Ranking

#4 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

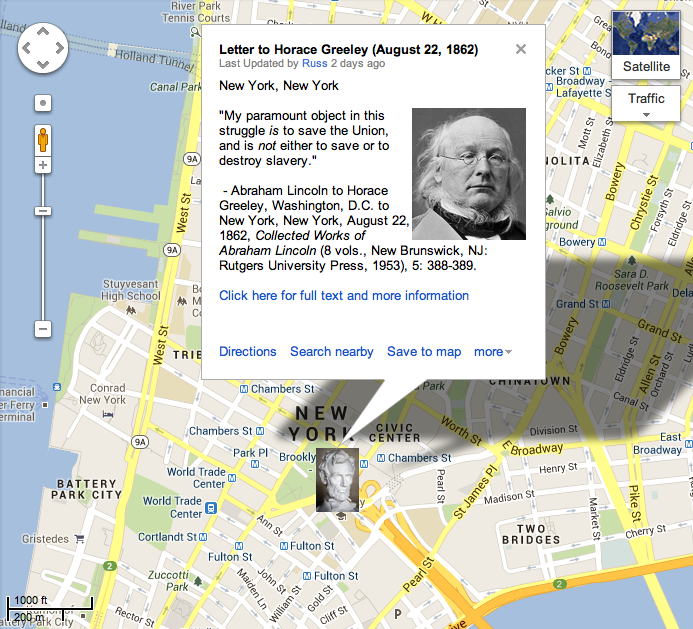

Context: Horace Greeley published an angry open “letter” to President Lincoln in the pages of his newspaper, the New York Tribune, on August 20, 1862. Greeley was upset that Lincoln had not yet begun enforcing the “emancipating provisions” of the new Second Confiscation Act (July 17, 1862). Lincoln responded in the pages of a rival newspaper with his own “letter” to Greeley that sternly laid out the president’s policy regarding slavery. Lincoln claimed his “paramount object” in the war was to “save the Union” and not “freeing all the slaves.” Yet by that point, Lincoln had already decided (in secret) that the only way he could “save the Union” was to issue an emancipation proclamation following the next major battlefield victory. (By Matthew Pinsker)

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, August 22, 1862

Image Gallery

- Lincoln in 1862

- Published Version

- Horace Greeley

- Original draft

- Edited draft

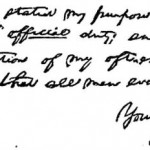

- Handwritten Closing

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Letter to Greeley (1862) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Horace Greeley letter to Abraham Lincoln, March 24, 1862

Horace Greeley, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” New York Tribune, August 20, 1862

Daily National Intelligencer, “The President at the Bar,” August 22, 1862

Thurlow Weed letter to Abraham Lincoln, August 24, 1862

James C. Wellling, former newspaper editor, recalls publishing Lincoln’s response to Greeley

How Historians Interpret

“Written at a time when the draft of the Emancipation Proclamation had already been completed, Lincoln’s letter to Greeley later seemed puzzling, if not deceptive. But the President did not intend it to be so. He was giving assurance to the large majority of the Northern people who did not want to see the war transformed into a crusade for abolition—and at the same time he was alerting antislavery men that he was contemplating further moves against the peculiar institution. In Lincoln’s mind there was no necessary disjunction between a war for the Union and a war to end slavery. Like most Republicans, he had long held the belief that if slavery could be contained it would inevitably die; a war that kept the slave states within the Union would, therefore, bring about the ultimate extinction of slavery. For this reason, saving the Union was his ‘paramount object.’ But readers aware that Lincoln always chose his words carefully should have recognized that ‘paramount’ meant ‘foremost’ or ‘principle’—not ‘sole.'”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 368-369

Further Reading

For educators:

- Handout –Greeley Letter (Pinsker)

- Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom, “Abraham Lincoln and Horace Greeley”

- Annenberg Learner, “What Did Lincoln Believe,” multi-unit lesson plan

For everyone:

- Civil War Trust, Greeley’s Letter and the Emancipation Proclamation (video)

- Gilder Lehrman Institute, timeline entry, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions”

- Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 147-52.

- Wilson, Douglas L. Chapter 6, “Public Opinion,” Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words. New York: Random House, 2006, pp. 143-61.

Searchable Text

Hon. Horace Greely: Executive Mansion,

Dear Sir Washington, August 22, 1862.

I have just read yours of the 19th. addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.

As to the policy I “seem to be pursuing” as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free. Yours,

A. LINCOLN