“The war was a good time for the study of the conflict between Athens and Sparta,” Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) wrote in 1897. “It was a great time for reading and re-reading classical literature in general, for the South was blockaded against new books as effectively, almost, as Megara was blockaded against garlic and salt… The Southerner, always conservative in his tastes and no great admirer of American literature, which had become largely alien to him, went back to his English classics, his ancient classics. Old gentlemen past the military age furbished up their Latin and Greek. Some of them had never let their Latin and Greek grow rusty.”

“The war was a good time for the study of the conflict between Athens and Sparta,” Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) wrote in 1897. “It was a great time for reading and re-reading classical literature in general, for the South was blockaded against new books as effectively, almost, as Megara was blockaded against garlic and salt… The Southerner, always conservative in his tastes and no great admirer of American literature, which had become largely alien to him, went back to his English classics, his ancient classics. Old gentlemen past the military age furbished up their Latin and Greek. Some of them had never let their Latin and Greek grow rusty.”

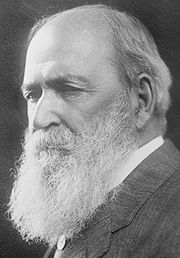

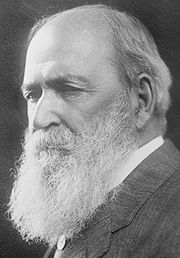

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and received his first schooling from his father, who was a Presbyterian clergyman and newspaper editor. Young Gildersleeve was reading ancient Greek fluently at the age of twelve, and at nineteen had graduated from Princeton (class of 1849) and had set off for Göttingen, Germany, where he earned a doctorate in classical philology in 1853. He was a professor of Greek at the University of Virginia from 1856 until 1876, when he left to become the first professor of Greek at the new Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

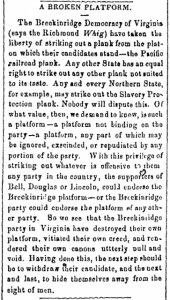

From 1861 to 1864, Gildersleeve served as a staff officer with General John B. Gordon. A staunch supporter of the Confederacy, he also contributed regular wartime editorials to the Richmond Examiner, edited by John Moncure Daniel, which have been collected by Ward W. Briggs, Jr. in Soldier and Scholar: Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve and the Civil War (University Press of Virginia 1998). Gildersleeve’s service with the Confederate army ended in September 1864, during the Valley Campaigns, when a bullet shattered his leg.

“I lost my pocket Homer, I lost my pistol, I lost one of my horses and, finally, I came very near losing my life,” he later wrote. General Gordon, in his memoirs, praised Gildersleeve’s “courage and composure” under fire, and Gildersleeve claimed that the general’s praise meant more to him than any of the academic honors he had received.

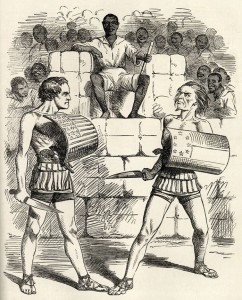

At Johns Hopkins after the war, Gildersleeve founded the prestigious American Journal of Philology, wrote a Latin grammar that would become a standard for generations to come, and reflected on the Civil War in essays like “The Creed of the Old South,” which promoted the idea of the Lost Cause. (Writing about Demosthenes in the American Journal of Philology in 1906, Gildersleeve called the Greek orator “a champion of a lost cause,” and added, “some of us who have championed lost causes are not so enthusiastic about other people’s lost causes.”) In “A Southerner in the Peloponnesian War,” quoted above, Gildersleeve reflects on the American Civil War in light of the Peloponnesian War, the conflict in the fifth century BCE between the northern Greek Athenians and the southern Greek Spartans.

“States rights were not suffered to slumber,” he wrote in that essay. “The Southerner resented Northern dictation as Pericles resented Lacedaimonian [i.e., Spartan] dictation, and our Peloponnesian War began.”

For more on Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve online, see James Stimpert, “Hopkins History: First Greek Prof., Basil Gildersleeve,” The Johns Hopkins Gazette, September 18, 2000; and Michael Dirda, “To Understand Ourselves,” Johns Hopkins Magazine, August 27, 2009. Both “The Creed of the Old South” and “A Southerner in the Peloponnesian War” can be read on Google Books.

This weekend, Northfield, Minnesota, has been host to the

This weekend, Northfield, Minnesota, has been host to the  “The war was a good time for the study of the conflict between Athens and Sparta,” Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) wrote in 1897. “It was a great time for reading and re-reading classical literature in general, for the South was blockaded against new books as effectively, almost, as Megara was blockaded against garlic and salt… The Southerner, always conservative in his tastes and no great admirer of American literature, which had become largely alien to him, went back to his English classics, his ancient classics. Old gentlemen past the military age furbished up their Latin and Greek. Some of them had never let their Latin and Greek grow rusty.”

“The war was a good time for the study of the conflict between Athens and Sparta,” Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) wrote in 1897. “It was a great time for reading and re-reading classical literature in general, for the South was blockaded against new books as effectively, almost, as Megara was blockaded against garlic and salt… The Southerner, always conservative in his tastes and no great admirer of American literature, which had become largely alien to him, went back to his English classics, his ancient classics. Old gentlemen past the military age furbished up their Latin and Greek. Some of them had never let their Latin and Greek grow rusty.”