Contributing Editors for this page include Susan Segal

Ranking

#87 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, July 14, 1863

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” participant, Susan Segal, October 18, 2013

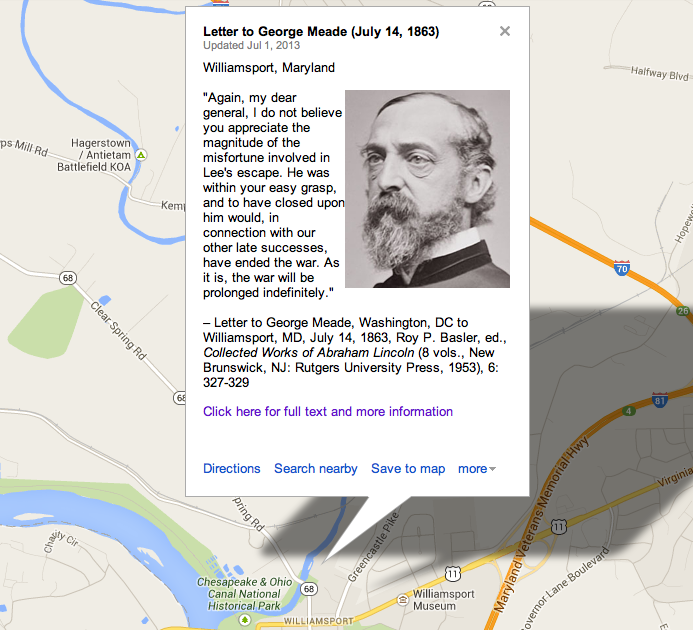

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“In one of the harshest passages Lincoln ever penned, he told Meade how much his failure to attack Lee would hurt the Union cause: “I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely. If you could not safely attack Lee last monday, how can you possibly do so South of the river, when you can take with you very few more than two thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect, and I do not expect you can now effect much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasureably because of it.” This stinging letter Lincoln filed away with the endorsement: “To Gen. Meade, never sent, or signed.” But he did tell the general, “The fruit seemed so ripe, so ready for plucking, that it was very hard to lose it.”

Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 30 (PDF), 3353.

“Lee’s escape made the president frantic, because he believed that Lee had been within Meade’s ‘easy grasp’ and to have ‘closed upon him would,’ he stated, ‘in connection with our late successes, have ended the war.’ With the Confederates’ back to the river, Lincoln’s expected that Lee’s army could have been destroyed and that ‘such destruction was perfectly easy.’ The president believed that victory was ‘certain’ and confided to his secretary: ‘We had them in our grasp. We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours.’”

Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 425.

“Like his committee counterparts, Lincoln did not take defeat or missed opportunity lightly. He, too, was convinced that George Meade had missed the opportunity of the war in allowing Lee’s escape after Gettysburg. His anger and grief were obvious to many who saw him in the aftermath of that battle. At a July [14], 1863, cabinet meeting, he complained bitterly to Gideon Welles, ‘there is bad faith somewhere. Meade has been pressed and urged, but only one of his generals was for an immediate attack…. What does it mean, Mr. Welles? Great God! What does it mean.’”

Bruce Tap, “Amateurs at War: Abraham Lincoln and the Committee on the Conduct of the War,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 23, no. 2 (2002): 1-18.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln