Gooden headstone (Courtesy of Cooper Wingert)

For the first twenty years of its existence, there were no black veterans buried in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg. That famous military cemetery, where President Lincoln had spoken so eloquently about a “new birth of freedom,” was not integrated until 1884, with the burial of Henry Gooden, an African American Civil War soldier from York, PA who had originally enlisted in Carlisle. Over the next few decades, the U.S. army interred at least five other black veterans in the cemetery’s Civil War section. The question is why? Were they buried there intentionally, to help integrate the “hallowed ground”?

Congress authorized the enlistment of black men in the Union army with the Militia Act of July 17, 1862, though President Lincoln did not lend his public support to this policy until the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Yet by the time of the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, only some black regiments had been mobilized (as United States Colored Troops), and none of them were yet incorporated into the Army of the Potomac.[1] In addition, during the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania in June 1863, Union general Darius Couch, the departmental commander in charge of the state’s defense, actually turned away a group of black volunteers from Philadelphia.[2] For these reasons, no African Americans fought officially at Gettysburg for either the Union field army or the local militias and thus there were no black soldiers to bury afterwards at the national cemetery when President Lincoln was present to help dedicate it on November 19, 1863

Gooden’s enlistment card (Courtesy of Fold3)

In 1884, however, Henry Gooden, a black veteran who had died in 1876, was reinterred at the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg. Private Henry Gooden does not seem to appear in census records, but his enlistment papers indicate that he was born in York, Pennsylvania in 1821, worked as a laborer, and stood 5’3″. Gooden enlisted in Carlisle in August 1864 for one year, where he was signed into the Union army by Provost Marshal Robert M. Henderson, a graduate of Dickinson College. Gooden, who was literate, served in Company C of the 127th United States Colored Troops. [3] The 127th USCT saw combat briefly near the end of the war and was present for General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. [4] Gooden survived the war, and actually mustered out of service from Texas in late 1865. He seems to have returned to Carlisle, however, where he died in August 1876. [5] However, on November 8, 1884, Gooden was reburied in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg in the U.S. Regulars Plot, section D, site 30. [6] Local historian Deb McCauslin claims that the family of the white soldier buried next to Gooden then had his body removed in protest, though park historians have remained somewhat skeptical of that connection, arguing there is no documentary evidence detailing the motivation for the re-interment. [7]

Henry Gooden’s official enlistment papers, signed by Dickinsonian Robert Henderson (Courtesy of Fold3)

Harry S. Prager Headstone. Courtesy of Karl Stelly and Find a Grave.

In 2012, Gettysburg military park historian D. Scott Hartwig wrote a fascinating blog post about the discovery of a photographic image in the NPS archives depicting black army regulars burying one of their own at Gettysburg in 1898. Hartwig identifies a total of four black soldiers who died from disease during the Spanish American War and were buried at Gettysburg in late 1898. These men were Clifford Henderson, Emmert Martin, and Nicholas Farrell, all of whom served as privates in the 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Battalion, and Corporal Harry Prager, who served in Company H, 2nd Tennessee Infantry.[8]

Clifford Henderson’s Burial. Courtesy of Gettysburg National Military Park.

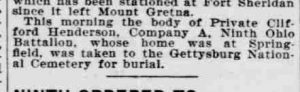

Hartwig identifies the picture (featured right) as the burial of Clifford Henderson.[9] I found additional information about this story in various newspapers from the period. According to a September 7, 1898 report in Cleveland, “Private Clifford Henderson, Company A. Ninth Ohio (colored) battalion, died of typhoid fever this morning in the Red Cross hospital. His body was sent home to Cleveland for burial.”[10] However, by September 9, the Philadelphia Inquirer was reporting that “this morning the body of Private Clifford Henderson, Company A, Ninth Ohio Battalion, whose home was at Springfield, [OH], was taken to the Gettysburg National Cemetery for burial.”[11]

Clifford Henderson died in 1898. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

While there is little other information regarding these soldiers or the particular motivations for burying them in the Civil War section of the national cemetery, Find a Grave has solid entries on Gooden, Prager, Henderson, Martin, and Farrell that show pictures of their grave markers and explain the exact placement of their burial locations. [12] Prager was from Tennessee and served with a unit from his home state, but for some reason, he was buried in the Illinois section.[13] I was also able to find

Charles Young. Courtesy of the National Park Service and the US Army.

some interesting information on the 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Battalion, in which three of the soldiers served. This was the unit headed by Col. Charles Young, a famous nineteenth century African American leader. He attended West Point, becoming only the third black graduate of the military academy and later served as the first black U.S. National Park Superintendent. [14] According to a book by Brian G. Shellum, the 9th Ohio battalion was in the nation’s press quite a bit during the Spanish-American conflict for “its superior discipline and training.” However, the battalion also experienced low morale, especially after their time at Camp Meade, the place where all three soldiers died before being buried at Gettysburg.[15]

The story of the final black veteran buried at Gettysburg is even stranger in some ways than the ones that brought Gooden or Prager and his 1898 peers to the cemetery. Steve Light’s 2012 blog post “Forgotten Valor – The Lincoln Cemetery” and James M. Paradis’s African Americans and the Gettysburg Campaign (2013) help explain how Civil War veteran Charles H. Parker arrived at the cemetery in 1936.[16] Charles H. Parker served in Company F of the 3rd United States Colored Troops. [17] Upon his death on July 2, 1876, he was buried in the Yellow Hill Cemetery, which became essentially abandoned. [18] Parker’s grave was rediscovered as a part of a restoration project and then reinterred at Gettysburg.[19]

