While previous posts have discussed political cartoons from American publications like Harpers Weekly, Punch was a popular periodical in England. Art Historian Allan T. Kohl works at Minneapolis College of Art & Design and has put together an interesting collection of Punch’s “principal cartoons” related to the Civil War. Weekly editions “featured a principal cartoon, sometimes called the “big cut,” commenting on a significant event or issue,” as Kohl explains. Each cartoon includes a short description and one can browse this collection in several different ways. In addition, Kohl discusses the various ways that historic individuals and national symbols appeared in the cartoons. The chief illustrator at Punch during this period was John Tenniel (1820-1914) , who also provided the illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1872). You can learn more about Tenniel in Frankie Morris, Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel (2005). Both Google Books (1862) and the Internet Archive (June-Dec. 1860) have digitized some issues of Punch from this period.

30

Aug

10

Civil War Political Cartoons

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Images Themes: Contests & Elections, US & the World24

Aug

10

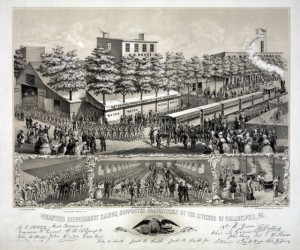

Refreshment Saloons in Civil War Philadelphia

Posted by mckelveb Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Images, Recent Scholarship Themes: Business & IndustryHouse Divided is in the process of adding interactive essays to the database as a part of its Journal Divided project. I created an essay on the Philadelphia refreshment saloons that specifically focused on the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon and its contribution to the city’s home front relief efforts during the Civil War. The Cooper Shop opened on May 26, 1861 and went on to add a hospital in October that cared for sick and wounded soldiers throughout the duration of the war. Although larger refreshment saloons formed in the city, Philadelphia’s residents warmly remembered the Cooper Shop because of the dramatic individual efforts of its three leaders: William M. Cooper, the president of the establishment, Dr. Andrew Nebinger, the head surgeon of the Cooper Shop Hospital, and Anna M. Ross, the Lady Principle of the hospital. Visiting physicians such as Dr. C.E. Hill described the positive atmosphere created by the committee’s hospitality and claimed, “soldiers were never better cared for than in this hall.” The refreshment saloons are still remembered in modern scholarship as historian J. Matthew Gallman commented, the saloons “greatest benevolent contribution cannot be measured by returns on ledger sheets, but by the long hours devoted to sewing clothes, cooking food, and ministering to wounded soldiers.” The saloons closed in late August 1865 as the war came to an end and they were no longer needed.

For more interactive essays, visit the Journal Divided Site. Click on any of the images below to view a slide show of the Philadelphia Volunteer Refreshment Saloons during the Civil War in Flickr.

30

Jul

10

Confederate raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania (October 1862)

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals, Images, Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & Soldiers Before going to bed on October 10, 1862, Chambersburg resident William Heyser noted in his diary that he had “secreted some of my most valuable papers.” Confederate cavalry under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart had arrived several hours earlier and forced the town to surrender. Union forces had been caught by surprise and none were available to defend the town. “It would have been an act of madness to have made resistance…and would have involved the total destruction of the town,” as the Chambersburg (PA) Valley Spirit noted. The raid, as the Milwaukee (WI) Sentienel described, “was the most daring adventure of the war” so far. Besides gathering intelligence, one of the Confederate’s other objectives was to take as many supplies as possible. Horses were one key item and Alexander Kelly McClure, an assistant adjutant Union general, later recalled how ten horses were taken from his farm. (You can read McClure’s full account of the Confederate raid – “A Night With Stuart’s Raiders”- here). Yet as one Confederate soldier’s letter revealed, they also seized a number of other supplies. “I got 8 pair of boots, 4 over coats, 5 pair of pantaloons, 2 hats, 6 pair of socks, 6 pr. Draws, 6 over & under shirts, [and] some coffe & sugar” during the raid, as Edward Cottrell told his grandmother. As Confederates left Chambersburg on October 11, they burned warehouses that held government supplies. One contained ammunition and, as Heyser described, “the succeeding explosions of shells and power was tremendous.” While Union forces were dispatched to intercept and capture the raiders, General Stuart evaded them and returned to Virginia without any major engagements. You can read more about the raid in Emory M. Thomas’ Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (1986) and Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (2008).

