Me on the left with two of my best high school friends, circa 1992

Growing up in Jamaica, I learned virtually nothing of American history as a student. In high school, my classmates and I were taught the history of the Caribbean within a British context. To say I was not interested in history would be an understatement. In my mind, I could not see the value or how it related to me. The fact that I was convinced that my history teacher hated me also turned me off from the subject. She would probably fall out of a chair now if she knew I was a history teacher! In college I took art history as a humanities requirement, and my teacher was fascinating. However, once that course was complete I figured that my engagement with history was too.

Harriet Scott, wife of Dred Scott

Last year, my second as a high school teacher, was the first time I taught American history. Prior to teaching, I practiced law for almost 10 years and people have assumed that I was taught history in law school. Not quite; I learned case law, but not necessarily the complex history in which decisions were handed down. I had never even taken a course in American history. Today Professor Pinsker taught us about the concept of coverture as it related to Harriet Scott’s role in her family’s legal case. It was my first time even hearing the word. (Apologies to my law school property professor if I was sleeping had not paid attention during that particular lesson!) Though not by choice (thank you Principal Chang!), as I waded through unfamiliar academic territory, my love affair with history was ignited. So much, that I am currently working on a Master’s degree in the discipline and now consider myself a historian-in-training. It is never too late to look with new eyes, and an open mind.

Bus Ride to Zora Neale Hurston's Gravesite, July 2012

Technology is a huge passion of mine and I am very excited to share the Gilder Lehrman Resources not only my students, but with my classmates who are also educators. Textbooks often leave the readers feeling that time periods come in neat little packages, with the people in history waiting on standby for the next era to begin. Professor Pinkser offered complex perspectives of Dred Scott, John Brown, and the time period before the Civil War, which left my mind reeling with the possibilities for new approaches to teaching the material. He mentioned a quote (Can I hear that one again please Professor Pinsker?) by Ralph Waldo Emerson on the Dred Scott decision, which sparked my interest in Emerson’s role in the Civil War. The House Divided resources are excellent, especially for discussing quality academic research. With students who are digital natives, new methods must be incorporated into making history come alive and the interactive nature of these primary resources provides just that.

11th Grade History Class Field Trip, April 2012

This past school year I viewed American history through a lens that was not much different from that of my students, and was challenged with making the subject one with which they (read: we) could relate. I remembered exactly how it felt to be sitting in my high school class thinking, why do I even need to know this? Most of my students were either immigrants or descended from immigrants, and did not believe that American history related to their lives. They did not know the history of their home countries, moreover how any of it related to America. As the first person in my family born in the United States, I could understand how they felt and this perspective helped me to connect our histories.

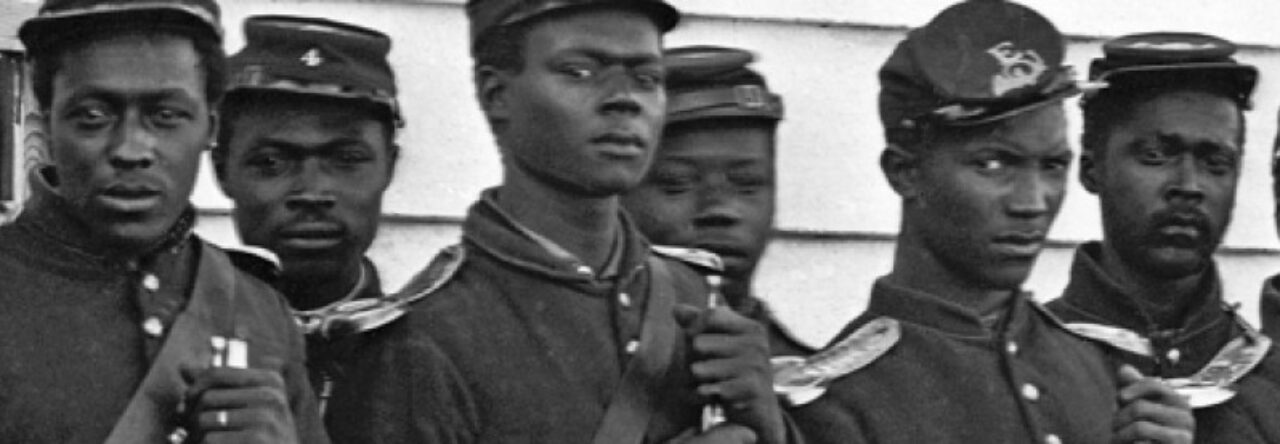

Members of Company E, Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, at Fort Lincoln, Maryland. During the Civil War the regiment lost nearly 300 men. (Library of Congress)

In Why Do So Few Blacks Study The Civil War, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote of how black Americans see no greatness in themselves, and “thus no future glory”. On a field trip to Gettysburg he felt no connection to the history of the Civil War. Coates’ understanding as a middle-school student at the time, was that the legacy of the Civil War belonged “not to us, but to those who reveled in the costume and technology of a time when we were property”. If this was the case for American students, imagine how it must be for students of different countries and cultures. My district required that I teach from three different history texts, yet in none of them would my students ever read about the role of black people during the Civil War besides Americans. This is one reason why primary source analysis played a crucial role in my classroom; textbooks alone are never enough.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, radical American abolitionist missionaries drew from their experiences in Jamaica.

My students and I are mostly from the Caribbean, so in order to make the connections for us I pored over the available research. We learned that the Union blockade created an economic hardship for the people of Jamaica, and of the role our Jamaican and Haitian ancestors played in the Civil War. In the Journal of the Civil War Era, Matthew J. Calvin in his analysis of Gale L. Kenny’s Book Contentious Liberties: American Abolitionists in Post-Emancipation Jamaica 1834-1866 stated, “Historians are only now beginning to recognize what American abolitionists long understood, that the end of slavery outside the United States had an important effect on the movement to secure its end inside the United States.” In the Civil War History Journal in an article titled A Second Haitian Revolution: John Brown, Toussaint Louverture, and the Making of the American Civil War, Calvin discussed how the events leading to revolution in Haiti “had a profound impact on the American mind”. These are some examples of why I am so excited to learn and share with my students about the Civil War, and how much our history as Caribbean blacks is woven into the fabric of the United States.

lived in Denton on the Eastern Shore of Maryland for two years. l did not know until today that it was possibly through this town that Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom or that Frederick Douglass was born in nearby Tuckahoe and worked on the Wye Plantation in Easton. I learned this in my research when I visited Maryland Public Television’s website.

lived in Denton on the Eastern Shore of Maryland for two years. l did not know until today that it was possibly through this town that Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom or that Frederick Douglass was born in nearby Tuckahoe and worked on the Wye Plantation in Easton. I learned this in my research when I visited Maryland Public Television’s website.