Action! Action! not criticism, is the plain duty of this hour. Words are now useful only as they stimulate to blows.

INTRODUCTION

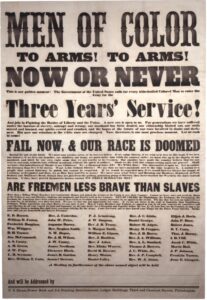

In 1863, Frederick Douglass was 45 years old and editing his newspaper, Douglass’ Monthly, from his home in Rochester, New York. During the war, the famous abolitionist had become a leading advocate for black military enlistment. in 1862, Congress authorized changes in federal law to allow for blacks in the US military. There were some experiments with all-black regiments that year, though large-scale black enlistment did not begin until after President Lincoln encouraged it as part of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Douglass delivered this speech, “Men of Color, To Arms!”, in Rochester, New York on March 2, 1863, to help mobilize African Americans toward enlistment. He urged his fellow free men of color that they had to act to help ensure the complete abolition of slavery. By the end of the Civil War, over 200,000 black men fought in the Union military..

SOURCE FORMAT: Public speech (excerpt)

WORD COUNT: 565 words

…When first the rebel cannon shattered the walls of Sumter and drove away its starving garrison, I predicted that the war then and there inaugurated would not be fought out entirely by white men. Every month’s experience during these dreary years has confirmed that opinion. A war undertaken and brazenly carried on for the perpetual enslavement of colored men, calls logically and loudly for colored men to help suppress it.

Only a moderate share of sagacity was needed to see that the arm of the slave was the best defense against the arm of the slaveholder. Hence with every reverse to the national arms, with every exulting shout of victory raised by the slaveholding rebels, I have implored the imperiled nation to unchain against her foes, her powerful black hand. Slowly and reluctantly that appeal is beginning to be heeded. Stop not now to complain that it was not heeded sooner. It may or it may not have been best that it should not.

This is not the time to discuss that question. Leave it to the future. When the war is over, the country is saved, peace is established, and the black man’s rights are secured, as they will be, history with an impartial hand will dispose of that and sundry other questions. Action! Action! not criticism, is the plain duty of this hour. Words are now useful only as they stimulate to blows. The office of speech now is only to point out when, where, and how to strike to the best advantage. There is no time to delay. The tide is at its flood that leads on to fortune. From East to West, from North to South, the sky is written all over, “Now or never.” Liberty won by white men would lose half its luster. “Who would be free themselves must strike the blow.” “Better even die free, than to live slaves.” This is the sentiment of every brave colored man amongst us.

There are weak and cowardly men in all nations. We have them amongst us. They tell you this is the “white man’s war”; that you will be “no better off after than before the war”; that the getting of you into the army is to “sacrifice you on the first opportunity.” Believe them not; cowards themselves, they do not wish to have their cowardice shamed by your brave example. Leave them to their timidity, or to whatever motive may hold them back. I have not thought lightly of the words I am now addressing you. The counsel I give comes of close observation of the great struggle now in progress, and of the deep conviction that this is your hour and mine.

In good earnest then, and after the best deliberation, I now for the first time during this war feel at liberty to call and counsel you to arms. By every consideration which binds you to your enslaved fellow-countrymen, and the peace and welfare of your country; by every aspiration which you cherish for the freedom and equality of yourselves and your children; by all the ties of blood and identity which make us one with the brave black men now fighting our battles in Louisiana and in South Carolina, I urge you to fly to arms, and smite with death the power that would bury the government and your liberty in the same hopeless grave.

CITATION: Frederick Douglass, Men of Color, To Arms, March 2, 1863, Rochester, NY

Seminar Questions

- In Douglass’s “Fifth of July” speech in 1852, he took an aggressive tone, saying “at a time like this scorching irony not convincing argument is needed.” In his “Men of Color, To Arms” speech in 1863, he took an inspiring tone, saying “there is no time to delay” and that it is “better even die free, than to live slaves.” Why did he adopt such different approaches in his language? (Alexis Varner)

- From the beginning of the war, Douglass claimed he thought the Civil War could “not be fought out entirely by white men.” Why did Douglass believe that the United States couldn’t win without the men of color? (Lea Quigley)

- In Douglass’s “Men of Color, To Arms” speech of 1863, he said that “the arm of the slave was the best defense against the arm of the slaveholder.” How did the African American experience in slavery in the South help make them the Union’s best defense against the Confederacy? (Camera Bailey)

FURTHER READING