Before going to bed on October 10, 1862, Chambersburg resident William Heyser noted in his diary that he had “secreted some of my most valuable papers.” Confederate cavalry under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart had arrived several hours earlier and forced the town to surrender. Union forces had been caught by surprise and none were available to defend the town. “It would have been an act of madness to have made resistance…and would have involved the total destruction of the town,” as the Chambersburg (PA) Valley Spirit noted. The raid, as the Milwaukee (WI) Sentienel described, “was the most daring adventure of the war” so far. Besides gathering intelligence, one of the Confederate’s other objectives was to take as many supplies as possible. Horses were one key item and Alexander Kelly McClure, an assistant adjutant Union general, later recalled how ten horses were taken from his farm. (You can read McClure’s full account of the Confederate raid – “A Night With Stuart’s Raiders”- here). Yet as one Confederate soldier’s letter revealed, they also seized a number of other supplies. “I got 8 pair of boots, 4 over coats, 5 pair of pantaloons, 2 hats, 6 pair of socks, 6 pr. Draws, 6 over & under shirts, [and] some coffe & sugar” during the raid, as Edward Cottrell told his grandmother. As Confederates left Chambersburg on October 11, they burned warehouses that held government supplies. One contained ammunition and, as Heyser described, “the succeeding explosions of shells and power was tremendous.” While Union forces were dispatched to intercept and capture the raiders, General Stuart evaded them and returned to Virginia without any major engagements. You can read more about the raid in Emory M. Thomas’ Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (1986) and Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (2008).

28

Jul

10

Partisan Fear-mongering in 1860

Posted by Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Images After what could only be mildly described as a tumultuous decade of failed compromises, the rise of a new political party, and a disgruntled citizenry, the 1860 Election season met with the pronounced fears over the future course of the United States. Partisan newspapers relished the opportunity to hack away at their opponents by castigating their political views and theorizing on pressing social fears within the South. The Chicago Press and Tribune noted that the “slave breeders” of the South feared a Republican party in their midst that could claim Founders as part of its political pedigree. The article also cites an undated piece from the New Orleans Courier which speculated that if Republicans proved victorious in the upcoming election, Southerners would have to openly embrace the patronage positions offered them as members of a new Southern Republican “nucleus.” (Ironically, Lincoln and his cabinet maintained their hope in a latent Southern Unionism in Virginia that would dissuade the Upper South from seceding.) Other fears for the upcoming election literally struck at the belly of the South. Again, the Chicago Press and Tribune stated that a “poor corn-crop” would precede a potential famine in the upcoming year. Instead of stoking this fear in their hearts, Southerners could remain “patriots and good citizens’ by “behaving themselves” in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election. However, the Press and Tribune cynically mused that the “dissolution” of the Union would only be averted until the South had a “full crop.” Articles in partisan papers such as the Chicago Press and Tribune reveal the broad spectrum of fears endemic to the United States in the months leading up to the Election of 1860.

After what could only be mildly described as a tumultuous decade of failed compromises, the rise of a new political party, and a disgruntled citizenry, the 1860 Election season met with the pronounced fears over the future course of the United States. Partisan newspapers relished the opportunity to hack away at their opponents by castigating their political views and theorizing on pressing social fears within the South. The Chicago Press and Tribune noted that the “slave breeders” of the South feared a Republican party in their midst that could claim Founders as part of its political pedigree. The article also cites an undated piece from the New Orleans Courier which speculated that if Republicans proved victorious in the upcoming election, Southerners would have to openly embrace the patronage positions offered them as members of a new Southern Republican “nucleus.” (Ironically, Lincoln and his cabinet maintained their hope in a latent Southern Unionism in Virginia that would dissuade the Upper South from seceding.) Other fears for the upcoming election literally struck at the belly of the South. Again, the Chicago Press and Tribune stated that a “poor corn-crop” would precede a potential famine in the upcoming year. Instead of stoking this fear in their hearts, Southerners could remain “patriots and good citizens’ by “behaving themselves” in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election. However, the Press and Tribune cynically mused that the “dissolution” of the Union would only be averted until the South had a “full crop.” Articles in partisan papers such as the Chicago Press and Tribune reveal the broad spectrum of fears endemic to the United States in the months leading up to the Election of 1860.

