I have never approved of the very public manner in which some of our western friends have conducted what they call the underground railroad, but which, I think, by their open declarations, has been made most emphatically the upperground railroad.

INTRODUCTION

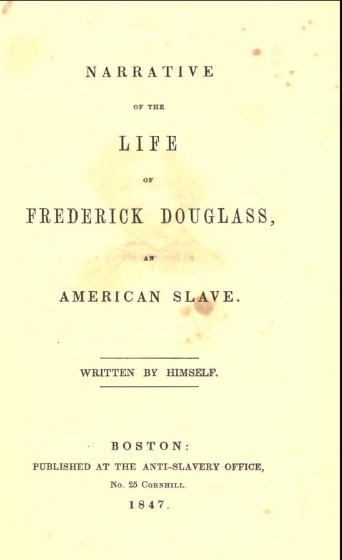

Frederick Douglas (1818-1895) was born enslaved on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. During most of his youth, Douglass was known as Frederick Bailey. From early on, Douglass was also separated from his mother, Harriet Bailey, and never really knew for certain the identity of his father, though it was always rumored to have been one of his early masters, perhaps Aaron Anthony or Thomas Auld, who was Anthony’s son-in-law. Douglass certainly had a complicated lifelong relationship with Auld, who was often cruel to him and other enslaved people, and yet with whom he maintained unusual and intermittent contact until near the end of Auld’s life in 1877. During his early years, Douglass spent time in Baltimore and on the Eastern Shore, enslaved as both a house servant and a field hand to various owners. He learned how to read in Baltimore, and famously purchased a copy of The Columbian Orator, from money he had earned after being hired out (or rented). Douglass finally escaped from slavery in 1838, with the help of a free black woman from Baltimore named Anna Murray, whom he later married in New York. Following his escape, the couple lived in Massachusetts and the newly renamed Frederick Douglass soon gained renown as an abolitionist orator embedded in the network of radical reformers and antislavery advocates gathered around controversial newspaper editor William Lloyd Garrison. In 1845, with Garrison’s support, Douglass published his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by Himself. This powerful testimony created an instant sensation and soon transformed Douglass into the nation’s best known African American leader. The excerpt below comes from Chapter 11 which detailed Douglass’s initial anxieties following his arrival in New York in September 1838. Among other concerns, Douglass was clearly worried about abolitionists in the mid-1840s who were so openly defiant about violating fugitive slave laws. And yet Douglass also went out of his way in this passage to praise David Ruggles, former head of the New York Vigilance Committee and one of the most defiant of all the Underground Railroad operatives of that era.

SOURCE FORMAT: Published memoir (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 1,600 words

CHAPTER XI.

I NOW come to that part of my life during which I planned, and finally succeeded in making, my escape from slavery. But before narrating any of the peculiar circumstances, I deem it proper to make known my intention not to state all the facts connected with the transaction….I have never approved of the very public manner in which some of our western friends have conducted what they call the underground railroad, but which, I think, by their open declarations, has been made most emphatically the upperground railroad. I honor those good men and women for their noble daring, and applaud them for willingly subjecting themselves to bloody persecution, by openly avowing their participation in the escape of slaves. I, however, can see very little good resulting from such a course, either to themselves or the slaves escaping; while, upon the other hand, I see and feel assured that those open declarations are a positive evil to the slaves remaining, who are seeking to escape. They do nothing towards enlightening the slave, whilst they do much towards enlightening the master. They stimulate him to greater watchfulness, and enhance his power to capture his slave. We owe something to the slaves south of the line as well as to those north of it; and in aiding the latter on their way to freedom, we should be careful to do nothing which would be likely to hinder the former from escaping from slavery. I would keep the merciless slaveholder profoundly ignorant of the means of flight adopted by the slave. I would leave him to imagine himself surrounded by myriads of invisible tormentors, ever ready to snatch from his infernal grasp his trembling prey. Let him be left to feel his way in the dark; let darkness commensurate with his crime hover over him; and let him feel that at every step he takes, in pursuit of the flying bondman, he is running the frightful risk of having his hot brains dashed out by an invisible agency. Let us render the tyrant no aid; let us not hold the light by which he can trace the footprints of our flying brother. But enough of this, I will now proceed to the statement of those facts, connected with my escape, for which I am alone responsible, and for which no one can be made to suffer but myself.

In the early part of the year 1838, I became quite restless. I could see no reason why I should, at the end of each week, pour the reward of my toil into the purse of my master. When I carried to him my weekly wages, he would, after counting the money, look me in the face with a robber-like fierceness, and ask, “Is this all?” He was satisfied with nothing less than the last cent. He would, however, when I made him six dollars, sometimes give me six cents, to encourage me. It had the opposite effect. I regarded it as a sort of admission of my right to the whole. The fact that he gave me any part of my wages was proof, to my mind, that he believed me entitled to the whole of them. I always felt worse for having received any thing; for I feared that the giving me a few cents would ease his conscience, and make him feel himself to be a pretty honorable sort of robber. My discontent grew upon me. I was ever on the look-out for means of escape; and, finding no direct means, I determined to try to hire my time, with a view of getting money with which to make my escape….