Why these decisions to integrate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery? The newspaper record is almost completely silent. Hartwig argues that the four Spanish American War soldiers were buried there because it was the closest National Cemetery.[20] The men had been stationed at Camp Meade in Middletown, Pennsylvania, so the Gettysburg National Cemetery was just under 50 miles away. Margaret S. Creighton’s The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s Forgotten History (2005) argues that segregation within national cemeteries was a major issue for African Americans. She claims that local veteran Lloyd Watts, an African American sergeant during the Civil War, and the “Sons of Good Will,” a black fraternal society he co-created, fought for integration at the various local cemeteries. While

Headstone for Charles Parker. Courtesy of the House Divided Research Engine.

African Americans were permitted to partake in the burials of white soldiers, white soldiers often refused to assist in and attend black soldiers’ burials. Creighton suggests that there was local segregation between the black and white communities in Adams County throughout the 1880s and 1890s. [21] However, the timing of Gooden’s burial in 1884 points to the beginning of the end of this segregation regime at least in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery . As historian John R. Neff argues in Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation (2005), the burial of black soldiers in national cemeteries established them as “the first publicly funded integrated cemeteries in American history.”[22]

Neff assumes that Gooden’s burial was intentional, designed to insure that the “the color line of segregation…was between blue and gray, not black and white.”[23] Yet the odd stories of the scattered six black burials at Gettysburg and the near total lack of commentary on these developments in the national press, raise questions about this assumption. Does anyone have more detail, or new theories about how to interpret the halting story of integration at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery? Feel free to comment below and we will update this post as more information becomes available.

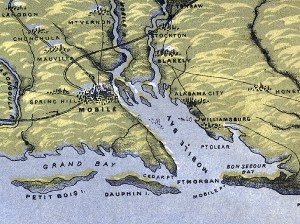

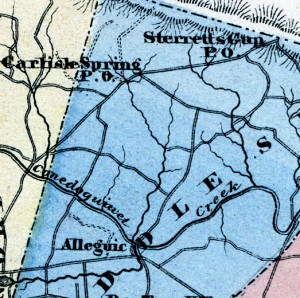

Map showing burial sites of black veterans at Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg (Adapted by Becca Stout)d

Endnotes

[1] James Oakes, “The Emancipation Proclamation,” Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013), 378, 387.

[2] Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin, Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013), 291-293. [Google Books]

[3] D. Scott Hartwig, “A Burial in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery,” The Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park, April 2012. [WEB]

[4] Brenna McKelvey, “Henry Gooden,” House Divided Research Engine. [WEB]

[5] D. Scott Hartwig, “A Burial in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery,”

[6] Gettys Bern, “PVT. Henry Gooden,” Find a Grave, August 8, 2006. [WEB]

[7] Brandie Kessler, “Did Union soldier’s family move body away from black soldier’s grave?” Evening Sun, November 19, 2013. [WEB]

[8] D. Scott Hartwig, “A Burial in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery,”

[9] D. Scott Hartwig, “A Burial in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery,”

[10] Brian G. Shellum, “Volunteer Officer in the Spanish-American War,” Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment: The Military Career of Charles Young (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010). [Google Books]

[11] “Governor’s Day at Camp Meade,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, (September 9, 1898), 5. [Newspapers.com Proquest]

[12] Karl Stelly, “CPL Harry S. Prager (1860-1898),” Find A Grave Memorial, August 23, 2009. [WEB]

[13] Karl Stelly, “PVT Emmert Martin (Unknown-1898),” Find A Grave Memorial, November 3, 2010. [WEB]; Karl Stelly, “PVT Clifford Henderson (Unknown-1898),” Find A Grave Memorial November 3, 2010. [WEB]; Karl Stelly, “PVT Nicholas Farrell (Unknown-1898),” Find A Grave Memorial, November 3, 2010. [WEB]

[14] “Colonel Charles Young,” National Park Service, May 21, 2018.

[15] Brian G. Shellum, “Volunteer Officer in the Spanish-American War,”

[16] Steve Light, “Forgotten Valor – The Lincoln Cemetery,” Battlefield Back Stories, September 29, 2012. [WEB]; James M Paradis, African Americans and the Gettysburg Campaign (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2013), 107-109. [Google Books]

[17] Don Sailer, “Charles H. Parker,” House Divided Research Engine. [WEB]

[18] Steve Light, “Forgotten Valor – The Lincoln Cemetery,” Battlefield Back Stories, September 29, 2012. [WEB]

[19] Savannah Labbe, “Separate but Equal? Gettysburg’s Lincoln Cemetery,” The Gettysburg Compiler: On the Front Lines of History, March 12, 2018. [WEB]

[20] D. Scott Hartwig, “A Burial in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery,”

[21] Margaret S. Creighton, The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s Forgotten History (New York: Basic Books, 2005), 217-218.

[22] John R. Neff, Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005), 133.

[23] John R. Neff, Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation, 134.

Additional Readings

Primary Source Documents

The Emancipation Proclamation

The Militia Act of July 1862

Secondary Source Documents

Gettysburg General Reading

United States Colored Troops

Ninth Ohio Battalion

Second Tennessee Infantry