26

Jul

10

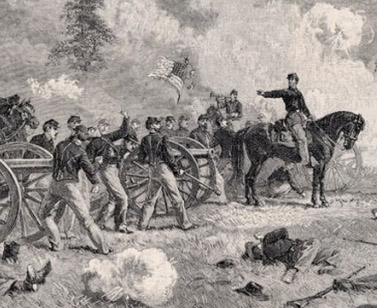

An Angry Father At Gettysburg

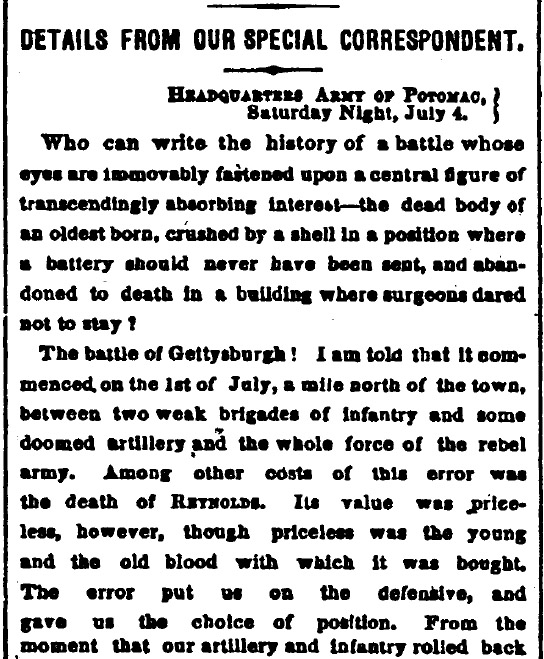

Posted by Matthew Pinsker Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals, Images Themes: Battles & Soldiers Sam Wilkeson was a war correspondent for the New York Times who had sons in the Union army, including Lt. Bayard Wilkeson, an artillery officer who was mortally wounded on the first day at Gettysburg. The story of Bayard’s death became a northern sensation since he was one of the youngest artillery officers in the army, the son of a prominent journalist and also because he died in a particularly heroic fashion. The young lieutenant covered the retreating forces from the Union XI Corps on the battle’s first day and reportedly had to amputate his own shattered leg when doctors were forced to flee in the face of the oncoming Confederates. The elder Wilkeson, who was married to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s sister, recovered his mangled son’s body in Gettysburg’s aftermath and wrote an angry report in the Times which appeared on July 6. The article began: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest –the dead body of an oldest born son, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay.” Unionists later redistributed the moving piece as a pamphlet under the title: Samuel Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture Of Gettysburgh. Artist Alfred Waud also drew a famous sketch of the young Wilkeson directing his battery on the battlefield. The story remains one of the most compelling of the battle. You can read more about it here at a special blog site built by Civil War enthusiast Randy Chadwick. Also, Louis M. Starr’s Bohemian Brigade: Civil War Newsmen in Action (1954) provides good context and more detail about Sam Wilkeson, one of the nation’s first embedded war correspondents. A more recent study by Michael A. Dreese, Torn Families: Death and Kinship at the Battle of Gettysburg (2007), provides several descriptive pages (available through Google Books) as part of a fascinating chapter on fathers and sons during the war.

