Contributing Editors for this page include Brian Kellett and Jesse O’Neill

Ranking

#92 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“In a few days we had an interview, and although I had seen her before, she did not look as my immagination had pictured her. I knew she was over-size, but she now appeared a fair match for Falstaff; I knew she was called an “old maid”, and I felt no doubt of the truth of at least half of the appelation; but now, when I beheld her, I could not for my life avoid thinking of my mother…”

On This Date

HD Daily Report, April 1, 1838

The Lincoln Log, April 1, 1838

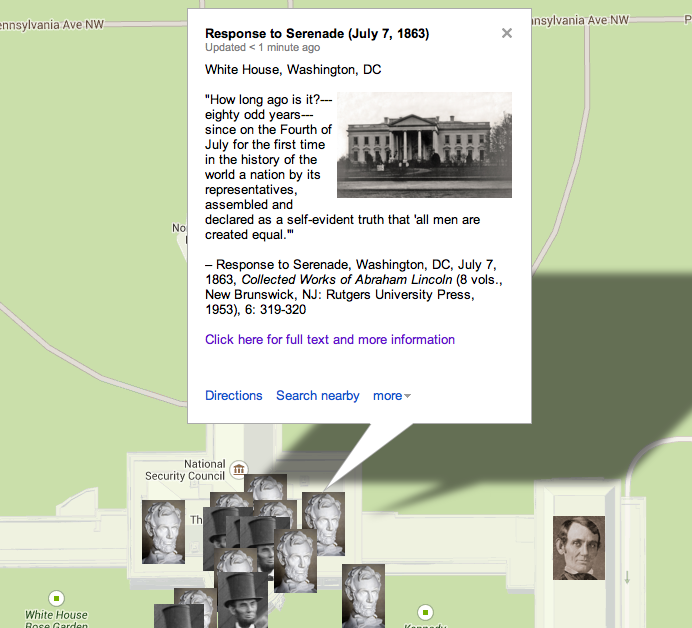

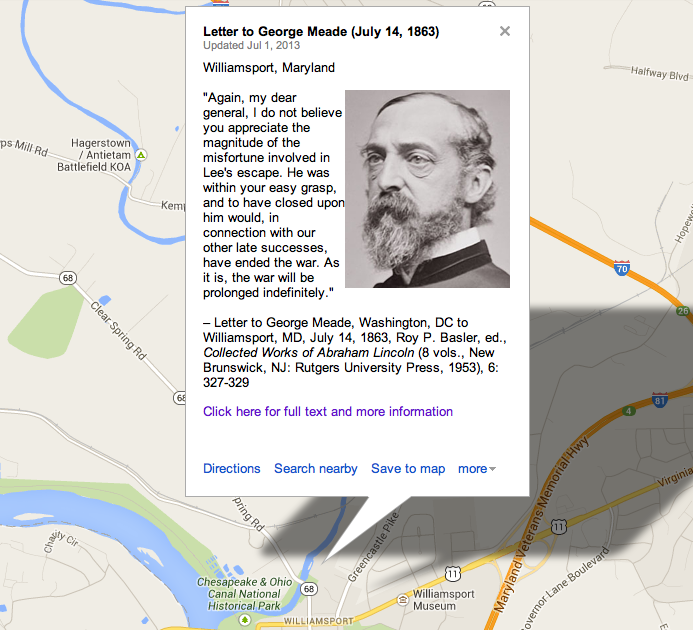

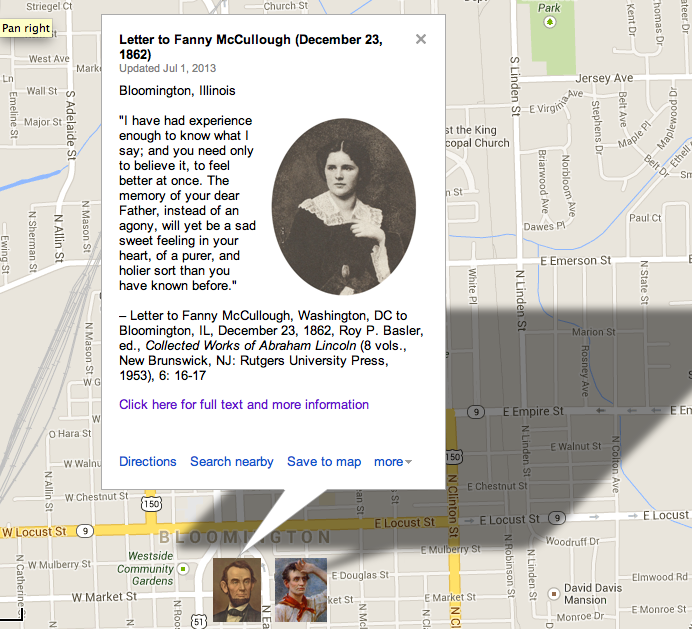

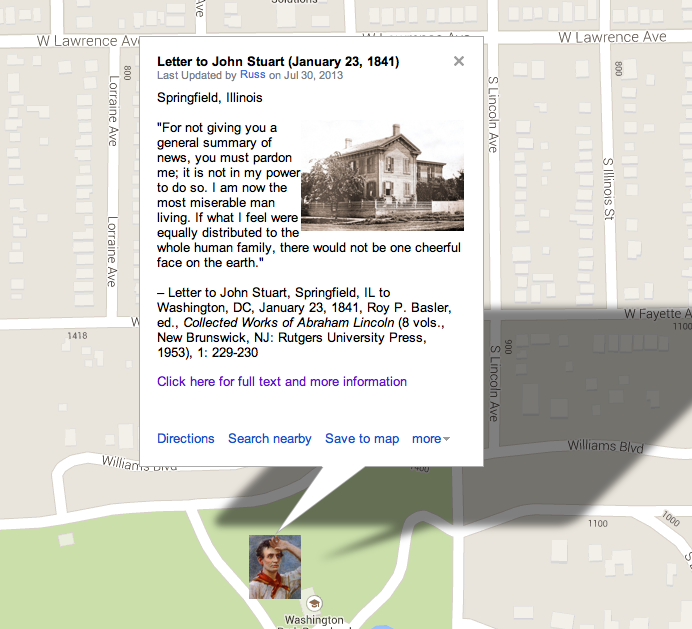

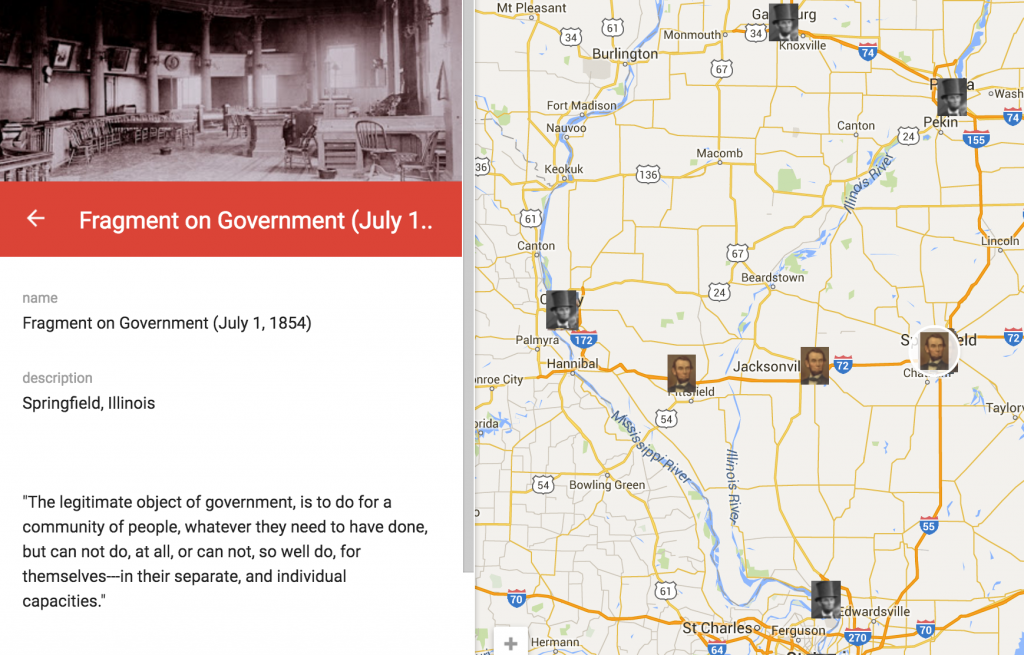

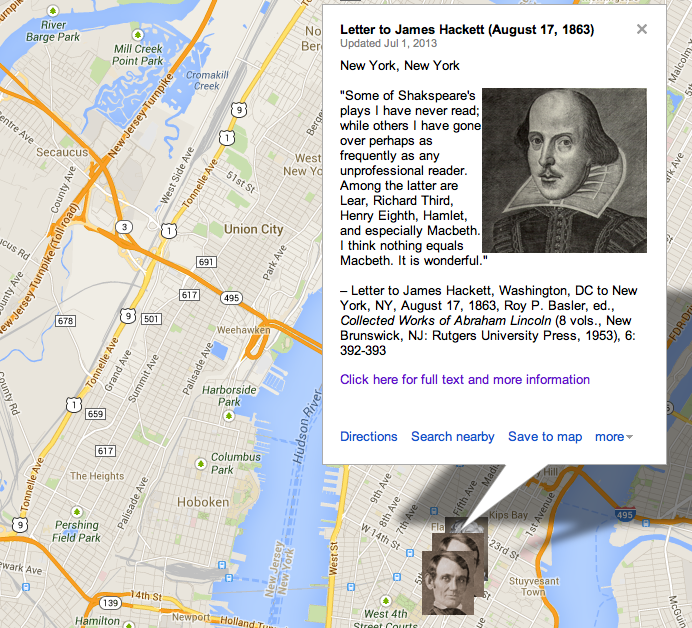

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

View in Larger Map

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” course participant Brian Kellett, August 2014

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” course participant Jesse O’Neill, July 2014

How Historians Interpret

“This account of the courtship is misleading, for Lincoln’s correspondence with Mary Owens indicates that he ‘had grown very fond’ of her and backed away only after she wounded him severely. A letter he wrote her in December 1836 from Vandalia “shows that Lincoln was in love – deeply in love.’ In it, Lincoln complained of ‘the mortification of looking in the Post Office for your letter and not finding it.’ He scolded her: ‘You see, I am mad about that old letter yet. I don’t like verry well to risk you again. I’ll try you once more anyhow.’ The prospect of spending ten weeks with the legislature in Vandalia was intolerable, he lamented, for he missed her. ‘Write back as soon as you get this, and if possible say something that will please me, for really I have not [been] pleased since I left you.’ Such language, hardly that of an indifferent suitor, tends to confirm Parthena Hill’s statement that ‘Lincoln thought a great deal” of Mary Owens.'”

Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume 1 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 520-521.

“There is at least one particular sense in which Lincoln could not have been ‘a very social man’ even if he had been inclined to it, and that concerned the most intimate community he belonged to, his marriage with Mary Todd Lincoln. Although the Lincoln marriage was suspected almost from the start for being ‘a policy Match all around,’ the fact is that all of Lincoln’s attempts at marriage were, in more than a few respects, policy matches. His sadly aborted love match with Ann Rutledge as well as his rebound proposal to Mary Owens were, whatever the quotient of affection in them, both potential marriages-up for Lincoln—Ann Rutledge, of course, belonged to the first family of New Salem (and while that may not have been very much of a social climb from Lincoln’s later perspective, it certainly was from New Salem’s) and Mary Owens was not only ‘jovial’ and ‘social’ but ‘had a liberal English education & was considered wealthy.'”

Allen C. Guelzo, “Come-outers and Community Men: Abraham Lincoln and the Idea of Community in Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 21, no. 1 (2000): 1-29.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

Springfield,

April 1. 1838.

Dear Madam:

