction of the Missouri Compromise, under the circumstances, was nothing less than violence. It was passed in violence, because it could not have passed at all but for the votes of many members, in violent disregard of the known will of their constituents. It is maintained in violence because the elections since, clearly demand it’s repeal, and this demand is openly disregarded….The slave-breeders and slave-traders, are a small, odious and detested class, among you; and yet in politics, they dictate the course of all of you, and are as completely your masters, as you are the masters of your own negroes.

You enquire where I now stand. That is a disputed point. I think I am a whig; but others say there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist. When I was at Washington I voted for the Wilmot Proviso as good as forty times, and I never heard of any one attempting to unwhig me for that. I now do no more than oppose the extension of slavery.

I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy.

Mary will probably pass a day or two in Louisville in October. My kindest regards to Mrs. Speed. On the leading subject of this letter, I have more of her sympathy than I have of yours.

And yet let [me] say I am Your friend forever

A. LINCOLN

CITATION: Abraham Lincoln to Mary Speed, September 27, 1841; to George Robertson, August 15, 1855; to Joshua F. Speed, August 24, 1855; Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- In 1855, Lincoln remembered his encounter with a coffle of enslaved people as a source of “continual torment” for him, but in 1841, he used the episode as a way to reaffirm how Divine intervention can help make “the worst of human conditions tolerable.” What do you think explains his difference in emphasis?

- Lincoln used sarcasm in his 1855 letter to Robertson to complain about the hypocrisy of Americans celebrating the Fourth of July while so many people were enslaved in their supposedly free country. How did his antislavery anger in this letter compare and contrast to the anger of abolitionists like Frederick Douglass?

- in his letter to Joshua Speed, Lincoln brought up the subject of the Know Nothings or the growing American anti-immigrant movement. How did he try to connect the cause of the enslaved to those of immigrants? Regardless of the morality or rightness of Lincoln’s views, do you imagine that his position was a risky one politically?

FURTHER READING

Thus, by the end of the 1850s, Lincoln had become a man of “consequence” largely because of wise partisan choices. He had not held a single public office during the decade, nor had he won any fame as a military hero –the previous pathways to the presidency. What he had done time and again was to make tough, prudent choices in a confused political climate and to explain them in ways that clarified matters and held a fragile coalition together. –Matthew Pinsker, “Man of Consequence”

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Lincoln’s Writings

- FEATURED COLLECTION: NPS Underground Railroad Handbook (NEW)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (2007), pp. 61-69

- Matthew Pinsker, Man of Consequence: Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s, Illinois History Teacher (2009)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: Speed by Jonas Sherr (grad)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Peter Hass (Summer 2022)

- Handout –Lincoln to Robertson