Sam Wilkeson was a war correspondent for the New York Times who had sons in the Union army, including Lt. Bayard Wilkeson, an artillery officer who was mortally wounded on the first day at Gettysburg. The story of Bayard’s death became a northern sensation since he was one of the youngest artillery officers in the army, the son of a prominent journalist and also because he died in a particularly heroic fashion. The young lieutenant covered the retreating forces from the Union XI Corps on the battle’s first day and reportedly had to amputate his own shattered leg when doctors were forced to flee in the face of the oncoming Confederates. The elder Wilkeson, who was married to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s sister, recovered his mangled son’s body in Gettysburg’s aftermath and wrote an angry report in the Times which appeared on July 6. The article began: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest –the dead body of an oldest born son, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay.” Unionists later redistributed the moving piece as a pamphlet under the title: Samuel Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture Of Gettysburgh. Artist Alfred Waud also drew a famous sketch of the young Wilkeson directing his battery on the battlefield. The story remains one of the most compelling of the battle. You can read more about it here at a special blog site built by Civil War enthusiast Randy Chadwick. Also, Louis M. Starr’s Bohemian Brigade: Civil War Newsmen in Action (1954) provides good context and more detail about Sam Wilkeson, one of the nation’s first embedded war correspondents. A more recent study by Michael A. Dreese, Torn Families: Death and Kinship at the Battle of Gettysburg (2007), provides several descriptive pages (available through Google Books) as part of a fascinating chapter on fathers and sons during the war.

To view a slideshow in Flickr, click on any of the images below:

20

Jul

10

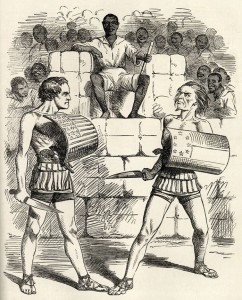

An Antebellum Gladiator

Posted by hardyr Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images Themes: Education & Culture, Slavery & Abolition The most popular American play of the antebellum period was the historical melodrama The Gladiator (1831), by the Philadelphia physician-turned-playwright Robert Montgomery Bird (1806-1854). Bird wrote the play, but actor Edwin Forrest owned it—literally. Bird sold Forrest (1806-1872) the rights to the play for $100, and Forrest performed the title role of Spartacus to sold-out houses at least a thousand times between 1831 the end of his career four decades later.

The most popular American play of the antebellum period was the historical melodrama The Gladiator (1831), by the Philadelphia physician-turned-playwright Robert Montgomery Bird (1806-1854). Bird wrote the play, but actor Edwin Forrest owned it—literally. Bird sold Forrest (1806-1872) the rights to the play for $100, and Forrest performed the title role of Spartacus to sold-out houses at least a thousand times between 1831 the end of his career four decades later.

When he saw Forrest in the role of Spartacus in 1846, Walt Whitman wrote that the play was “as full of ‘Abolitionism’ as an egg is of meat.” Whitman continued: “It is founded on that passage of Roman history where the slaves—Gallic, Spanish, Thracian and African—rose against their masters, and formed themselves into a military organization, and for a time successfully resisted the forces sent to quell them. Running o’er with sentiments of liberty—with eloquent disclaimers of the right of the Romans to hold human beings in bondage—it is a play, this ‘Gladiator,’ calculated to make the hearts of the masses swell responsively to all those nobler manlier aspirations in behalf of mortal freedom!”

But Bird, the playwright, was no abolitionist. He was afraid of the violence abolitionism would bring down upon the nation. In his 1836 novel Sheppard Lee, for example, he portrays the institution of slavery as essentially benign, and his fictional slaves as content with their servitude until stirred to insurrection by an abolitionist pamphlet. The spectre of a slave uprising haunted him.