Things went on without very smoothly indeed, but within there was trouble. It is impossible for me to describe my feelings as the time of my contemplated start drew near. I had a number of warm-hearted friends in Baltimore,–friends that I loved almost as I did my life, –and the thought of being separated from them forever was painful beyond expression. It is my opinion that thousands would escape from slavery, who now remain, but for the strong cords of affection that bind them to their friends. The thought of leaving my friends was decidedly the most painful thought with which I had to contend. The love of them was my tender point, and shook my decision more than all things else. Besides the pain of separation, the dread and apprehension of a failure exceeded what I had experienced at my first attempt. The appalling defeat I then sustained returned to torment me. I felt assured that, if I failed in this attempt, my case would be a hopeless one–it would seat my fate as a slave forever. I could not hope to get off with any thing less than the severest punishment, and being placed beyond the means of escape. It required no very vivid imagination to depict the most frightful scenes through which I should have to pass, in case I failed. The wretchedness of slavery, and the blessedness of freedom, were perpetually before me. It was life and death with me. But I remained firm, and, according to my resolution, on the third day of September, 1838, I left my chains, and succeeded in reaching New York without the slightest interruption of any kind. How I did so,– what means I adopted,–what direction I travelled, and by what mode of conveyance,–I must leave unexplained, for the reasons before mentioned.

I have been frequently asked how I felt when I found myself in a free State. I have never been able to answer the question with any satisfaction to myself. It was a moment of the highest excitement I ever experienced. I suppose I felt as one may imagine the unarmed mariner to feel when he is rescued by a friendly man-of-war from the pursuit of a pirate. In writing to a dear friend, immediately after my arrival at New York, I said I felt like one who had escaped a den of hungry lions. This state of mind, however, very soon subsided; and I was again seized with a feeling of great insecurity and loneliness. I was yet liable to be taken back, and subjected to all the tortures of slavery. This in itself was enough to damp the ardor of my enthusiasm. But the loneliness overcame me. There I was in the midst of thousands, and yet a perfect stranger; without home and without friends, in the midst of thousands of my own brethren–children of a common Father, and yet I dared not to unfold to any one of them my sad condition. I was afraid to speak to any one for fear of speaking to the wrong one, and thereby falling into the hands of money-loving kidnappers, whose business it was to lie in wait for the panting fugitive, as the ferocious

beasts of the forest lie in wait for their prey. The motto which I adopted when I started from slavery was this–“Trust no man!” I saw in every white man an enemy, and in almost every colored man cause for distrust. It was a most painful situation; and, to understand it, one must needs experience it, or imagine himself in similar circumstances. Let him be a fugitive slave in a strange land–a land given up to be the hunting-ground for slaveholders–whose inhabitants are legalized kidnappers–where he is every moment subjected to the terrible liability of being seized upon by his fellowmen, as the hideous crocodile seizes upon his prey!– say, let him place himself in my situation–without home or friends–without money or credit–wanting shelter, and no one to give it–wanting bread, and no money to buy it,–and at the same time let him feel that he is pursued by merciless men-hunters, and in total darkness as to what to do, where to go, or where to stay,– perfectly helpless both as to the means of defence and means of escape,–in the midst of plenty, yet suffering the terrible gnawings of hunger,– in the midst of houses, yet having no home,–among fellow-men, yet feeling as if in the midst of wild beasts, whose greediness to swallow up the trembling and half-famished fugitive is only equalled by that with which the monsters of the deep swallow up the helpless fish upon which they subsist,–I say, let him be placed in this most trying situation,–the situation in which I was placed,– then, and not till then, will he fully appreciate the hardships of, and know how to sympathize with, the toil-worn and whip-scarred fugitive slave.

Thank Heaven, I remained but a short time in this distressed situation. I was relieved from it by the humane hand of Mr. DAVID RUGGLES, whose vigilance, kindness, and perseverance, I shall never forget. I am glad of an opportunity to express, as far as words can, the love and gratitude I bear him. Mr. Ruggles is now afflicted with blindness, and is himself in need of the same kind offices which he was once so forward in the performance of toward others. I had been in New York but a few days, when Mr. Ruggles sought me out, and very kindly took me to his boarding-house at the corner of Church and Lespenard Streets. Mr. Ruggles was then very deeply engaged in the memorable Darg case, as well as attending to a number of other fugitive slaves, devising ways and means for their successful escape; and, though watched and hemmed in on almost every side, he seemed to be more than a match for his enemies.

CITATION: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by Himself (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), FULL TEXT via Documenting the American South

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Why did Douglass seem so worried about what he believed was becoming “the upperground railroad” during the 1840s?

- Why didn’t Douglass feel safe after he had arrived in New York in 1838?

- Douglass expressed profound gratitude toward David Ruggles for his “vigilance, kindness, and perseverance” in assisting him during his escape. How might Douglass’s use of words in that passage have represented a kind of coded description for Underground Railroad activities?

FURTHER READING

Northern vigilance committees represented the organized core of the Underground Railroad. They acted essentially as self-protection societies located in various communities and populated mostly by black men, though their ranks also included a fair number of white men and women of all colors. –Matthew Pinsker

Biographer David Blight discusses Frederick Douglass

- FEATURED COLLECTION: NPS Underground Railroad Handbook (NEW)

- Ex-slave memoirs: North American Slave Narratives (DocSouth)

- Public letter: Frederick Douglass to Thomas Auld, September 3, 1848 (Yale)

- Erin Blakemore, “Frederick Douglass’ Emotional Meeting with the Man Who Enslaved Him,” HISTORY (2018)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (2007), pp. 8-12

- Matthew Pinsker, “Interpreting the Upper-Ground Railroad,” (2014)

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: TBD

- Handout –Douglass Escape