Completely unrelated, but in the spirit of the Olympics, here is a blog post about an Olympian buried at Maple Grove. I also find his sister fascinating as well. Imagine being a African American nurse during the Jim Crow era.

Completely unrelated, but in the spirit of the Olympics, here is a blog post about an Olympian buried at Maple Grove. I also find his sister fascinating as well. Imagine being a African American nurse during the Jim Crow era.

As a culmination field trip to our year and a half study of American history through the lens of New York City history, we travel to various parts of the city to ascertain the legacy of that history. One of the stops we make is Greenwood Cemetery, located in Brooklyn. We explore five monuments/grave sites and place our observations in the context of the arc of history we’ve studied. One of the sites we visit is the 1869 Civil War Soldiers’ Monument, erected in memory of the dead and the almost 150,000 enlisted servicemen on Battle Hill (where Washington faced the British in the Battle of Long Island at the start of the Revolutionary War).

As a culmination field trip to our year and a half study of American history through the lens of New York City history, we travel to various parts of the city to ascertain the legacy of that history. One of the stops we make is Greenwood Cemetery, located in Brooklyn. We explore five monuments/grave sites and place our observations in the context of the arc of history we’ve studied. One of the sites we visit is the 1869 Civil War Soldiers’ Monument, erected in memory of the dead and the almost 150,000 enlisted servicemen on Battle Hill (where Washington faced the British in the Battle of Long Island at the start of the Revolutionary War).

The monument is complex in construction and offers a wide variety of symbols (military and otherwise), figures, and apparently allegorical bas relief scenes.

http://www.green-wood.com/2010/civil-war-soldiers-monument-saved/

Reading Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter, of all places, I came upon excerpts from the second inaugural address that reminded me of the scenes depicted on the bas reliefs between full-sized sculptures representing the various branches of the Union Army.

According to the website from Green-Wood Cemetery (link above), these reliefs had text associated with them (but that text is currently missing). The monument was erected in Brooklyn in 1869, less than five years after the second inaugural address (Lincoln’s last great public speech on the conflict of the Civil War). Would these bas relief scenes be attempts at illustrating the final lines of that address?

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

-Abraham Lincoln, March 4, 1865

What do you think? And, is this a valid place to end the search for a national consciousness surrounding the Civil War conflict as a direct line from the public statements of John Brown?

Ready for the adventure to begin! I typed “Harriet Robinson Scott” into the rectangle marked “search” and nothing. Really, it said “zero”. How could that be? I know she’s in the G L database somewhere. Hmm, well, let’s try “women black history” and see what that yields. Okay, more like it. Lots of choices, but Harriet is not among the them. There are lots of goodies though. I’m like a small child wanting to grab the shiny images and click on the weblinks. Even though my mind is chanting history, history, I have to steady my hand away from the mouse. Regroup. Focus. I know Harriet is in here. But she’s not, even when I type in “Adam Arenson” the author of Freeing Dred Scott. The search still says “zero”. I am going to do like my students. Google. Sure enough. There is the article I saw Professor Pinsker discuss twice (I watched the video of the recap session.) Where is the “web guide” he put together for us? Oh, well, time to focus on Harriet. Here’s what I learned from the Arenson essay:

Harriet Robinson Scott (I like referring to people with their whole names–especially those enslaved!) was born in PA, was illiterate, she was Dred Scott’s second wife (interesting!!) she was proud of making a living separate from her husband (early feminist–I like her already) and when a reporter asked her to encourage her husband to go on a speaking tour after the trial, she replied, “Why don’t white man ‘tend his business, and let dat n—– ‘lone?”

She was quite the power house! But, there’s a mystery in Arenson’s article. He mentioned when Harriet died in Missouri on June 17, 1876, she was buried, next to her famous husband, in Greenwood Cemetery’s unmarked grave section.

Huh? Didn’t I have an image of her gorgeous tombstone in my last post? It seems in 1957, the 100th year anniversary of the Dred Scott, the granddaughter of Scott’s owner, donated the monies for a gravestone for Mr. Scott, but nothing was mentioned about Mrs.’s maker. Did the tombstone appear during the 150th anniversary in 2007? Google to the rescue again. Seems the grave yard was abandoned land by 1994, but a group of historically minded folks pitched in time and money to revitalize it. “Harriet’s Hill” complete with the tombstone and pavillion was dedicated in 2010.

Funny how the scavener hunt to find Harriet yielded the most information on her grave, but doggone it, not her. Still looking for Harriet.

Growing up in Jamaica, I learned virtually nothing of American history as a student. In high school, my classmates and I were taught the history of the Caribbean within a British context. To say I was not interested in history would be an understatement. In my mind, I could not see the value or how it related to me. The fact that I was convinced that my history teacher hated me also turned me off from the subject. She would probably fall out of a chair now if she knew I was a history teacher! In college I took art history as a humanities requirement, and my teacher was fascinating. However, once that course was complete I figured that my engagement with history was too.