The Gladiator was first performed in April 1831, five months before an actual slave rebellion, under the leadership of Nat Turner, erupted in Virginia. As the news of the rebellion reached Bird, he wrote in his diary: “At this present moment there are 6[00] or 800 armed negroes marching through Southampton County, Va. murdering, ravishing & burning those whom the Grace of God has made their owners—70 killed, principally women & children. If they had but a Spartacus among them—to organize the half million of Virginia, the hundreds of thousands of the other States and to lead them on in the Crusade of Massacre, what a blessed example might they not give to the world of the excellence of slavery! What a field of interest to the playwrites of posterity! Someday we shall have it; and future generations will perhaps remember the horrors of Hayti as a farce compared with the tragedies of our own unhappy land! The vis et amor sceleratus habendi [force and criminal love of gain] will be repaid, violence with violence, & avarice with blood…”

Meanwhile, Edwin Forrest continued to pack houses with his portrayal of Spartacus. And in 1860, Matthew Brady produced a series of photographs of Forrest in costume for his most popular roles, including Spartacus. The National Portrait Gallery has a web exhibit of Brady’s photographs of Forrest. Fellow photographer Marcus Aurelius Root called them Brady’s “most remarkable productions…for artistic effect.”

20

Jul

10

Battle of Nashville: December 15-16, 1864

Posted by mckelveb Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Images, Maps, Places to Visit, Recent Scholarship Themes: Battles & Soldiers The Battle of Nashville took place on December 15-16, 1864 in Davidson County, Tennessee as a part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. Beginning in November 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood led the Army of Tennessee towards Nashville in a last attempt to move Union Major General William T. Sherman out of Georgia. By December 1, 1864 Union Major General George H. Thomas and his forces reached Nashville and spent the next two weeks preparing for battle. The fighting began in the morning on December 15 with most of the Union assaults on the Confederates ending successfully. The following day, the Union troops charged the Confederate forces and made them abandon Nashville and retreat across the Tennessee River. The Civil War Preservation Trust’s website offers an article: “The Decisive Battle of Nashville” that provides an overview of the fighting. The website also includes a map that depicts troop movements on both sides as well as brief biographies of General Hood and General Thomas. Also, the Battle of Nashville Preservation Society website offers historic sites and photographs related to the battle. Some other resources that may be useful are the Memoir of Major General George H. Thomas and John Bell Hood’s Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate Armies which could provide contrasting views from commanding officers in both the Union and Confederate Armies to give different perspectives of the battle. Richard M. McMurry commented on the Battle of Nashville in his book:

The Battle of Nashville took place on December 15-16, 1864 in Davidson County, Tennessee as a part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. Beginning in November 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood led the Army of Tennessee towards Nashville in a last attempt to move Union Major General William T. Sherman out of Georgia. By December 1, 1864 Union Major General George H. Thomas and his forces reached Nashville and spent the next two weeks preparing for battle. The fighting began in the morning on December 15 with most of the Union assaults on the Confederates ending successfully. The following day, the Union troops charged the Confederate forces and made them abandon Nashville and retreat across the Tennessee River. The Civil War Preservation Trust’s website offers an article: “The Decisive Battle of Nashville” that provides an overview of the fighting. The website also includes a map that depicts troop movements on both sides as well as brief biographies of General Hood and General Thomas. Also, the Battle of Nashville Preservation Society website offers historic sites and photographs related to the battle. Some other resources that may be useful are the Memoir of Major General George H. Thomas and John Bell Hood’s Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate Armies which could provide contrasting views from commanding officers in both the Union and Confederate Armies to give different perspectives of the battle. Richard M. McMurry commented on the Battle of Nashville in his book:

“Late that rainy day, as Hood was conferring with Stewart, the Yankee’s swarmed over Shy’s Hill, annihilating the defenders and sending the remnants of Cheatham’s corps flying off in mad panic. The rout spread to Stewart’s corps. Only Lee’s men preserved a semblance of order, as most of the army dissolved and fled southward in darkness and rain. Hood and other officers tried desperately to rally the fleeing soldiers, but, save for a brave, defiant few who turned to fire at the Federals, their efforts were in vain. Over the fast thawing ground and through sticky mud, the Confederates made their way southward, while Lee strung his corps across the rear of the army to slow the Yankee pursuit. All that night Hood’s men jammed the roads southward from Nashville, abandoning wagons and cannons, throwing away muskets, swords, knapsacks, and camp equipment.”

