I end where I began—no war but an Abolition war; no peace but an Abolition peace; liberty for all, chains for none; the black man a soldier in war, a laborer in peace; a voter at the South as well as at the North; America his permanent home, and all Americans his fellow countrymen.

INTRODUCTION

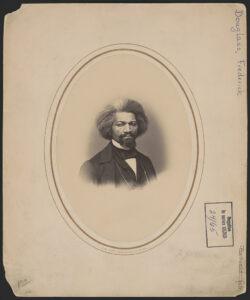

The great abolitionist orator and writer Frederick Douglass delivered this speech, “The Mission of the War,” to the Women’s Loyal National League at the Cooper Institute in New York on January 13, 1864. At that time, Douglass was about 46 years old and still hoping that President Lincoln would name him as the US Army’s first black officer. The two men had met for the first time during the previous August at the White House. “I felt big there,” Douglass had told audiences during the previous month about his encounter with the president. But Lincoln had not yet named the former antislavery newspaper editor to a military position and would, in fact, not do so before his death in April 1865. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony had founded the Women’s Loyal National League in 1863 and were preparing in early 1864 to deliver a massive series of petitions to Congress –from nearly half a million people– calling for the abolition of slavery by constitutional amendment. Douglass was a strong supporter of this abolition amendment and used his speech in New York to explain why he had always considered the Civil War to be “an abolition war,” even when some Union generals and politicians had resisted.

SOURCE FORMAT: Public speech (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 788 words

…Then there is the danger arising from the impatience of the people on account of the prolongation of the war. I know the American people. They are an impulsive people, impatient of delay, clamorous for change, and often look for results out of all proportion to the means employed in attaining them.

You and I know that the mission of this war is national regeneration. We know and consider that a nation is not born in a day. We know that large bodies move slowly—and often seem to move thus when, could we perceive their actual velocity, we should be astonished at its greatness. A great battle lost or won is easily described, understood and appreciated, but the moral growth of a great nation requires reflection, as well as observation, to appreciate it. There are vast numbers of voters, who make no account of the moral growth of a great nation and who only look at the war as a calamity to be endured only so long as they have no power to arrest it. Now, this is just the sort of people whose votes may turn the scale against us in the last event.

Thoughts of this kind tell me that there never was a time when antislavery work was more needed than now. The day that shall see the rebels at our feet, their weapons flung away, will be the day of trial. We have need to prepare for that trial. We have long been saved a proslavery peace by the stubborn, unbending persistence of the rebels. Let them bend as they will bend, there will come the test of our sternest virtues.

I have now given, very briefly, some of the grounds of danger. A word as to the ground of hope. The best that can be offered is that we have made progress—vast and striking progress—within the last two years.

President Lincoln introduced his administration to the country as one which would faithfully catch, hold and return runaway slaves to their masters. He avowed his determination to protect and defend the slaveholder’s right to plunder the black laborer of his hard earnings. Europe was assured by Mr. Seward that no slave should gain his freedom by this war. Both the President and the Secretary of State have made progress since then.

Our generals, at the beginning of the war, were horribly proslavery. They took to slave catching and slave killing like ducks to water. They are now very generally and very earnestly in favor of putting an end to slavery. Some of them, like Hunter and Butler, because they hate slavery on its own account, and others, because slavery is in arms against the government.

The rebellion has been a rapid educator. Congress was the first to respond to the instinctive judgment of the people, and fixed the broad brand of its reprobation upon slave hunting in shoulder straps. Then came very temperate talk about confiscation, which soon came to be pretty radical talk. Then came propositions for Border State, gradual, compensated, colonized emancipation. Then came the threat of a proclamation, and then came the Proclamation. Meanwhile the Negro had passed along from a loyal spade and pickax to a Springfield rifle.

Haiti and Liberia are recognized. Slavery is humbled in Maryland, threatened in Tennessee, stunned nearly to death in western Kentucky, and gradually melting away before our arms in the rebellious states.

The hour is one of hope as well as danger. But whatever may come to pass, one thing is clear: The principles involved in the contest, the necessities of both sections of the country, the obvious requirements of the age, and every suggestion of enlightened policy demand the utter extirpation of slavery from every foot of American soil, and the enfranchisement of the entire colored population of the country. Elsewhere we may find peace, but it will be a hollow and deceitful peace. Elsewhere we may find prosperity, but it will be a transient prosperity. Elsewhere we may find greatness and renown, but if these are based upon anything less substantial than justice they will vanish, for righteousness alone can permanently exalt a nation.

I end where I began—no war but an Abolition war; no peace but an Abolition peace; liberty for all, chains for none; the black man a soldier in war, a laborer in peace; a voter at the South as well as at the North; America his permanent home, and all Americans his fellow countrymen. Such, fellow citizens, is my idea of the mission of the war. If accomplished, our glory as a nation will be complete, our peace will flow like a river, and our foundation will be the everlasting rocks.

CITATION: New York Tribune, January 14, 1864, available FULL TEXT via BlackPast.org

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What did Douglass mean when he claimed that the rebellion had been “a rapid educator”?

- According to Douglass, what was the underlying mission of the war?

- How might Douglass’s hosts of the Woman’s Loyal National League have found particular resonance in his claims about the prospect of “national regeneration”?

FURTHER READING

Prof. Pinsker on women in Civil War, including the Woman’s Loyal National League

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Women’s Mobilization During Civil War (Radcliffe)

- New York Times coverage of Douglass’s 1864 speech

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: TBD

- Handout –1864 Speeches

- Handout –Debating Gettysburg Address