Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.

INTRODUCTION

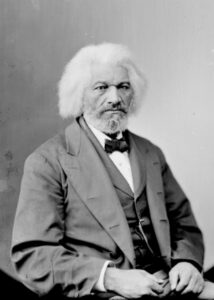

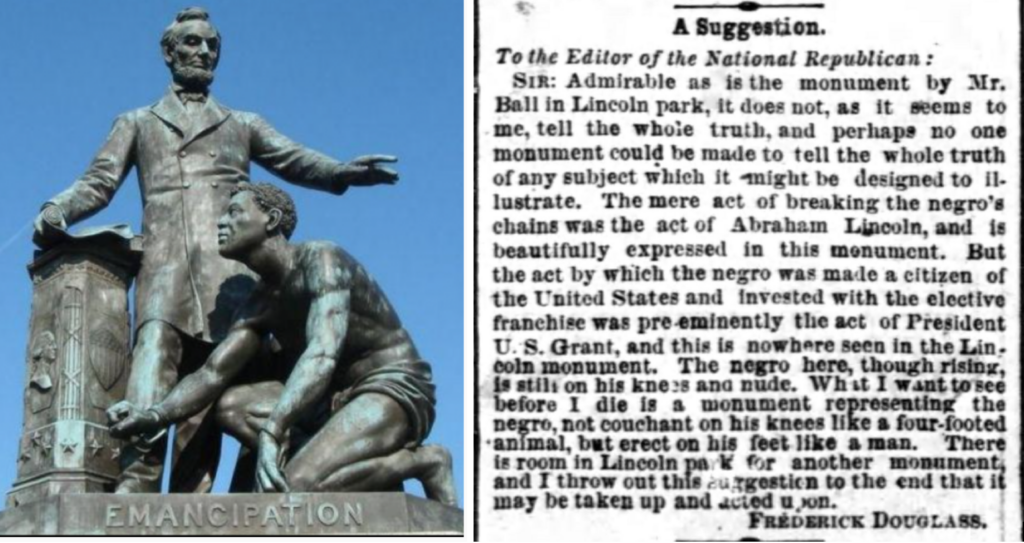

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) delivered a powerful speech in April 1876 at the dedication of the first public memorial for Abraham Lincoln in Washington, DC –a monument to his role as an emancipator paid for by contributions from ex-slaves. Douglass was then 58 years old, living in the District of Columbia with his family, and widely regarded as one of the country’s most distinguished black leaders. During the post-Civil War period, Douglass had been somewhat disappointed in his attempts to obtain high government office, but nonetheless he had received various diplomatic and political appointments, in recognition for his service to the Republican Party. By 1876, however, Douglass was deeply concerned about the rollback of civil rights as the Reconstruction period was ending. It was also a presidential election year, as well as the nation’s centennial. The stakes were high. Douglass thus used his dedication speech, on the eleventh anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination, to try to mobilize black action and to attempt to rouse greater commitment from white allies. In 1865, Douglass had famously eulogized Lincoln as “emphatically the black man’s president,” but here he remembered him as “preeminently the white man’s President.” The full speech put this depressing shift into thoughtful context, but the juxtaposition was still painfully revealing. After the ceremony, Douglass also expressed dissatisfaction with the composition of the statue, urging an additional memorial to black self-emancipation. In 2020, during the explosion of grief following George Floyd’s murder, there were multiple Black Lives Matter protests in Washington calling for the removal of the Emancipation Memorial because of its controversial composition. The statue still stands, but the debate continues.

SOURCE FORMAT: Public speech

WORD COUNT: 880 words

It must be admitted, truth compels me to admit, even here in the presence of the monument we have erected to his memory, Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.