20

Jul

10

“An Heir to the Throne,” 1860 political cartoon

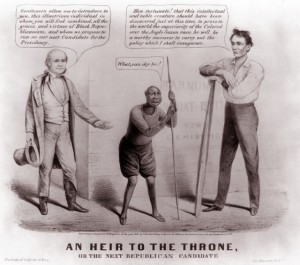

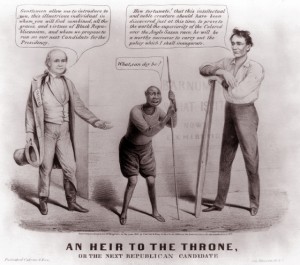

Posted by solnitr Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images Themes: Contests & Elections “An Heir to the Throne, or the Next Republican Candidate” satirizes the Republican Party’s stand on slavery in the 1860 presidential election. Democrats attacked Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party for rejecting the expansion of slavery into new territories. Louis Maurer, the artist of this 1860 Currier & Ives cartoon, depicted the ultimate allegiance between the Republicans and African-Americans, as Horace Greeley (on the left) introduced the black man in the center of the cartoon as the Republican Party’s “next Candidate for the Presidency.” Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, came out in favor of Lincoln during the May 1860 Democratic convention in Chicago and used his position in the press to advocate for Lincoln leading up to the election. In the cartoon, Lincoln’s response flouted any convention of race at the time, by declaring that his party’s new candidate will “prove to the world the superiority of the Colored over the Anglo Saxon race.”

“An Heir to the Throne, or the Next Republican Candidate” satirizes the Republican Party’s stand on slavery in the 1860 presidential election. Democrats attacked Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party for rejecting the expansion of slavery into new territories. Louis Maurer, the artist of this 1860 Currier & Ives cartoon, depicted the ultimate allegiance between the Republicans and African-Americans, as Horace Greeley (on the left) introduced the black man in the center of the cartoon as the Republican Party’s “next Candidate for the Presidency.” Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, came out in favor of Lincoln during the May 1860 Democratic convention in Chicago and used his position in the press to advocate for Lincoln leading up to the election. In the cartoon, Lincoln’s response flouted any convention of race at the time, by declaring that his party’s new candidate will “prove to the world the superiority of the Colored over the Anglo Saxon race.”

Though the caricature of Lincoln made what would have been, an outrageous statement on the hierarchy of the races, the subject of his assertion—the black man—was still labeled as a “creature.” Maurer actually borrowed this image of a black man from P.T. Barnum’s American Museum exhibit “What is it?” Barnum advertised the exhibit, which ran in New York in 1860, as the link between human beings and monkeys. An announcement that ran in the March 1, 1860 edition of the New York Tribune attempted to draw in spectators with the attention-grabbing questions: “Is it a lower order of man? or is it a higher development of the monkey? or Is it both in combination?” The question of race, and of slavery, was on the forefront of Americans’ minds in 1860, adding to the relevance of Barnum’s exhibit. In addition, Charles Darwin published his ground-breaking scientific work, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection: Or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, only months before on November 24, 1859 in London.

19

Jul

10

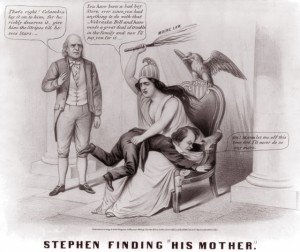

“Stephen Finding His Mother” 1860 Political Cartoon

Posted by rothenbb Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images, Recent Scholarship Themes: Contests & Elections Louis Maurer mocked presidential candidate Stephen Douglas in the cartoon “Stephen Finding His Mother.” Through the months leading up to the election in late 1860, Douglas engaged in an unprecedented national campaign tour. In response to critics of his new vote-gathering methods, he falsely claimed to visit his mother when he lead his tour through New York and New England. Using this story as the basis for the cartoon, Maurer shows Columbia as Douglas’ “mother” who, at the urging of Uncle Sam, punishes him for dividing Democrats and bringing scorn from Republicans. She uses a branch labeled the “Maine Law,” a possible reference to Maine’s 1851 temperance law, to “give him the Stripes till he sees Stars.”

