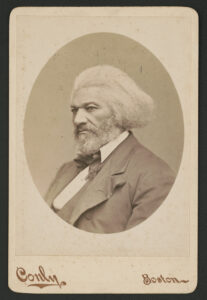

“Cast off the Millstone” — Frederick Douglass (1861)

By Jake Sokolofsky (Summer 2022)

President Lincoln from the start of the Civil War had endorsed the idea that slavery would not be challenged where it existed, but Frederick Douglass knew the war was fundamentally being fought over slavery [1]. Trying to avoid further Southern secession at all costs to keep open the possibility of reconciliation, the Lincoln administration chiefly used their policy of appeasement toward slavery to avoid alienating the border states of Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware [2]. Douglass, however, was appalled at this idea. He took to his Douglass’ Monthly to express his dissatisfaction, a paper with a readership of mostly sympathetic Northerners in New York, itself a hotbed of abolition and radicalism. Commenting on a policy he saw as willfully ignorant and ensuring slavery’s perpetuation, Douglass wrote a searing critique of appeasement as part of a larger critique of slavery. Douglass’s editorial “Cast off the Millstone,” though on the surface arguing solely against a specific policy, used the metaphor of the millstone and its Biblical origins to touch on more fundamental issues of slavery’s power and delineate a path forward.

Much like his other famous writings and speeches, Douglass in his editorial evoked religious doctrine to appeal to his listener’s dispositions and argue against slavery and slaveholders’ hypocrisies. The “mill-stone” in the title of the editorial is a specific Biblical reference to Matthew 18:6:

If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.

A divine form of capital punishment, Douglass described the policy of preserving slavery as a “millstone around the neck of our people,” a weight so heavy as to crush all life and future out of the wearer [3]. Among his abolitionist, educated Northern audience in New York, this reference to the millstone and Bible would buttress his critique as a manifestation of true Biblical morality through his abolitionist value system. The millstone in this case gives a word to a principle Douglass had long spoken on: slavery and the life of Black America were intricately intertwined in opposition, and one must be eradicated or the other will be.

The chief target of Douglass’s millstone analogy was what he deemed the “border state compromise,” an effort by Lincoln at the beginning of the secession crisis to keep the border states in the Union to avoid a war that the North could not win; if they seceded, the balance of power may have tipped towards the Confederacy. The border states also supplied crucial railroads, supply lines, and materials that would give either side a significant advantage [4]. As such, Lincoln had to tread carefully: too bold a threat to slavery might enrage the slave-holding sympathies in the border states states, but he needed to emphasize that slavery must end in some way. Lincoln’s political savviness kept him from any radical policies but in the meantime generated vicious critique from more radical antislavery forces.

Though Lincoln’s critical attitude towards slavery was already enough cause for concern to many, Douglass was not convinced nor pleased with Lincoln’s pronouncements. According to Douglass, the policy of suppressing the rebellion but protecting slavery where it existed was a millstone, a force creating disorder and “painful contradictions” regarding the founding ideas of American democracy. To Douglass, the only way to truly win the war was to make it an abolition war because “the masters of slaves have been the masters of the Republic”; in essence, eradicating the cause of the millstone’s placement [5]. As Douglass argued, “so long as slavery is respected and protected by our Government, the slaveholders can carry on the rebellion,” a position he maintained throughout the war and one that moderates like Lincoln slowly moved towards. The compromises of the millstone were a force that could end the future of Black America through continuing the rebellion, thus opposing any goals of future unity of anti-slavery.

Though outwardly describing only the border crisis, Douglass embarked on a broader critique of slavery and its power again using the metaphor. Slaveholders could materially and ideologically carry on the rebellion because it was the “stomach of the rebellion” to Douglass, providing “the bread that feeds the rebel army, the cotton that clothes them, and the money that arms them and keeps them supplied with powder and bullets . . . .” Though Douglass thought slavery was this force, Lincoln may have recognized the border states as a force which could do that same thing for the Union army: keep them fed, clothed, and supplied. To Douglass, though, the millstone was antithetical to the future of Black America and needed to be deconstructed: “strike here, the connection between fighting master and working slave.” The slave worked to create the wealth that (re)produced the system and the rebellion, thus abolition was a necessity to abolish the millstone. However much Douglass and Lincoln may have agreed on a moral level about slavery’s abolition, they fundamentally differed on the primacy of those different concerns at the start of the war.

Rallying his fellow abolitionists through Biblical allusions and opposition to moderate politics, Douglass critiqued these broader systems and created a path of hope forward if only the Union accepts the abolition of slavery as its foundational motive. Douglass made clear that the only way to rid the Black man’s neck of this stone, permanently keeping him suppressed and lowly, was to get rid of the institution which itself necessitated war and compromise. As Douglass would say, the United States must realize and actualize its foundational principles to extend the truest liberty to all citizens.

Citations

[1] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007), 54.

[2] Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, 151.

[3] Douglass, Frederick. “Cast off the Mill-stone,” Douglass’ Monthly (Rochester, New York), September, 1861.

[4] Amy Murrell Taylor, “The Border States,” National Parks Service, August 14, 2017, [WEB].

[5] Douglass, Frederick. “The Late Election,” Douglass’ Monthly (Rochester, New York), December, 1860.