Ranking

#2 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

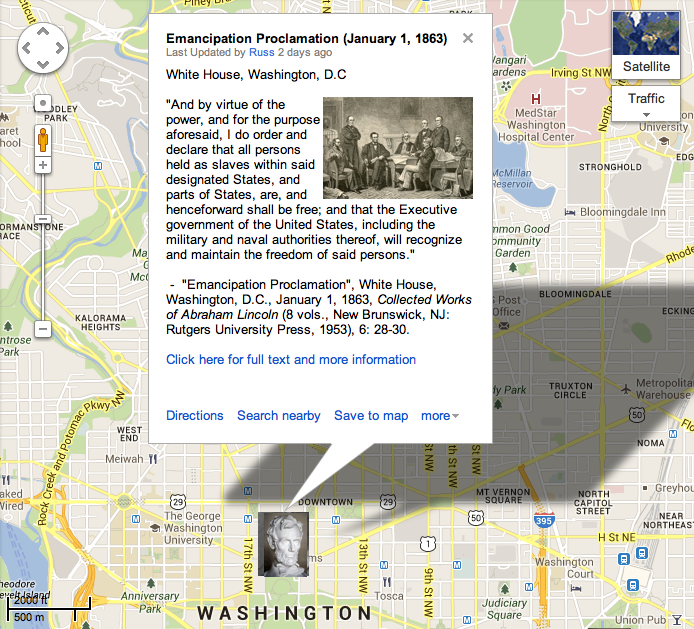

Context: The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 culminated more than eighteen months of heated policy debates in Washington over how to prevent Confederates from using slavery to support their rebellion. Lincoln drafted his first version of the proclamation in mid-July 1862, following passage of the landmark Second Confiscation Act, though he did not make his executive order public until September 22, 1862, after the Union victory at Antietam. The January 1st proclamation then promised to free enslaved people in Confederate states (with some specific exceptions for certain –but not all– areas under Union occupation) and authorized the immediate enlistment of black men in the Union military. The proclamation did not destroy slavery everywhere, but it marked a critical turning point in the effort to free slaves. (By Matthew Pinsker)

“Whereas on the twenty-second day of September….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, January 1, 1863

The Lincoln Log, January 1, 1863

Image Gallery

- Lincoln in 1863

- White House

- Image of Proclamation

- Emancipation in South Carolina

Close Readings

Transcript for video close reading

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Green Adams to Abraham Lincoln, December 31, 1862

Praise from the Bloede children, January 4, 1863 (Gertrude, age 17, Katie, age 16, and Victor, age 14)

New York Times, “The President’s Proclamation,” January 6, 1863

The Daily Southern Crisis (Jackson, Mississippi), “The Emancipation Proclamation,” January 24, 1863

New York City Republican Committee to Abraham Lincoln, January 28, 1863

Chicago Tribune, “The Emancipation Proclamation,” March 18, 1863

Abraham Lincoln to John M. Schofield, June 22, 1863

Leavenworth (Kansas) Evening Bulletin, “Emancipation,” September 2, 1863

How Historians Interpret

“But Lincoln was under increasing pressure to act. His call for additional volunteers had met a slow response, and several of the Northern governors bluntly declared that they could not meet their quotas unless the President moved against slavery. The approaching conference of Northern war governors would almost certainly demand an emancipation proclamation. He also had to take seriously the insistent reports that European powers were close to recognizing the Confederacy and would surely act unless the United States government took a stand against slavery.”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), pp. 374

“A striking new feature of the Proclamation was its hint that the administration would aid slave insurrections: ‘The executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize the freedom of such persons [freed slaves], and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.’ Lincoln doubtless meant that the Union army would not return runaways to bondage, though many would interpret his words to mean that the North would incite slave uprisings.

“. . . I believe that Abraham Lincoln understood from the first that his administration was the beginning of the end of slavery and that he would not leave office without some form of legislative emancipation policy in place. By his design, the burden would have to rest mainly on the state legislatures, largely because Lincoln mistrusted the federal judiciary and expected that any emancipation initiatives which came directly from his hand would be struck down in the courts . . . But why, if he was attuned so scrupulously to the use of the right legal means for emancipation, did Lincoln turn in the summer of 1862 and issue an Emancipation Proclamation—which was, for all practical purposes, the very sort of martial-law dictum he had twice before canceled? The answer can be summed up in one word: time. It seems clear to me that Lincoln recognized by July 1862 that he could not wait for the legislative option—and not because he had patiently waited to discern public opinion and four the North readier than the state legislatures to move ahead. If anything, Northern public opinion remained loudly and frantically hostile to the prospect of emancipation, much less emancipation by presidential decree. Instead of exhibiting patience, Lincoln felt stymied by the unanticipated stubbornness with which even Unionist slaveholders refused to cooperate with the mildest legislative emancipation policy he could devise, and threatened by generals who were politically committed to a negotiated peace . . . Thus Lincoln’s Proclamation was one of the biggest political gambles in American history.

Further Reading

- Prince of Emancipation (Google Arts & Culture)

Searchable Text