Louis Maurer mocked presidential candidate Stephen Douglas in the cartoon “Stephen Finding His Mother.” Through the months leading up to the election in late 1860, Douglas engaged in an unprecedented national campaign tour. In response to critics of his new vote-gathering methods, he falsely claimed to visit his mother when he lead his tour through New York and New England. Using this story as the basis for the cartoon, Maurer shows Columbia as Douglas’ “mother” who, at the urging of Uncle Sam, punishes him for dividing Democrats and bringing scorn from Republicans. She uses a branch labeled the “Maine Law,” a possible reference to Maine’s 1851 temperance law, to “give him the Stripes till he sees Stars.”

By 1860 Stephen Douglas had encountered criticism despite his great achievements in Congress. Maurer’s cartoon, though immediately drawing from Douglas’ “mother” story, connected with other issues. Douglas had begun alienating himself from Southern Democrats as an opponent to the extension of slavery. Critics also cited his close association with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which determined the extension of slavery based on a state’s majority vote. Though the Act promised the success of this “popular sovereignty” within Kansas and Nebraska, it soon backfired and brought even more tension and violence to the states.

Robert W. Johannsen wrote a leading biography entitled Stephen A. Douglas. The book, available for partial view on Google Books, provides closer analyses of Douglas through the campaign of 1860.

19

Jul

10

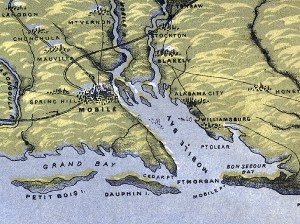

Battle of Mobile Bay: August 2-23, 1864

Posted by mckelveb Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Images, Lesson Plans, Maps, Places to Visit, Recent Scholarship Themes: Battles & SoldiersThe Battle of Mobile Bay (also known as the Passing of Forts Morgan and Gaines) took place from August 2-23, 1864 in Mobile and Baldwin Counties, Alabama. In early August, a large Union fleet under the command of Admiral David G. Farragut entered Mobile Bay and came under fire from Confederate forces. Farragut led his forces past the forts and forced Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan to surrender. On August 23, Fort Morgan was the last place to fall and Mobile Bay’s port closed. The Civil War Preservation Trust’s website offers an article, “Damn the Torpedoes: The Battle of Mobile Bay,” which provides a detailed summary of the battle and its commanding officers. The website also includes a map that depicts the movement of Union and Confederate forces as well as a list of recommended readings for more information on Mobile Bay. The National Park Service’s website includes a lesson plan on Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay that includes images, readings, and maps. Foxhall Alexander Parker commented on Farragut as he and his forces crossed into Mobile Bay:

“As they were passing the Brooklyn, her captain reported ‘a heavy line of torpedoes across the channel.’ ‘Damn the torpedoes!’ was the emphatic reply of Farragut. ‘Jouett, full speed! Four bells, Captain Drayton.’ And the Hartford, as if eager to bear the admiral’s flag to the front, bounded forward ‘like a thing of life,’ and, increasing her speed at each instant, crossed both lines of torpedoes, going over the ground at the rate of nine miles an hour; for so far had she drifted to the northward and westward while her engines were stopped, as if to make it impossible for the admiral, without heading directly on to Fort Morgan, to obey his own instructions to ‘pass eastward of the easternmost buoy.’”

Another resource that may be useful is West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay, available as a preview on Google Books, which provides a detailed overview of the Battle of Mobile Bay and its significance during the Civil War. Also available on Google Books is By Sea and By River: The Naval History of the Civil War which includes details on the battle as well as the aftermath and consequences of Mobile Bay. The Civil War Trail’s website has information for those planning on visiting the battle site for a field trip as well as details on the different stops within the area and historic sites close by.