He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country. In all his education and feeling he was an American of the Americans. He came into the Presidential chair upon one principle alone, namely, opposition to the extension of slavery. His arguments in furtherance of this policy had their motive and mainspring in his patriotic devotion to the interests of his own race. To protect, defend, and perpetuate slavery in the states where it existed Abraham Lincoln was not less ready than any other President to draw the sword of the nation. He was ready to execute all the supposed guarantees of the United States Constitution in favor of the slave system anywhere inside the slave states. He was willing to pursue, recapture, and send back the fugitive slave to his master, and to suppress a slave rising for liberty, though his guilty master were already in arms against the Government. The race to which we belong were not the special objects of his consideration. Knowing this, I concede to you, my white fellow-citizens, a preeminence in this worship at once full and supreme. First, midst, and last, you and yours were the objects of his deepest affection and his most earnest solicitude. You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his stepchildren; children by adoption, children by forces of circumstances and necessity. To you it especially belongs to sound his praises, to preserve and perpetuate his memory, to multiply his statues, to hang his pictures high upon your walls, and commend his example, for to you he was a great and glorious friend and benefactor. Instead of supplanting you at his altar, we would exhort you to build high his monuments; let them be of the most costly material, of the most cunning workmanship; let their forms be symmetrical, beautiful, and perfect; let their bases be upon solid rocks, and their summits lean against the unchanging blue, overhanging sky, and let them endure forever! But while in the abundance of your wealth, and in the fullness of your just and patriotic devotion, you do all this, we entreat you to despise not the humble offering we this day unveil to view; for while Abraham Lincoln saved for you a country, he delivered us from a bondage, according to Jefferson, one hour of which was worse than ages of the oppression your fathers rose in rebellion to oppose.

…I have said that President Lincoln was a white man, and shared the prejudices common to his countrymen towards the colored race. Looking back to his times and to the condition of his country, we are compelled to admit that this unfriendly feeling on his part may be safely set down as one element of his wonderful success in organizing the loyal American people for the tremendous conflict before them, and bringing them safely through that conflict. His great mission was to accomplish two things: first, to save his country from dismemberment and ruin; and, second, to free his country from the great crime of slavery. To do one or the other, or both, he must have the earnest sympathy and the powerful cooperation of his loyal fellow-countrymen. Without this primary and essential condition to success his efforts must have been vain and utterly fruitless. Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union, he would have inevitably driven from him a powerful class of the American people and rendered resistance to rebellion impossible. Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.

Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery. . . . The man who could say, “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war shall soon pass away, yet if God wills it continue till all the wealth piled by two hundred years of bondage shall have been wasted, and each drop of blood drawn by the lash shall have been paid for by one drawn by the sword, the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether,” gives all needed proof of his feeling on the subject of slavery. He was willing, while the South was loyal, that it should have its pound of flesh, because he thought that it was so nominated in the bond; but farther than this no earthly power could make him go.

CITATION: ORATION IN MEMORY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN, delivered at the unveiling of the Freedmen’s Monument in Memory of Abraham Lincoln, in Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., April 14, 1876, FULL TEXT via University of Rochester

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- In 1865, at a memorial service for the assassinated president, Douglass had called Lincoln “the black man’s president.” But here, in 1876 at the unveiling of the emancipation memorial, he called him “the white man’s President.” What had changed?

- Douglass clearly expressed mixed emotions about Lincoln’s leadership in this 1876 speech. Why might he have chosen to make these feeling public? What was he trying to accomplish?

- What do you think Douglass would want for the status of the DC Emancipation Memorial today if he were alive to argue about it?

FURTHER READING

- Aishvarya Kavi, “Activists Push for Removal of Statue of Freed Slave Kneeling Before Lincoln, “ New York Times, June 27, 2020

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (2007), pp. 266-275

- Jonathan W. White and Scott Sandage, “What Frederick Douglass Had to Say About Monuments,” Smithsonian, June 30, 2020

- Matthew Pinsker, “Jim Crow,” History 118: US History Since 1877, Dickinson College, Spring 2022

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: TBD

- Handout –Douglass in 1876

- Handout –Race and Reunion