Last year, my second as a high school teacher, was the first time I taught American history. Prior to teaching, I practiced law for almost 10 years and people have assumed that I was taught history in law school. Not quite; I learned case law, but not necessarily the complex history in which decisions were handed down. I had never even taken a course in American history. Today Professor Pinsker taught us about the concept of coverture as it related to Harriet Scott’s role in her family’s legal case. It was my first time even hearing the word. (Apologies to my law school property professor if I was sleeping had not paid attention during that particular lesson!) Though not by choice (thank you Principal Chang!), as I waded through unfamiliar academic territory, my love affair with history was ignited. So much, that I am currently working on a Master’s degree in the discipline and now consider myself a historian-in-training. It is never too late to look with new eyes, and an open mind.

Technology is a huge passion of mine and I am very excited to share the Gilder Lehrman Resources not only my students, but with my classmates who are also educators. Textbooks often leave the readers feeling that time periods come in neat little packages, with the people in history waiting on standby for the next era to begin. Professor Pinkser offered complex perspectives of Dred Scott, John Brown, and the time period before the Civil War, which left my mind reeling with the possibilities for new approaches to teaching the material. He mentioned a quote (Can I hear that one again please Professor Pinsker?) by Ralph Waldo Emerson on the Dred Scott decision, which sparked my interest in Emerson’s role in the Civil War. The House Divided resources are excellent, especially for discussing quality academic research. With students who are digital natives, new methods must be incorporated into making history come alive and the interactive nature of these primary resources provides just that.

This past school year I viewed American history through a lens that was not much different from that of my students, and was challenged with making the subject one with which they (read: we) could relate. I remembered exactly how it felt to be sitting in my high school class thinking, why do I even need to know this? Most of my students were either immigrants or descended from immigrants, and did not believe that American history related to their lives. They did not know the history of their home countries, moreover how any of it related to America. As the first person in my family born in the United States, I could understand how they felt and this perspective helped me to connect our histories.

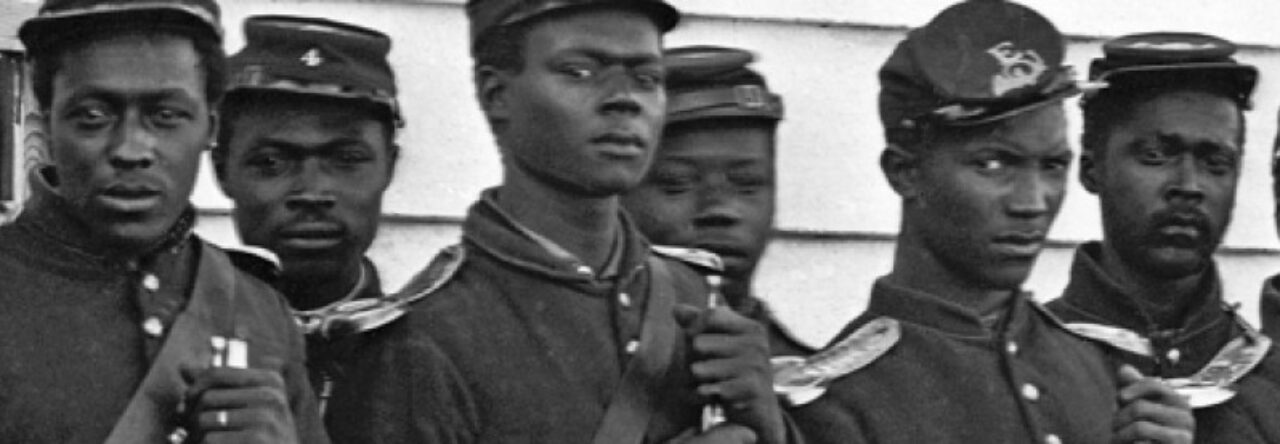

Members of Company E, Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, at Fort Lincoln, Maryland. During the Civil War the regiment lost nearly 300 men. (Library of Congress)

In Why Do So Few Blacks Study The Civil War, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote of how black Americans see no greatness in themselves, and “thus no future glory”. On a field trip to Gettysburg he felt no connection to the history of the Civil War. Coates’ understanding as a middle-school student at the time, was that the legacy of the Civil War belonged “not to us, but to those who reveled in the costume and technology of a time when we were property”. If this was the case for American students, imagine how it must be for students of different countries and cultures. My district required that I teach from three different history texts, yet in none of them would my students ever read about the role of black people during the Civil War besides Americans. This is one reason why primary source analysis played a crucial role in my classroom; textbooks alone are never enough.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, radical American abolitionist missionaries drew from their experiences in Jamaica.

