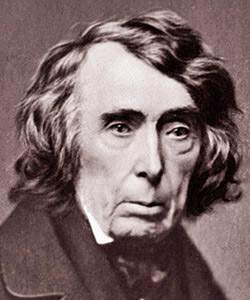

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. –Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

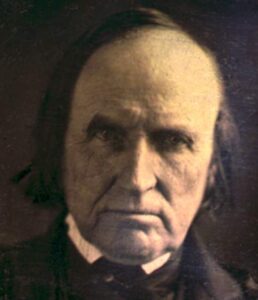

In the argument, it was said that a colored citizen would not be an agreeable member of society. This is more a matter of taste than of law. Several of the States have admitted persons of color to the right of suffrage, and in this view have recognised them as citizens; and this has been done in the slave as well as the free States. –Associate Justice John McLean

INTRODUCTION

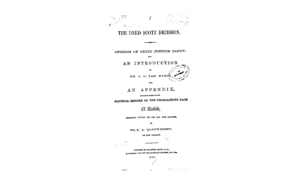

The Dred Scott case began as a set of freedom suits filed by Dred and Harriet Scott in St. Louis Circuit Court in 1846. The Scotts were parents with two young daughters, determined to protect them from the domestic slave trade. Their former slaveholder, a US Army surgeon, had taken them into free territory, and thus they had a strong case for legal liberation under what was known as the “once free, always free” doctrine. The case proceeded under Dred Scott’s name only (because of another doctrine limiting women’s rights called “coverture”). Dred Scott did win at one stage but lost his family’s case on appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court. Attorneys for Scott re-filed in federal court in 1854. The case took years, but ultimately the Taney Court reached a 7-2 verdict against Dred Scott in March 1857. Here are excerpts from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s majority opinion and a dissenting opinion by Justice John McLean. Both Taney and McLean had ties to Dickinson College.

SOURCE FORMAT: US Supreme Court opinion

WORD COUNT: 1,210 words

Excerpts from the Dred Scott decision, including from the majority opinion (Taney) and a dissent (McLean), read by Charlotte Goodman and Jordyn Ney and produced by Charlotte Goodman, ’23

From majority opinion by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (March 6, 1857)

In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in relation to that unfortunate race, which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted. But the public history of every European nation displays it in a manner too plain to be mistaken.

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever a profit could be made by it. This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing, or supposed to be open to dispute; and men in every grade and position in society daily and habitually acted upon it in their private pursuits, as well as in matters of public concern, without doubting for a moment the correctness of this opinion.

And in no nation was this opinion more firmly fixed or more uniformly acted upon than by the English Government and English people. They not only seized them on the coast of Africa, and sold them or held them in slavery for their own use; but they took them as ordinary articles of merchandise to every country where they could make a profit on them, and were far more extensively engaged in this commerce than any other nation in the world.

The opinion thus entertained and acted upon in England was naturally impressed upon the colonies they founded on this side of the Atlantic. And, accordingly, a negro of the African race was regarded by them as an article of property, and held, and bought and sold as such, in every one of the thirteen colonies which united in the Declaration of Independence, and afterwards formed the Constitution of the United States. The slaves were more or less numerous in the different colonies, as slave labor was found more or less profitable. But no one seems to have doubted the correctness of the prevailing opinion of the time.

From the dissenting opinion of Associate Justice John McLean (March 7, 1857)

The pleader has not the boldness to allege that the plaintiff is a slave, as that would assume against him the matter in controversy, and embrace the entire merits of the case in a plea to the jurisdiction. But beyond the facts set out in the plea, the court, to sustain it, must assume the plaintiff to be a slave, which is decisive on the merits. This is a short and an effectual mode of deciding the cause; but I am yet to learn that it is sanctioned by any known rule of pleading.

The defendant’s counsel complain, that if the court take jurisdiction on the ground that the plaintiff is free, the assumption is against the right of the master. This argument is easily answered. In the first place, the plea does not show him to be a slave; it does not follow that a man is not free whose ancestors were slaves. The reports of the Supreme Court of Missouri show that this assumption has many exceptions; and there is no averment in the plea that the plaintiff is not within them.

By all the rules of pleading, this is a fatal defect in the plea. If there be doubt, what rule of construction has been established in the slave States? In Jacob v. Sharp, (Meigs’s Rep., Tennessee, 114,) the court held, when there was doubt as to the constuction of a will which emancipated a slave, ‘it must be construed to be subordinate to the higher and more important right of freedom.’

No injustice can result to the master, from an exercise of jurisdiction in this cause. Such a decision does not in any degree affect the merits of the case; it only enables the plaintiff to assert his claims to freedom before this tribunal. If the jurisdiction be ruled against him, on the ground that he is a slave, it is decisive of his fate.

It has been argued that, if a colored person be made a citizen of a State, he cannot sue in the Federal court. The Constitution declares that Federal jurisdiction ‘may be exercised between citizens of different States,’ and the same is provided in the act of 1789. The above argument is properly met by saying that the Constitution was intended to be a practical instrument; and where its language is too plain to be misunderstood, the argument ends.’

In Chirae v. Chirae, (2 Wheat., 261; 4 Curtis, 99,) this court says: ‘That the power of naturalization is exclusively in Congress does not seem to be, and certainly ought not to be, controverted.’ No person can legally be made a citizen of a State, and consequently a citizen of the United States, of foreign birth, unless he be naturalized under the acts of Congress. Congress has power ‘to establish a uniform rule of naturalization.’

It is a power which belongs exclusively to Congress, as intimately connected with our Federal relations. A State may authorize foreigners to hold real estate within its jurisdiction, but it has no power to naturalize foreigners, and give them the rights of citizens. Such a right is opposed to the acts of Congress on the subject of naturalization, and subversive of the Federal powers. I regret that any countenance should be given from this bench to a practice like this in some of the States, which has no warrant in the Constitution.

In the argument, it was said that a colored citizen would not be an agreeable member of society. This is more a matter of taste than of law. Several of the States have admitted persons of color to the right of suffrage, and in this view have recognised them as citizens; and this has been done in the slave as well as the free States. On the question of citizenship, it must be admitted that we have not been very fastidious. Under the late treaty with Mexico, we have made citizens of all grades, combinations, and colors. The same was done in the admission of Louisiana and Florida. No one ever doubted, and no court ever held, that the people of these Territories did not become citizens under the treaty. They have exercised all the rights of citizens, without being naturalized under the acts of Congress.

CITATION: Dred Scott v. John F.A. Sandford (1857) 60 U.S. 393 with FULL TEXT available via Legal Information Institute (Cornell)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- When Chief Justice Taney wrote that American blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” he was not describing present conditions in 1857 but rather the hundred years leading up to the American Revolution. He was doing this so he could explain (and in his mind, restore) the original intent of the Framers. But could Taney have seriously believed that blacks were gaining rights between 1776 and 1857?

- How was Justice McLean trying to point out contradictions or complications in Taney’s version of America’s racial history?

- Why is it important to remember the entire Scott family and not just the named litigant, Dred Scott?

FURTHER READING

- FEATURED COLLECTION: Dred Scott Case Collection (Washington U)

- Dred Scott Case And Its Bitter Legacy, Gilder Lehrman Institute and House Divided Project (Google Arts, 2008)

- Coming of the War, Civil War & Reconstruction Online, House Divided Project (2015-21)

- James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (2007), pp. 73-81

- STUDENT CLOSE READING: By Charlotte Goodman (’23)

- Handout –Dred and Harriet Scott