Without appologising for being egotistical, I shall make the history of so much of my own life, as has elapsed since I saw you, the subject of this letter. And by the way I now discover, that, in order to give a full and inteligible account of the things I have done and suffered since I saw you, I shall necessarily have to relate some that happened before.

It was, then, in the autumn of 1836, that a married lady of my acquaintance, and who was a great friend of mine, being about to pay a visit to her father and other relatives residing in Kentucky, proposed to me, that on her return she would bring a sister of hers with her, upon condition that I would engage to become her brother-in-law with all convenient dispach. I, of course, accepted the proposal; for you know I could not have done otherwise, had I really been averse to it; but privately between you and me, I was most confoundedly well pleased with the project. I had seen the said sister some three years before, thought her inteligent and agreeable, and saw no good objection to plodding life through hand in hand with her. Time passed on, the lady took her journey and in due time returned, sister in company sure enough. This stomached me a little; for it appeared to me, that her coming so readily showed that she was a trifle too willing; but on reflection it occured to me, that she might have been prevailed on by her married sister to come, without any thing concerning me ever having been mentioned to her; and so I concluded that if no other objection presented itself, I would consent to wave this. All this occured upon my hearing of her arrival in the neighbourhood; for, be it remembered, I had not yet seen her, except about three years previous, as before mentioned.

