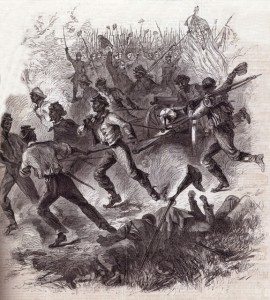

On August 10, 1861 about ten miles south of Springfield, Missouri Confederate forces under the joint command of General Benjamin McCulloch and Major General Sterling Price of the Missouri State Guard, defeated General Nathaniel Lyon’s Union troops at the battle of Wilson’s Creek. The National Park Service provides information geared towards teachers on their website, which highlights the field trip-friendly nature of the Wilson’s Creek battlefield. According to historian James McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom, although the Confederate victory at Wilson’s Creek did not affect national public opinion, the battle had a direct impact on communities within Missouri. The Missouri State Senate officially declared Missouri’s secession from the Union on October 28, 1861, only three months after the battle at Wilson’s Creek. The Journal of the Missouri Senate’s Extra Session of the Rebel Legislature has been digitized as part of the Missouri Digital Heritage Initiative and is available here. Another rich online source for teachers exploring the Western theater of the Civil War is the website “Community and Conflict,” which documents the impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks from 1850 to 1875. By searching the Wilson’s Creek Collections researchers can access the journal of Captain Asbury C. Bradford of Company E, 2nd Regiment, 8th Division, Missouri State Guard, which includes Asbury’s hand-drawn map of the battle at Wilson’s Creek. Another unique resource is the memoir of Louisa Cheairs McKenny Sheppard, a 12-year-old resident of Springfield, who documented the effects of the Civil War on her family. The night before General Lyon was killed at Wilson’s Creek he dined at the McKenny home, an event that Louisa recorded in her memoir:

On August 10, 1861 about ten miles south of Springfield, Missouri Confederate forces under the joint command of General Benjamin McCulloch and Major General Sterling Price of the Missouri State Guard, defeated General Nathaniel Lyon’s Union troops at the battle of Wilson’s Creek. The National Park Service provides information geared towards teachers on their website, which highlights the field trip-friendly nature of the Wilson’s Creek battlefield. According to historian James McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom, although the Confederate victory at Wilson’s Creek did not affect national public opinion, the battle had a direct impact on communities within Missouri. The Missouri State Senate officially declared Missouri’s secession from the Union on October 28, 1861, only three months after the battle at Wilson’s Creek. The Journal of the Missouri Senate’s Extra Session of the Rebel Legislature has been digitized as part of the Missouri Digital Heritage Initiative and is available here. Another rich online source for teachers exploring the Western theater of the Civil War is the website “Community and Conflict,” which documents the impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks from 1850 to 1875. By searching the Wilson’s Creek Collections researchers can access the journal of Captain Asbury C. Bradford of Company E, 2nd Regiment, 8th Division, Missouri State Guard, which includes Asbury’s hand-drawn map of the battle at Wilson’s Creek. Another unique resource is the memoir of Louisa Cheairs McKenny Sheppard, a 12-year-old resident of Springfield, who documented the effects of the Civil War on her family. The night before General Lyon was killed at Wilson’s Creek he dined at the McKenny home, an event that Louisa recorded in her memoir:

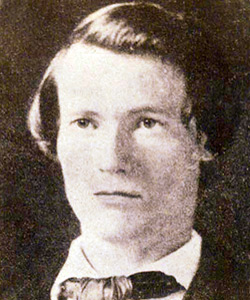

- “During dinner he [Lyon] raised his wine glass to Mother, and said, ‘Madam, you wish us success?’ ‘Sir,’ she answered with grave dignity, ‘I am a Southern woman.’ He looked at her in utter amazement, then said, ‘And you have sons in the Confederacy?’ Mother’s fine grey eyes were dark with trouble, as she made answer; ‘Four,’ then with a sudden flash of spirit, ‘and I wish they were fifty and I were leading them.’”

On August 10, 1861 about ten miles south of Springfield, Missouri Confederate forces under the joint command of General Benjamin McCulloch and Major General Sterling Price of the Missouri State Guard, defeated General Nathaniel Lyon’s Union troops at the battle of Wilson’s Creek. The National Park Service provides information geared towards teachers on their website, which highlights the field trip-friendly nature of the Wilson’s Creek battlefield. According to historian James McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom, although the Confederate victory at Wilson’s Creek did not affect national public opinion, the battle had a direct impact on communities within Missouri. The Missouri State Senate officially declared Missouri’s secession from the Union on October 28, 1961, only three months after the battle at Wilson’s Creek. The Journal of the Missouri Senate’s Extra Session of the Rebel Legislature has been digitized as part of the Missouri Digital Heritage Initiative and is available here. Another rich online source for teachers exploring the Western theater of the Civil War is the website “Community and Conflict,” which documents the impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks from 1850 to 1875. By searching the Wilson’s Creek Collections researchers can access the journal of Captain Asbury C. Bradford of Company E, 2nd Regiment, 8th Division, Missouri State Guard, which includes Asbury’s hand-drawn map of the battle at Wilson’s Creek. Another unique resource is the memoir of Louisa Cheairs McKenny Sheppard, a 12-year-old resident of Springfield, who documented the effects of the Civil War on her family. The night before General Lyon was killed at Wilson’s Creek he dined at the McKenny home, an event that Louisa recorded in her memoir:

“During dinner he [Lyon] raised his wine glass to Mother, and said, ‘Madam, you wish us success?’ ‘Sir,’ she answered with grave dignity, ‘I am a Southern woman.’ He looked at her in utter amazement, then said, ‘And you have sons in the Confederacy?’ Mother’s fine grey eyes were dark with trouble, as she made answer; ‘Four,’ then with a sudden flash of spirit, ‘and I wish they were fifty and I were leading them.’”

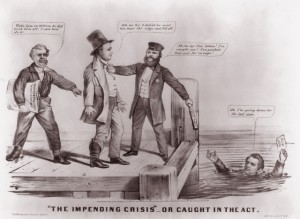

The Republican Party held its second national convention beginning at noon on May 16, 1860 in Chicago. The presidential nominees included the veteran statesmen Edward Bates, Salmon P. Chase, Simon Cameron, and William H. Seward, as well as a new senator from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln. Although Seward was the favorite going into the convention and led the nominees on the first two ballots, Lincoln won the Republican presidential candidacy. Republican delegates had looked to back the candidate they felt could generate the most electoral support. Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, had the ears of 48 delegates. Greeley’s battle cry was “anyone but Seward!” and initially gave his support to Bates. According to Greeley’s recent biographer Robert Chadwell Williams, as Lincoln began closing in on Seward in the third ballot, Greeley shifted his 48 votes over to Lincoln, giving him the candidacy.

The Republican Party held its second national convention beginning at noon on May 16, 1860 in Chicago. The presidential nominees included the veteran statesmen Edward Bates, Salmon P. Chase, Simon Cameron, and William H. Seward, as well as a new senator from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln. Although Seward was the favorite going into the convention and led the nominees on the first two ballots, Lincoln won the Republican presidential candidacy. Republican delegates had looked to back the candidate they felt could generate the most electoral support. Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, had the ears of 48 delegates. Greeley’s battle cry was “anyone but Seward!” and initially gave his support to Bates. According to Greeley’s recent biographer Robert Chadwell Williams, as Lincoln began closing in on Seward in the third ballot, Greeley shifted his 48 votes over to Lincoln, giving him the candidacy.

On August 10, 1861 about ten miles south of Springfield, Missouri Confederate forces under the joint command of

On August 10, 1861 about ten miles south of Springfield, Missouri Confederate forces under the joint command of