While phones can be a distraction in the classroom, with augmented reality (AR) they can help bring lessons to life and create an interactive learning experience. By simply aiming their phones at augmented images, students can unlock the personal stories of historical figures, triggering videos and other online content (called auras). Here at the House Divided Studio, we are working to enhance our visitor experience and to model classroom applications through the use of AR. You can learn more about the various uses of AR and how to create your own free augmented experiences in this instructional post.

Downloading the HP Reveal app

To view the auras created by the House Divided Project, visitors and educators can download the free HP Reveal app, create an account and follow the House Divided channel in HP Reveal. (House Divided content won’t trigger until you follow the channel). Once those steps are completed, simply open the app, select the blue viewer square located at the bottom of the screen, point your phone at images located throughout the studio and the app generates specific video content (auras) related to those images.

Once you’ve followed the House Divided channel on the HP Reveal app, select the blue viewer button and then point your phone at an image.

Using Augmented Reality

Through AR, teachers can bring new experiences into their classrooms. Below are some of the most innovative uses of AR.

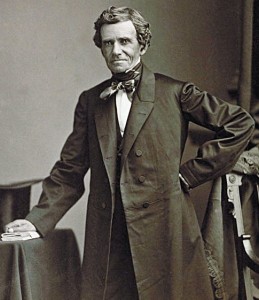

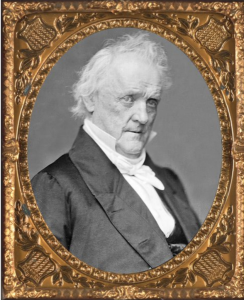

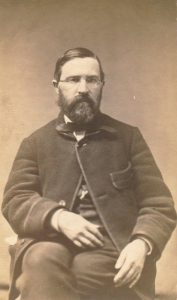

- Augmented Portraits – At the House Divided studio, the walls are decorated with augmented portraits that trigger brief student-produced films. At right, check out this augmented portrait of President James Buchanan (Class of 1809). You can access all of the House Divided images with AR enhancements here at the online version of our studio.

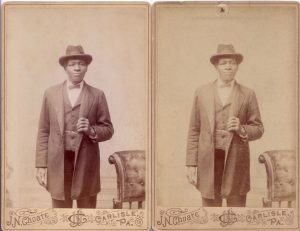

- Handouts/Facsimiles – Reproductions of historic photos, letters and newspaper articles enable students to connect to personal stories. Here’s an example of Lincoln’s famous Blind Memorandum from the 1864 election, augmented with a video by project director Matthew Pinsker.

- Virtual field trips – The Google Expeditions app is already being used in schools. Google created a brief promotional video showing how students at an Iowa middle school experienced world-renowned architecture using the app. The app is free, and can be downloaded and accessed by anyone with a Google account. Google Expeditions shows virtual images of sites accompanied by longer text explanations, available by tapping the bottom of your screen. Especially in classroom settings, Google encourages the use of a Virtual Reality headset for the best experience. Students can place their phones into the headsets, known as Google Cardboard, and experience a site. The Cardboard headsets are available for around $15.

Creating Your Own Augmented Reality Experience

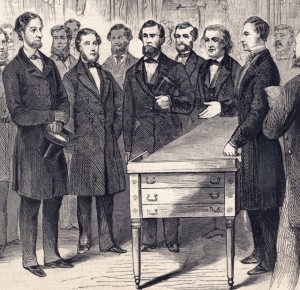

Augmented reality is not only an effective teaching tool, but it is also free and relatively easy to learn. Using the HP Reveal studio, you can upload images and augment them. When editing your image, you should use a variety of circles, eclipses and rectangles to mask the background of your image (see below), making faces and main objects easier for the app to recognize.

Tips for masking images:

- Identify and mask mundane objects/spaces in the background of your image. Think of it as removing clutter so the app can recognize the image and trigger your content. For the example above, I masked the indistinct faces of the pursuers in the background, making it easier for the app to focus on the four main figures.

- HP Reveal is often color sensitive. If your trigger image is in color, a black and white version (i.e., photocopies) may not work successfully. For the best results, convert an image to grayscale and then mask it.

- Finally, make sure you save and then share your aura. If you haven’t shared your aura, it will be marked private.

After you have finished masking the image, click “Next” and upload your overlaying video or other content. Press save and then try viewing the image through the HP Reveal app to verify it works.

For more guidance on how to mask images in the HP Reveal studio, see the following House Divided tutorial.

![1865-04-14 Garrison [?] at Sumter](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/1865-04-14-Garrison-at-Sumter-163x300.png)

![Image 3 Garrison [?] standing center](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/Image-3-Garrison-standing-center-1024x638.png)