In a few days we had an interview, and although I had seen her before, she did not look as my immagination had pictured her. I knew she was over-size, but she now appeared a fair match for Falstaff; I knew she was called an “old maid”, and I felt no doubt of the truth of at least half of the appelation; but now, when I beheld her, I could not for my life avoid thinking of my mother; and this, not from withered features, for her skin was too full of fat, to permit its contracting in to wrinkles; but from her want of teeth, weather-beaten appearance in general, and from a kind of notion that ran in my head, that nothing could have commenced at the size of infancy, and reached her present bulk in less than thirtyfive or forty years; and, in short, I was not all pleased with her. But what could I do? I had told her sister that I would take her for better or for worse; and I made a point of honor and conscience in all things, to stick to my word, especially if others had been induced to act on it, which in this case, I doubted not they had, for I was now fairly convinced, that no other man on earth would have her, and hence the conclusion that they were bent on holding me to my bargain. Well, thought I, I have said it, and, be consequences what they may, it shall not be my fault if I fail to do it. At once I determined to consider her my wife; and this done, all my powers of discovery were put to the rack, in search of perfections in her, which might be fairly set-off against her defects. I tried to immagine she was handsome, which, but for her unfortunate corpulency, was actually true. Exclusive of this, no woman that I have seen, has a finer face. I also tried to convince myself, that the mind was much more to be valued than the person; and in this, she was not inferior, as I could discover, to any with whom I had been acquainted.

Shortly after this, without attempting to come to any positive understanding with her, I set out for Vandalia, where and when you first saw me. During my stay there, I had letters from her, which did not change my opinion of either her intelect or intention; but on the contrary, confirmed it in both.

All this while, although I was fixed “firm as the surge repelling rock” in my resolution, I found I was continually repenting the rashness, which had led me to make it. Through life I have been in no bondage, either real or immaginary from the thraldom of which I so much desired to be free.

After my return home, I saw nothing to change my opinion of her in any particular. She was the same and so was I. I now spent my time between planing how I might get along through life after my contemplated change of circumstances should have taken place; and how I might procrastinate the evil day for a time, which I really dreaded as much—perhaps more, than an irishman does the halter.

After all my suffering upon this deeply interesting subject, here I am, wholly unexpectedly, completely out of the “scrape”; and I now want to know, if you can guess how I got out of it. Out clear in every sense of the term; no violation of word, honor or conscience. I dont believe you can guess, and so I may as well tell you at once. As the lawyers say, it was done in the manner following, towit. After I had delayed the matter as long as I thought I could in honor do, which by the way had brought me round into the last fall, I concluded I might as well bring it to a consumation without further delay; and so I mustered my resolution, and made the proposal to her direct; but, shocking to relate, she answered, No. At first I supposed she did it through an affectation of modesty, which I thought but ill-become her, under the peculiar circumstances of her case; but on my renewal of the charge, I found she repeled it with greater firmness than before. I tried it again and again, but with the same success, or rather with the same want of success. I finally was forced to give it up, at which I verry unexpectedly found myself mortified almost beyond endurance. I was mortified, it seemed to me, in a hundred different ways. My vanity was deeply wounded by the reflection, that I had so long been too stupid to discover her intentions, and at the same time never doubting that I understood them perfectly; and also, that she whom I had taught myself to believe no body else would have, had actually rejected me with all my fancied greatness; and to cap the whole, I then, for the first time, began to suspect that I was really a little in love with her. But let it all go. I’ll try and out live it. Others have been made fools of by the girls; but this can never be with truth said of me. I most emphatically, in this instance, made a fool of myself. I have now come to the conclusion never again to think of marrying; and for this reason; I can never be satisfied with any one who would be block-head enough to have me.

When you receive this, write me a long yarn about something to amuse me. Give my respects to Mr. Browning.

Your sincere friend

A. LINCOLN

Mrs. O. H. Browning.