Few Nineteenth Century newspaper editors, particularly in the decades before the Civil War, had the resources to hire lots of reporters to cover stories in their own cities or other states. While newspapers included editorials and reports written by their own staff in every issue, many also published content from other papers. As you read a newspaper from this period, it is important to watch out for these types of articles. Document records in House Divided include an “Original Source” field, which indicates whether that article was original published in another paper or contained an excerpt. Some papers, such as the Ripley (OH) Bee, might include the original publication above the article title.

Few Nineteenth Century newspaper editors, particularly in the decades before the Civil War, had the resources to hire lots of reporters to cover stories in their own cities or other states. While newspapers included editorials and reports written by their own staff in every issue, many also published content from other papers. As you read a newspaper from this period, it is important to watch out for these types of articles. Document records in House Divided include an “Original Source” field, which indicates whether that article was original published in another paper or contained an excerpt. Some papers, such as the Ripley (OH) Bee, might include the original publication above the article title.

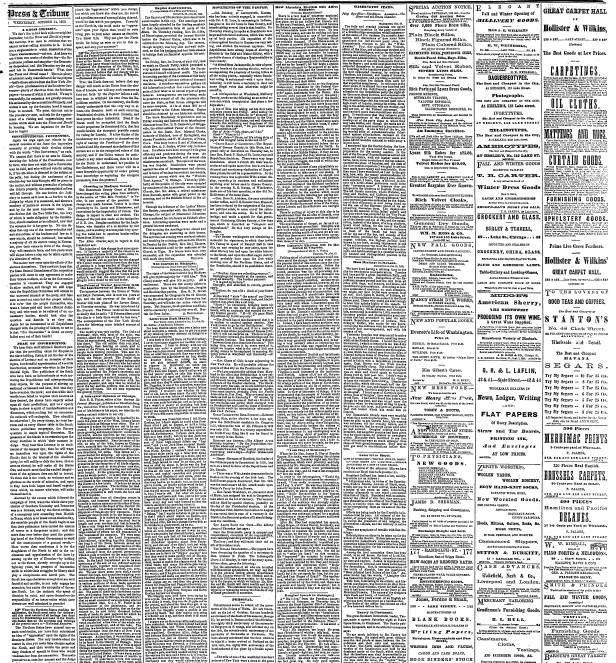

Other newspaper, such as the Chicago (IL) Press and Tribune, noted the original source directly below the article title. The Bangor (ME) Whig and Courier, however, usually gave credit to the other publications at the end of the article. As uniform standards did not exist, editors adopted their own guidelines for how or where to note the original source. In addition, some editorials might include extracts from articles published in other papers. These can be easier to quickly identify, as some papers indented the block quote or noted that part of the article had been “copied.” You can start to learn more about newspapers in this period from sources noted in a previous post.