My students and I are mostly from the Caribbean, so in order to make the connections for us I pored over the available research. We learned that the Union blockade created an economic hardship for the people of Jamaica, and of the role our Jamaican and Haitian ancestors played in the Civil War. In the Journal of the Civil War Era, Matthew J. Calvin in his analysis of Gale L. Kenny’s Book Contentious Liberties: American Abolitionists in Post-Emancipation Jamaica 1834-1866 stated, “Historians are only now beginning to recognize what American abolitionists long understood, that the end of slavery outside the United States had an important effect on the movement to secure its end inside the United States.” In the Civil War History Journal in an article titled A Second Haitian Revolution: John Brown, Toussaint Louverture, and the Making of the American Civil War, Calvin discussed how the events leading to revolution in Haiti “had a profound impact on the American mind”. These are some examples of why I am so excited to learn and share with my students about the Civil War, and how much our history as Caribbean blacks is woven into the fabric of the United States.

When Professor Pinsker (I mean Matt) spoke of how Abraham Lincoln used quotes from John Brown’s trial in his second inaugural address it sent shivers down my spine. The two of them were closer idyllically than either wanted to admit.

It was September 20,2009 I was standing on a floor in the Adair cabin. My feet were still upon the floor where 150 years ago escaped slaves had seeked refuge for a night. It was also a place John Brown frequented to be safe. It was the house of his cousins the Adairs. I was part of the Freedom Festival for the John Brown Museum in Osawatomie ,Kansas . I stood their in my Lincoln attire feeling proud of who I was about to portray on stage. Yet an uneasy feeling came over me as if someone wanted me to never enter the cabin . I felt some eyes pearcing into me. I slowly turned and saw a women in civil war period dress in Florella Adair’s rocking chair . Her eyes were watery and seemed full of hate. I gracefully and as peacefully as possible extended my hand “I’m Abraham Lincoln” “I’m Florella Adair and you have unjustly and cruely ruined the good deeds of John Brown”. We stayed in character for twenty minutes and through many tears and a patient ear we agreed both men wanted the same thing.Somehow I had won her over . She hugged me and I hugged her . In my speech I stayed true to Lincoln’s words but I did not condem John Brown’s character. The woman I talked to, her real name was Mary Buster, Florella Adair’s great-great-grandaughter.

The idea which I’ve been wrestling with today is state’s rights. Here’s how the state’s rights argument has played out for me in the past.

The statement goes something like this. The Civil War wasn’t about slavery. No right thinking person could then or can now defend the institution. It was a moral wrong in 1619 when Dutch traders bartered slaves for ship repairs. It was a moral wrong during our founding and the founders knew it. It was wrong in 1861.

But then the statement takes a left turn:

The war was really fought over the rights of the states. A states right to secede. A states right to manage its economy as it saw fit. The right to an ethos and lifestyle unique to its people and culture; the noble Lost Cause.

When my student’s raise state’s rights, I send them to see Mr. Alexander Stephens of Georgia. Stephens served in the House of Representatives with Mr. Lincoln. He became the Vice-President of the Confederacy when Georgia secedes and will deliver what has become known as the Cornerstone Speech, a portion of which is excerpted here:

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

Alexander Stephens, March 21, 1861

Stephen’s thesis is that the Confederacy’s Constitution is stronger than the Union’s because slavery is the manifestation of a ‘physical, philosophical and moral truth’ on which the federal document is silent.

It makes a pretty persuasive argument for the cause of the war: The second in command of the South says its about slavery. The challenge for me, is that today’s lecture muddies the water a bit.

The concept of states rights predates the Civil War, but I don’t know if I’ve ever really given it its due. In class, we breeze through the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions and Calhoun taking up the Jefferson/Madison mantle. We look at Dred Scott as a case about slaves as citizens without looking at Chief Justice Taney’s argument about federal supremacy in this case and Abelman v. Booth.

The argument I’m wrestling with is this: if Wisconsin can cry states rights in 1859, why can’t South Carolina in 1860? Dr. Pinsker’s suggestion is that states rights is a mean’s to an end–the end being slavery. But I’m struggling with how cut and dry that feels.

Reflecting is beneficial for me. It helps when uncovering layers of historical documentation. Except the amount of sources and resources in the Gilder Lehrman collection might set a record for weblinked interactive media! So, my blogging posts will be a Civil War journey of commenting on what I already know, exclaiming about discovered items/concepts and designating new information spaces within my pre-existing history courses. As an African Americanist  with a tendency towards Women’s history, I am intrigued by Harriet Robinson Scott. She’s that behind every good man there’s a woman figure. And yet, she does not possess a historical voice. Or did she? I plan on tying her story into other female narratives, women who history may not have recognized as powerful per se, but who made the proactive difference.

with a tendency towards Women’s history, I am intrigued by Harriet Robinson Scott. She’s that behind every good man there’s a woman figure. And yet, she does not possess a historical voice. Or did she? I plan on tying her story into other female narratives, women who history may not have recognized as powerful per se, but who made the proactive difference.

I’ll be back to post. Not too far away, just far enough to ponder….

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén